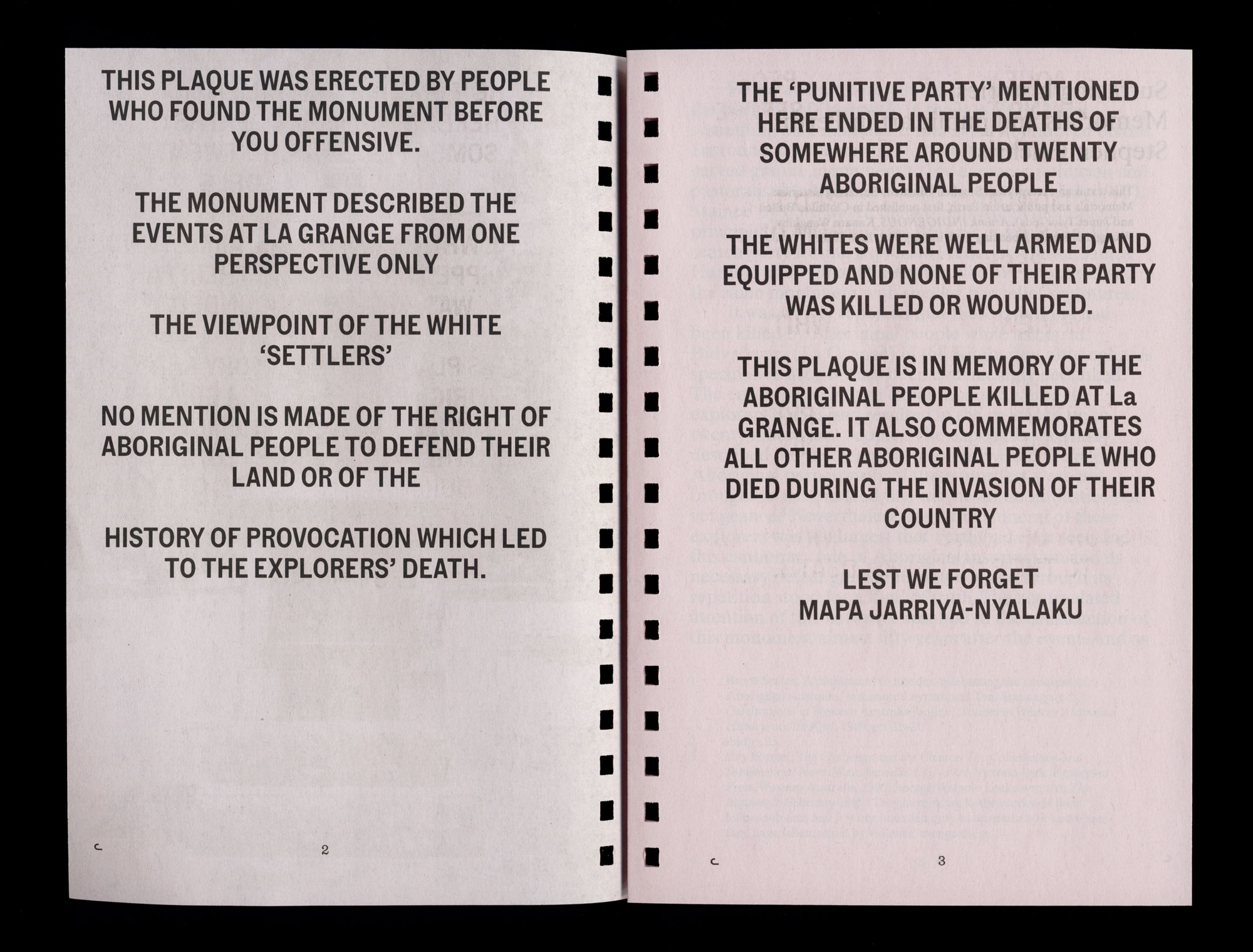

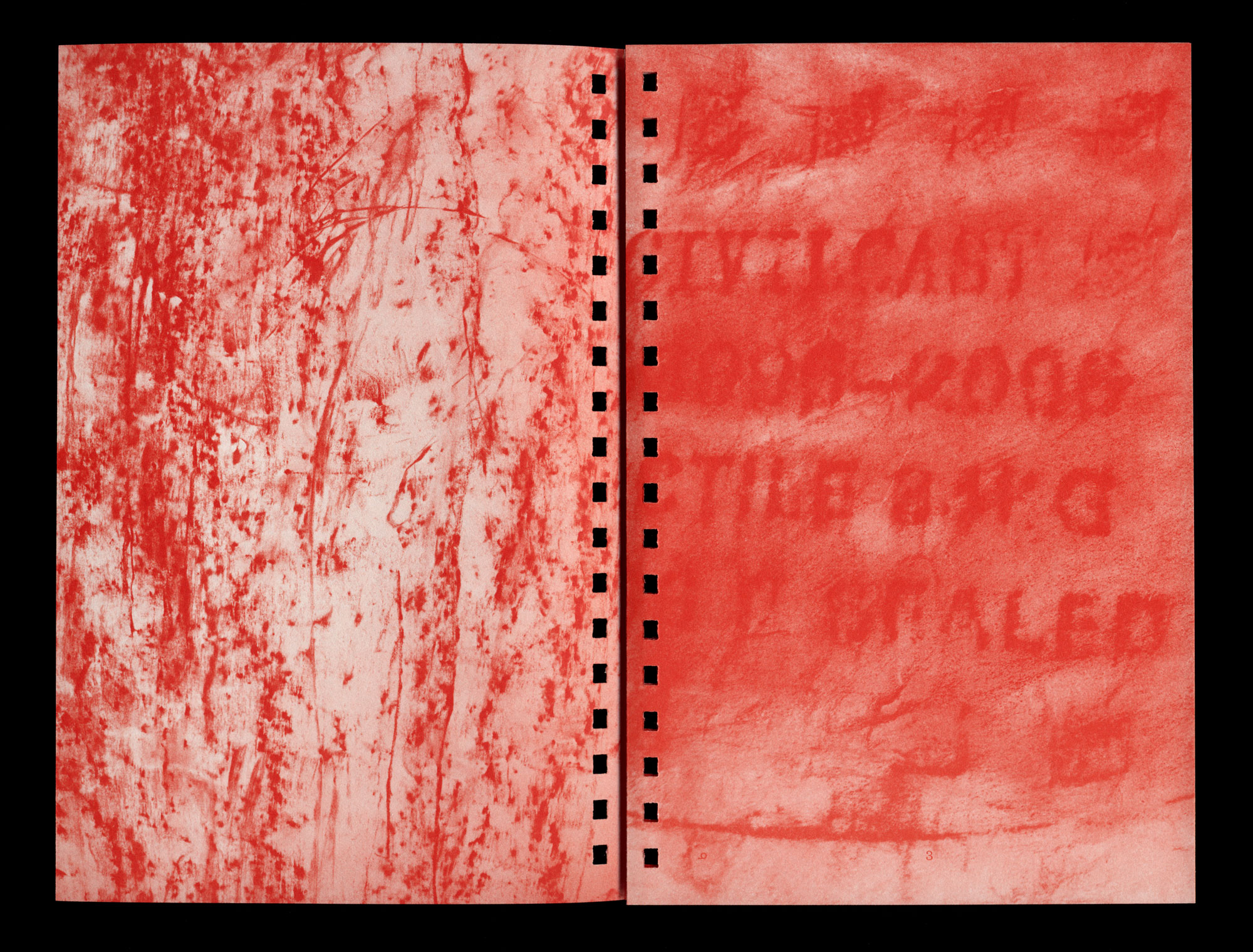

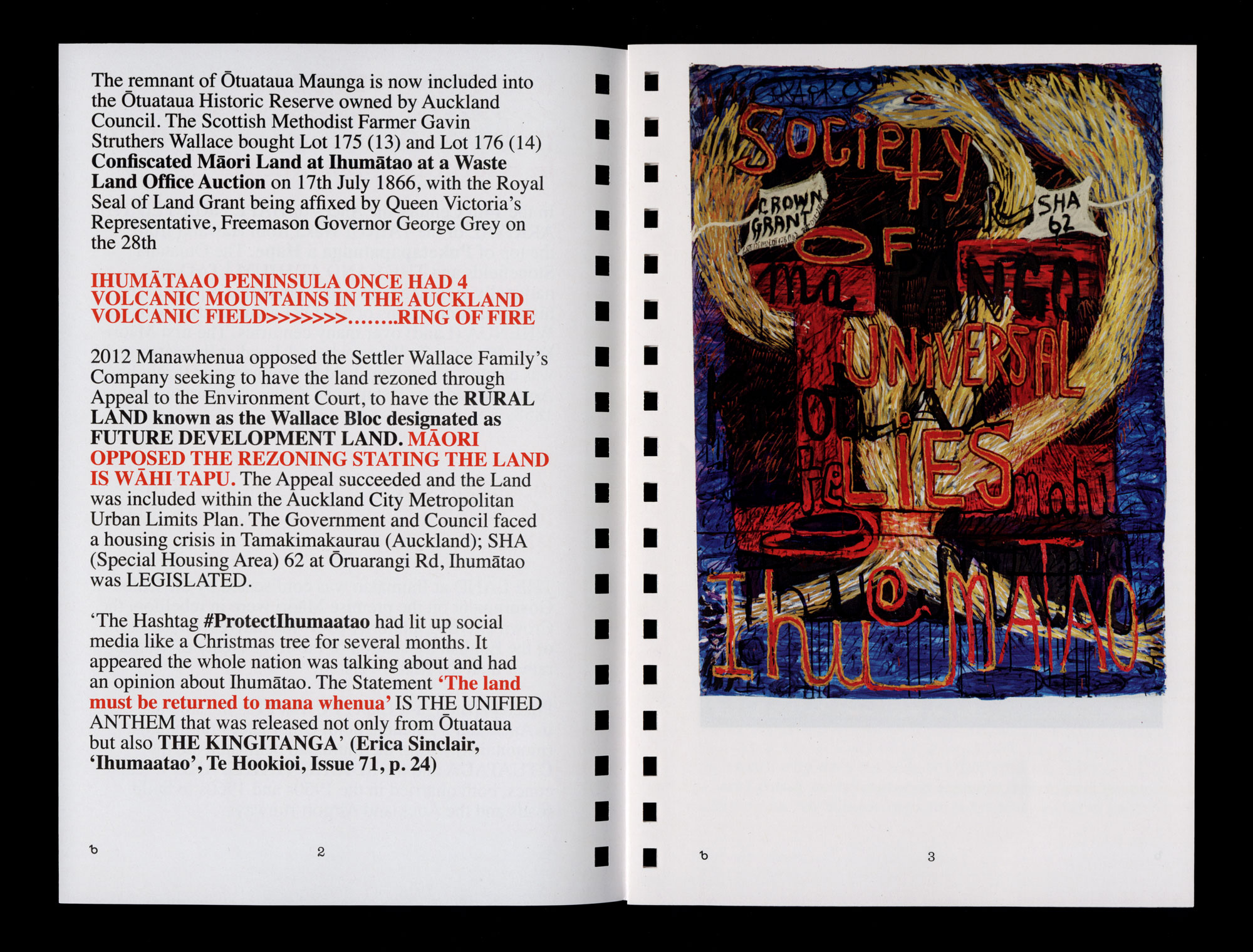

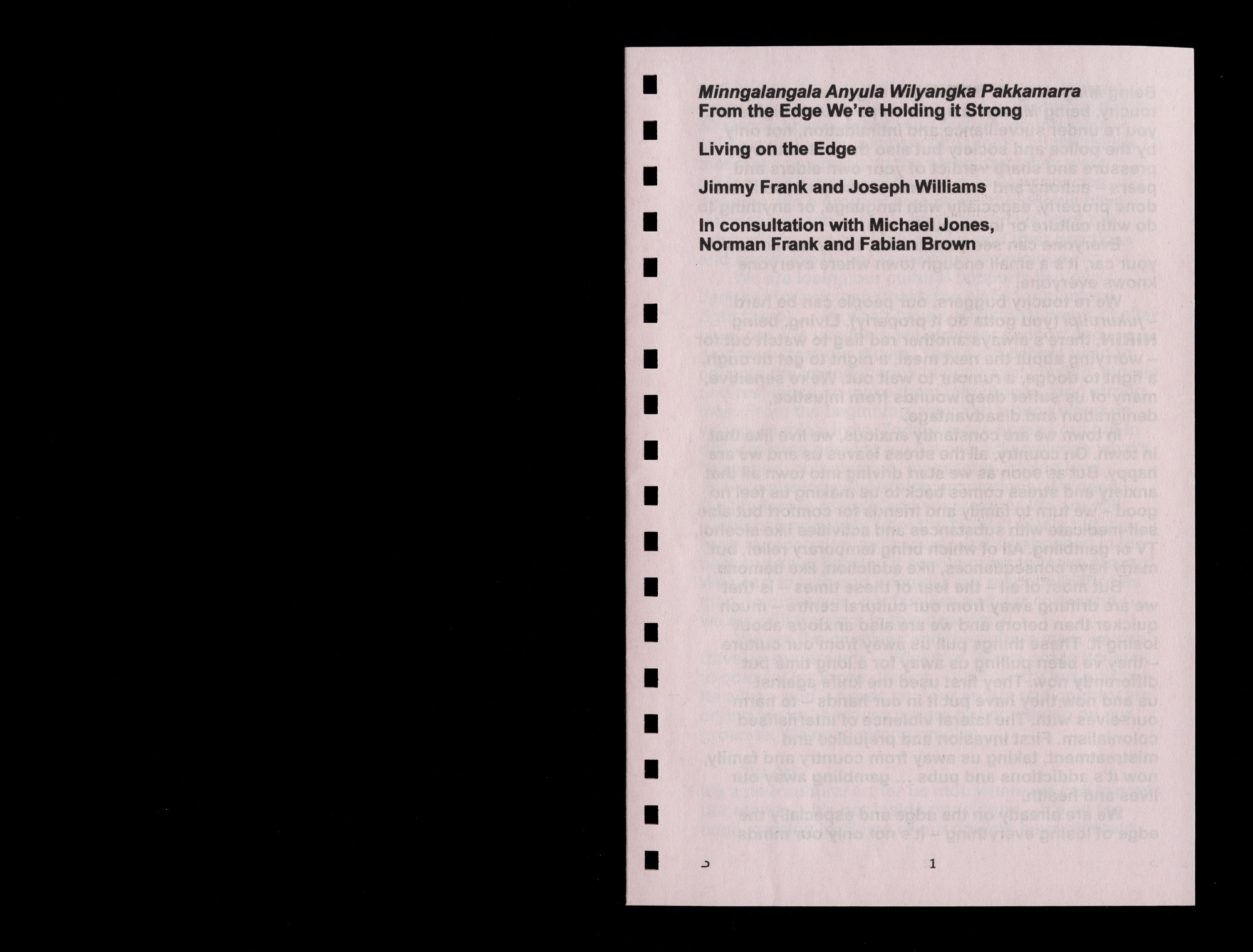

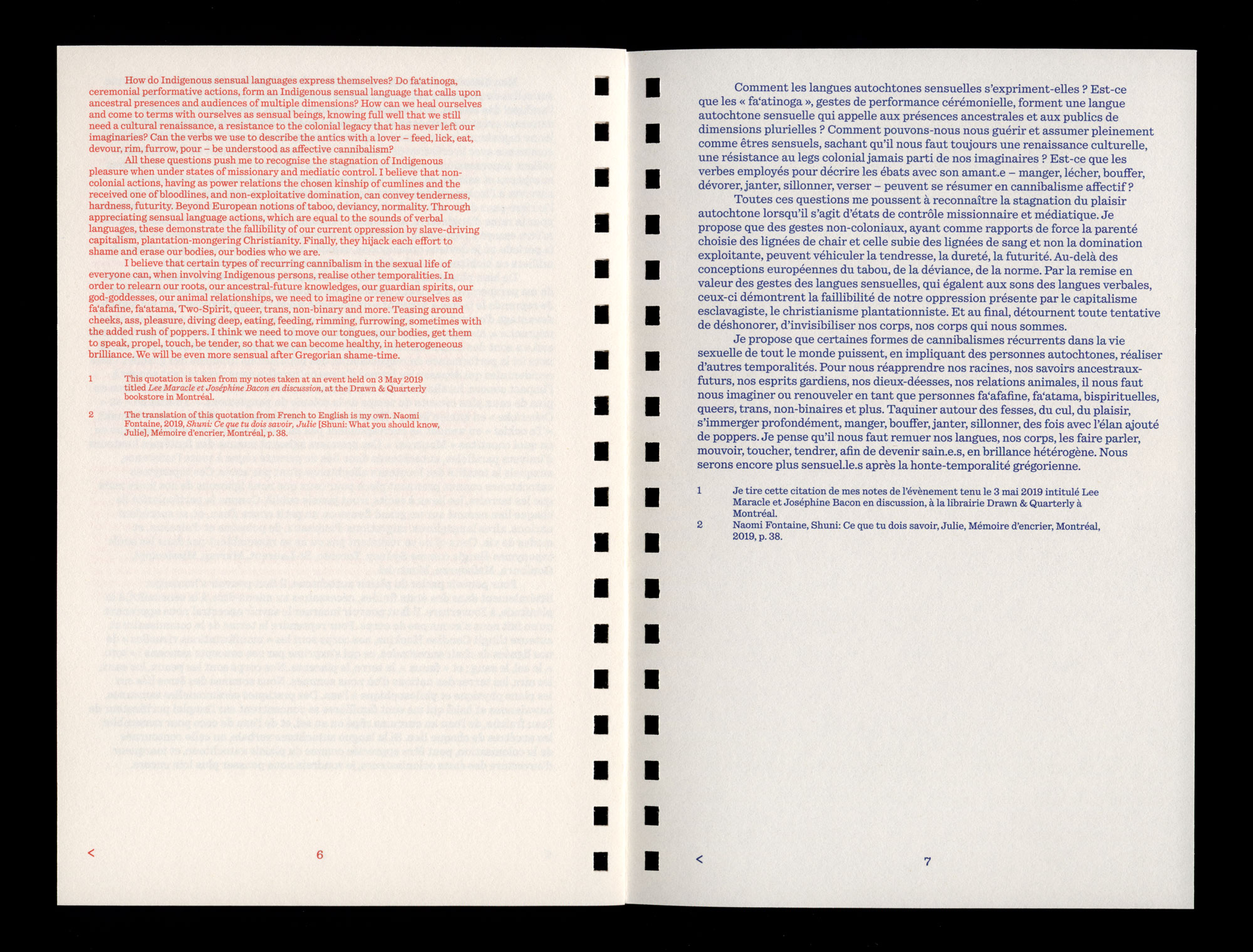

