My father’s mother had each of her children go out to the woods and choose a branch commiserate with their body size. This branch was transformed into a whip.

In her kitchen, near the stove, there was a row of nails. Each of her children had their personal whip hanging from the appropriate nail. She also carried a general long whip hanging from her waist. That one was used when she felt it necessary to restore order in her kitchen. That whip could reach all the corners and was used against all bodies.

She was of European descent. She was unsure of which part of Europe. She was extremely white – looking, very Slavic. Her husband was Indigenous and Black. He died of diabetes when my father was young.

My father’s father’s mother was Black and a photograph of her hung in the house. Slavery in Brazil ended in 1888 and she was born around 1870. Under the photo, my father’s mother’s white hand held the whip that met my father’s darker flesh.

Later, this photograph was thrown way – but the same aunt who did not want it in her house, ‘Because I never met the woman, Maria Alves’ (that is my great grandmother’s name, the Portuguese equivalent of Jane Smith) does have a family portrait of her husband’s family – at a great family gathering in Germany. She who never left Brazil, who has not met any of them because they were never in Brazil, and yet, keeps that photo in her kitchen. This aunt also nicknamed one of her daughters ‘Preta’ (the English equivalent of Negro as opposed to Black). She said, ‘because everything is Black about her daughter’. What she meant is everything is Indigenous looking about her daughter.

When my father’s mother met me in 1983, she raised her dress and showed me her upper thighs which the sun had not reached and exclaimed, ‘See, I am white.’ As she went through the photo album, she paused at relatives who were dark and said they were ugly. The relatives who were white she pointed out as beautiful.

My father’s mother says of her daughter-in-law, ‘she is Black but can wash clothes real clean.’

Her daughter-in-law is not Black, she is Indigenous. But it would be too much of an insult to call her Bugre.

(Bugre means an Indigenous person. It is the term that is used in this village and in some other areas of Brazil for Indigenous people. It is racist. The word is from the same use as ‘booger-man’).

The last known massacre of an Indigenous village in this area was in the 1930s. The white family that was involved (along with others) in this massacre still live in the community today. The cab driver from a nearby town who drove me to my aunt’s home in 2017 was from that family.

Last year I saw a video of Haitian Blacks involved in a ceremony where people are being whipped. Haiti, brave Haiti – who the USA and the world will forever make pay for daring to liberate herself from slavery. I had not understood, until then, about the concept of general whipping. There is whipping as punishment – such as when my father ‘did something wrong’ and thus he could prepare himself mentally for what was to come. But in this video, there is a man who uses his whip at everyone all the time – and they never know when and where it will hit their body.

And this can be soul-destroying because your mind and body must always be on the alert for the whipping.

My father’s best friend was called, Bugre. He said he was not a Bugre. My father was called Rouge, (Red).

My aunt’s (the one known as Black) second husband still speaks an Indigenous language. He is not sure which one. I ask, ‘who are his people?’. He said that he is not a Bugre. In referring to her beloved uncle’s desire to travel with me this aunt said, ‘Who would want an ugly Bugre?’