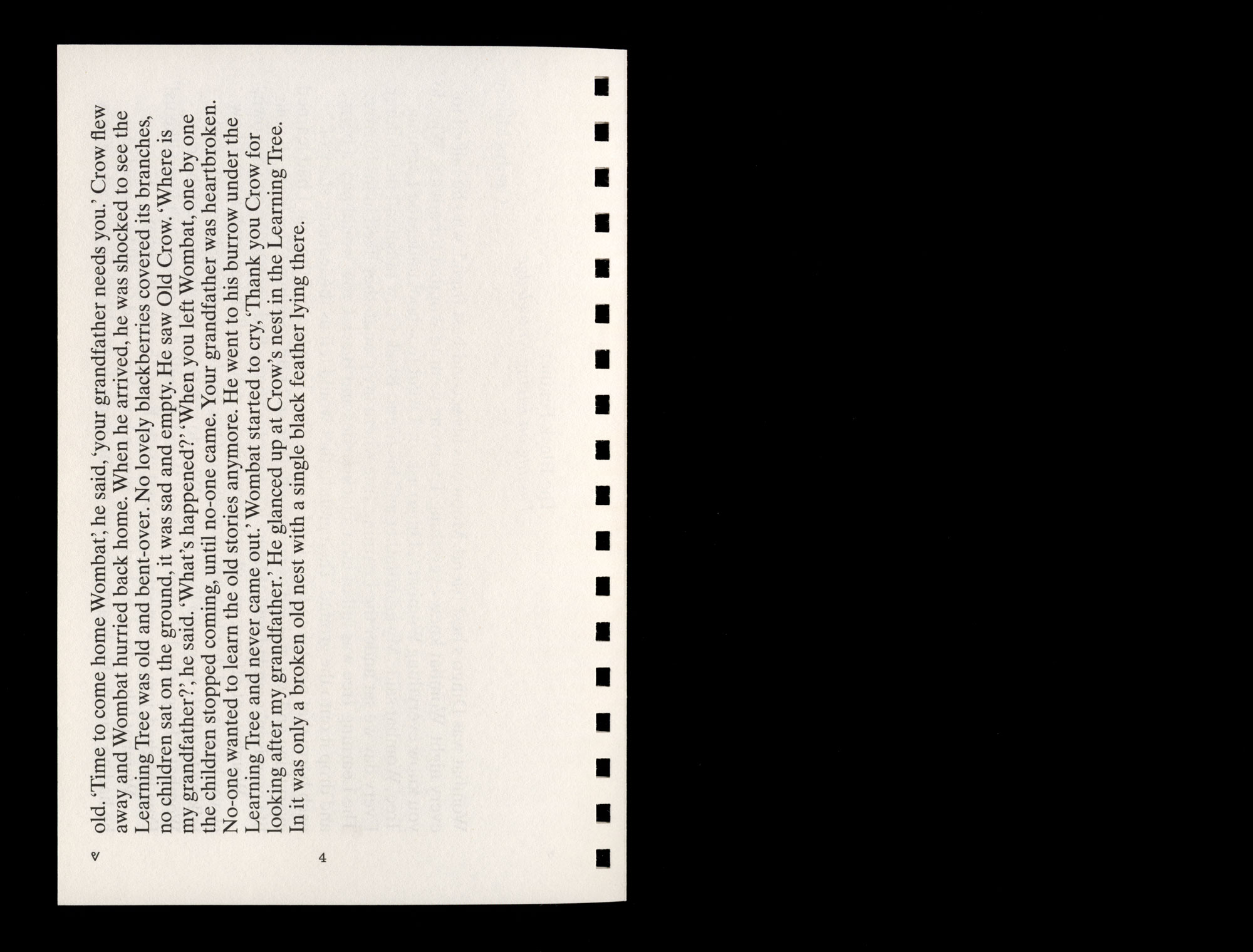

THIS PLAQUE WAS ERECTED BY PEOPLE

WHO FOUND THE MONUMENT BEFORE

YOU OFFENSIVE.

THE MONUMENT DESCRIBED THE

EVENTS AT LA GRANGE FROM ONE

PERSPECTIVE ONLY

THE VIEWPOINT OF THE WHITE

‘SETTLERS’

NO MENTION IS MADE OF THE RIGHT OF

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE TO DEFEND THEIR

LAND OR OF THE

HISTORY OF PROVOCATION WHICH LED

TO THE EXPLORERS’ DEATH.

THE ‘PUNITIVE PARTY’ MENTIONED

HERE ENDED IN THE DEATHS OF

SOMEWHERE AROUND TWENTY

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE

THE WHITES WERE WELL ARMED AND

EQUIPPED AND NONE OF THEIR PARTY

WAS KILLED OR WOUNDED.

THIS PLAQUE IS IN MEMORY OF THE

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE KILLED AT La

GRANGE. IT ALSO COMMEMORATES

ALL OTHER ABORIGINAL PEOPLE WHO

DIED DURING THE INVASION OF THEIR

COUNTRY

LEST WE FORGET

MAPA JARRIYA-NYALAKU

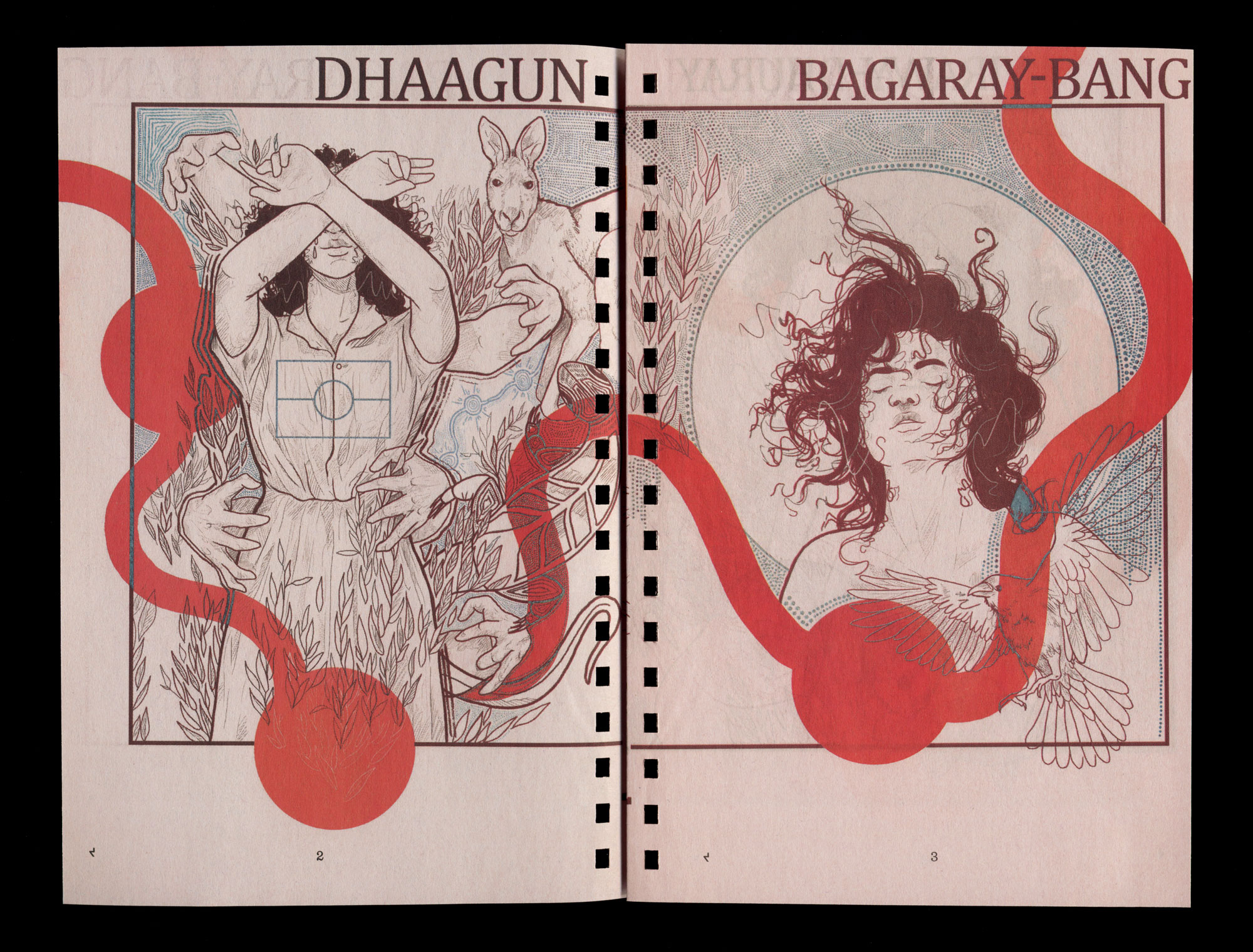

Surfacing histories:

Memorials and public art in Perth

This text is an excerpt from Stephen Gilchrist, ‘Surfacing histories: Memorials and public art in Perth’, first published in Clothilde Bullen and James Tylor (eds), Artlink INDIGENOUS, Kanarn Wangkiny Wanggandi Karlto [Speaking from inside], 38:2, June 2018.

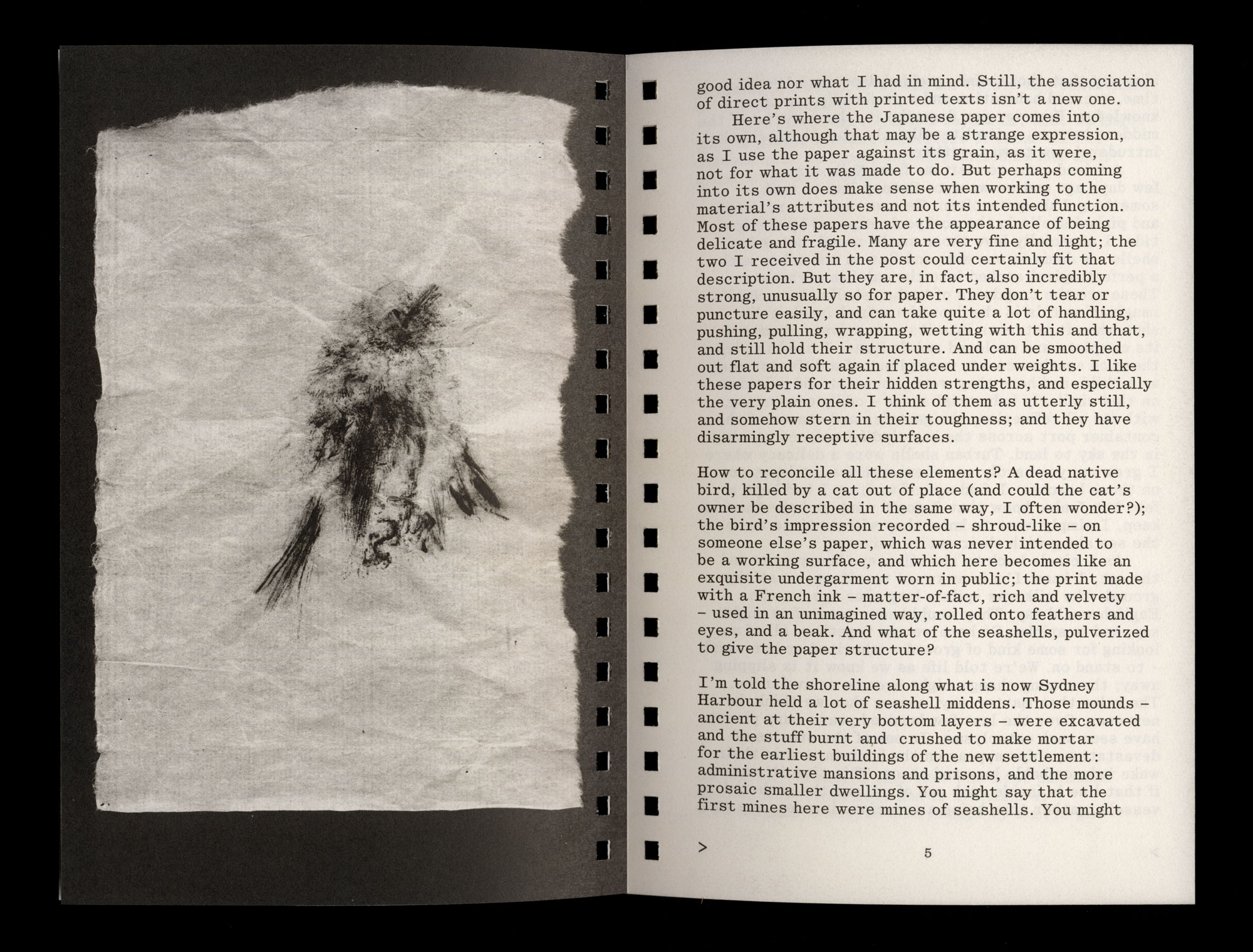

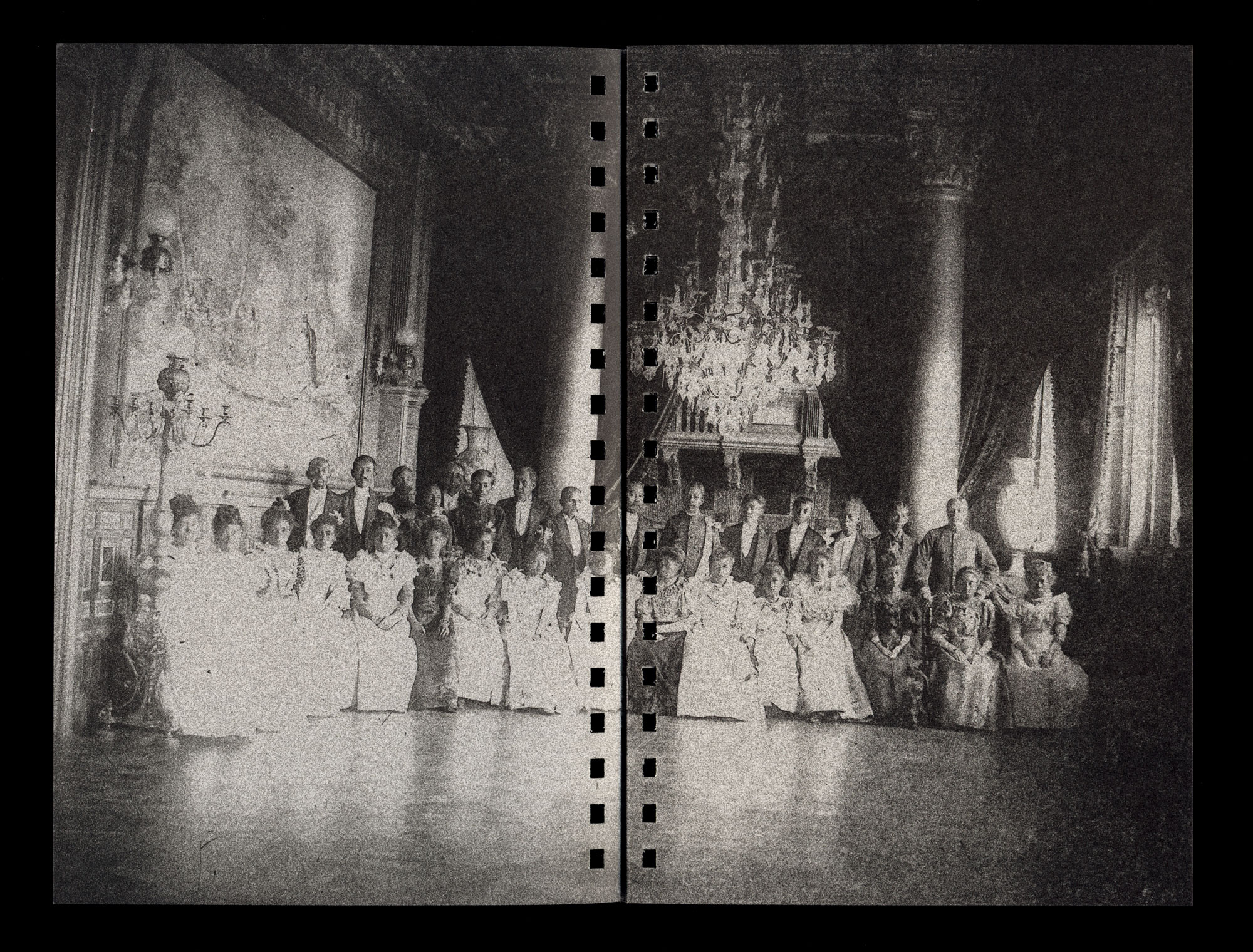

While walking through the Esplanade Park in the port city of Fremantle in the late 1990s, I saw something on a monument that I had not noticed before. Surrounded by towering Norfolk Island Pines is a carved granite monument to the explorer, politician and pastoralist Maitland Brown (17 July 1843 – 8 July 1905). Stained by bore water, the six-metre-high monument principally commemorates Brown’s command of a search party for the explorers Frederick Panter, James Harding and William Goldwyer who are memorialised in the same monument with smaller bas-relief sculptures.

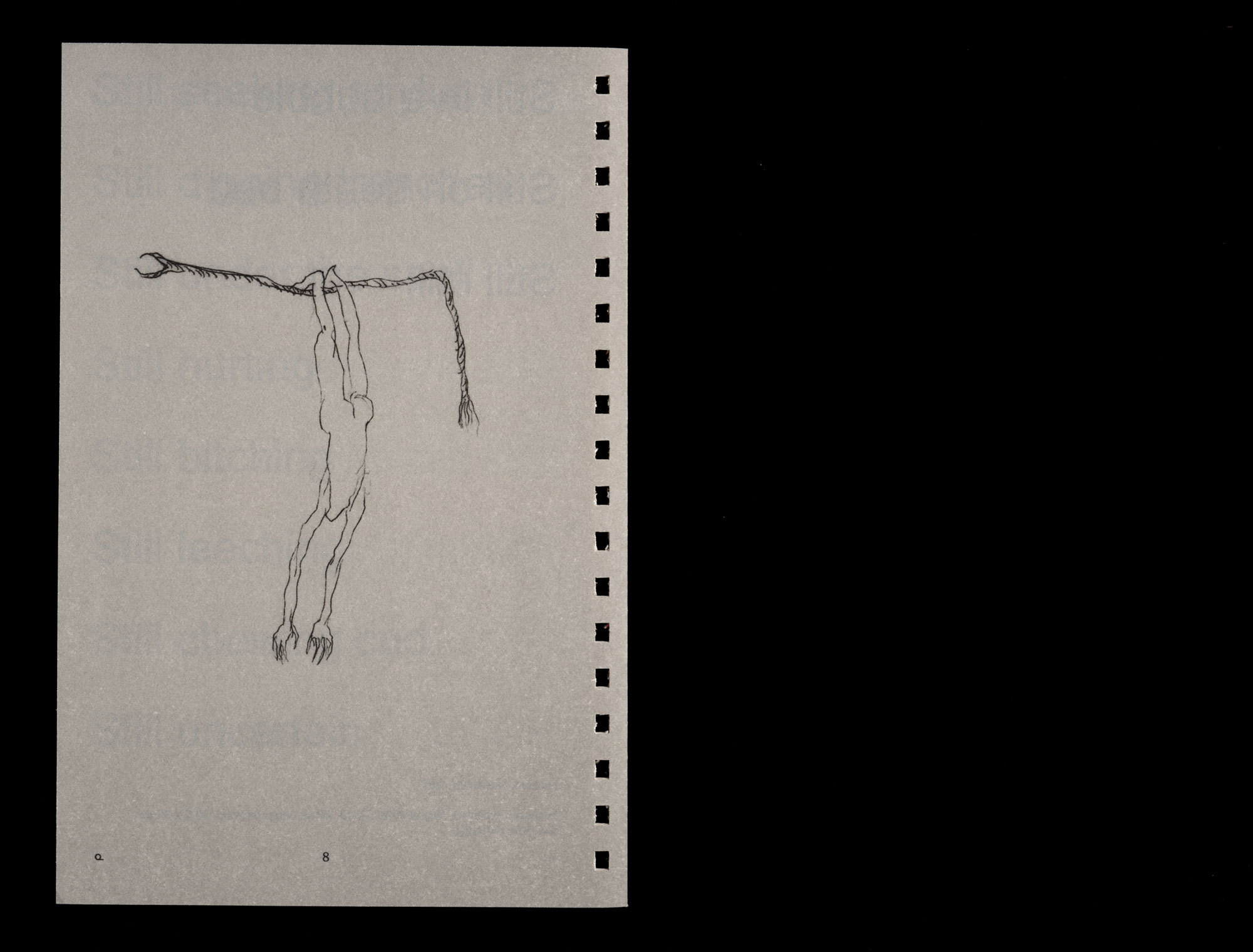

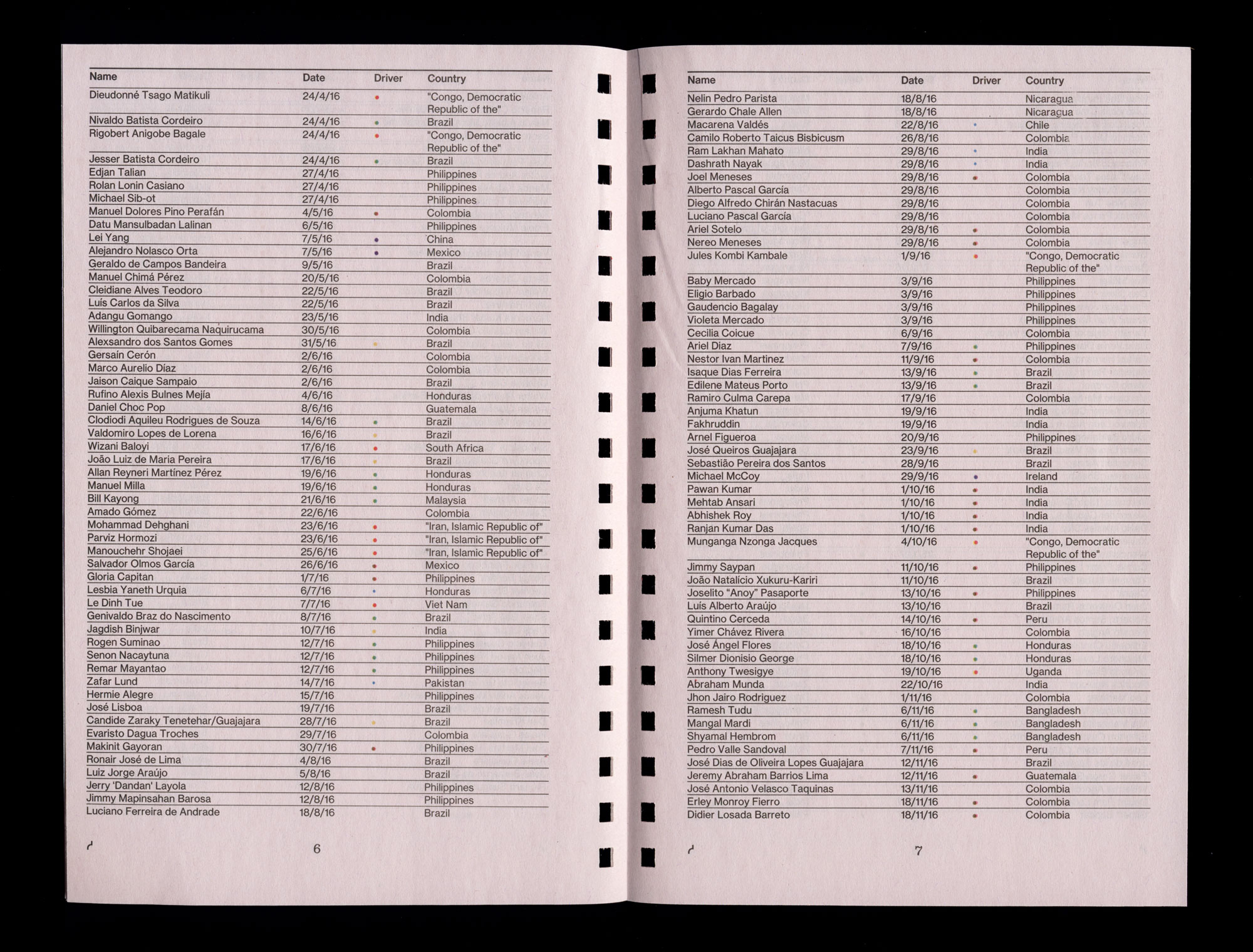

It was widely reported that these explorers had been killed by Aboriginal people while asleep at Bidyadanga (La Grange) in the Kimberley, although this speculative account has been convincingly debunked.1 The ensuing La Grange expedition recovered the explorers bodies and resulted in the deaths of up to twenty Aboriginal people.2 The expedition is grimly described on the memorial as punitive and the alleged Aboriginal perpetrators of these murders were not brought to trial, indeed this was never about justice but vengeance.3 Nevertheless, the public funeral of these explorers was the largest that Perth had ever seen and this cautionary tale of Aboriginal insurrection and its necessary defeat grew in its potency and through its repetition stood for a kind of truth. The accumulated attention of this narrative resulted in the construction of this monument almost fifty years after the event. And as history has shown us, for those who dominate the tools of dissemination, truth need only be the representation of it.

In the practiced way Indigenous people learn to filter out the dissonant messaging of these traumatic and re-traumatising histories, I barely even registered the memorial when I walked past it. But on this occasion, it was not the bronze bust of Maitland Brown that caught my attention, but the placement of a smaller plaque that had a slightly different patina and was sparring for space towards the base of the plinth. I learned that it had been added on the 9th of April 1994 by the Fremantle Aboriginal Baldja Network working with Historians Bruce Scates and Raelene Frances.

As a young history student, this small plaque was a revelation. It dared to publicly and permanently contradict the heroism and innocence of these settlers, and the expansionist fantasies of their journeys into “Terra incognita”. While I flinched at the one-dimensional nature of their narrative, I also recognised the importance of being a speaking subject within this history and speaking out to this history. The plaque served not only to interrogate the veracity of these particular historical claims, but also how these ideological markers still have a hold over our personal thinking and collective behaviour.

These attempts to place alternative and often oppositional versions of historical narrative side by side, is now understood to be an act of dialogical memorialisation4 and they generate expansionary movement in and produce less familiar versions of our histories. Jenny Gregory, president of the History Council of WA, suggests that local councils should routinely audit statues and plaques to check for offensive wording, saying “History and historical research doesn’t stand still.”5

It is significant that both plaques end with “Lest We Forget” which has entered into common usage across the Commonwealth as an invocation to never forget the human sacrifice of war. But in Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The Recessional”, from where the phrase is principally derived, the message is more nuanced and its sadness more allusive. Composed for and published towards the end of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 1897, the poem does extol aggressive British imperial power, but it also suggests that this earthly power – the “Dominion over palm and pine” – could be impermanent and finite. Indeed, the poem anticipates the declining years of the British Empire. The interventionist nature of this plaque signals not only the value of gathering the past into the present and lingering in the space of discomfort, but also a democratisation of history and a reimagining of what could come and what we could become together. While these corrective measures are important and offer a restorative process of cultural equity, whiteness is still central to the narrative. We need not just an audit of memorials, but the creation of new memories.

-

Bruce Scates, ‘A monument to murder: celebrating the conquest of Aboriginal Australia,’ in Lenore Layman and Tom Stannage (eds), Celebrations in Western Australia [online]. Studies in Western Australian History, no. 10, April 1989, pp. 21–31. ↩

-

ibid, p. 23. ↩

-

Kay Forrest, The Challenge and the Chance: The Colonisation and Settlement of North West Australia 1861–1914, Victoria Park, Hesperian Press, Western Australia, 1996. George Walpole Leake wrote in The Inquirer, 8 February 1865, ‘They have fallen in the service of their fellow‐subjects, and it is our bounden duty to ascertain how and where they have fallen: and if by violence, avenge them.’ ↩

-

Bradley Donald West, ‘Dialogical Memorialization, International Travel and the Public Sphere: A Cultural Sociology of Commemoration and Tourism at the First World War Gallipoli Battlefields’ in Tourist Studies, vol. 10, Issue 3, p. 210. ↩

-

Victoria Laurie, ‘Maitland Brown bust bears scars of when row came to a head’, The Australian, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/indigenous/maitland-brown-bust-bears-scars-of-when-row-came-to-a-head/news-story/67f07c0872abca49c9f7613bdb10384a accessed April 2018. ↩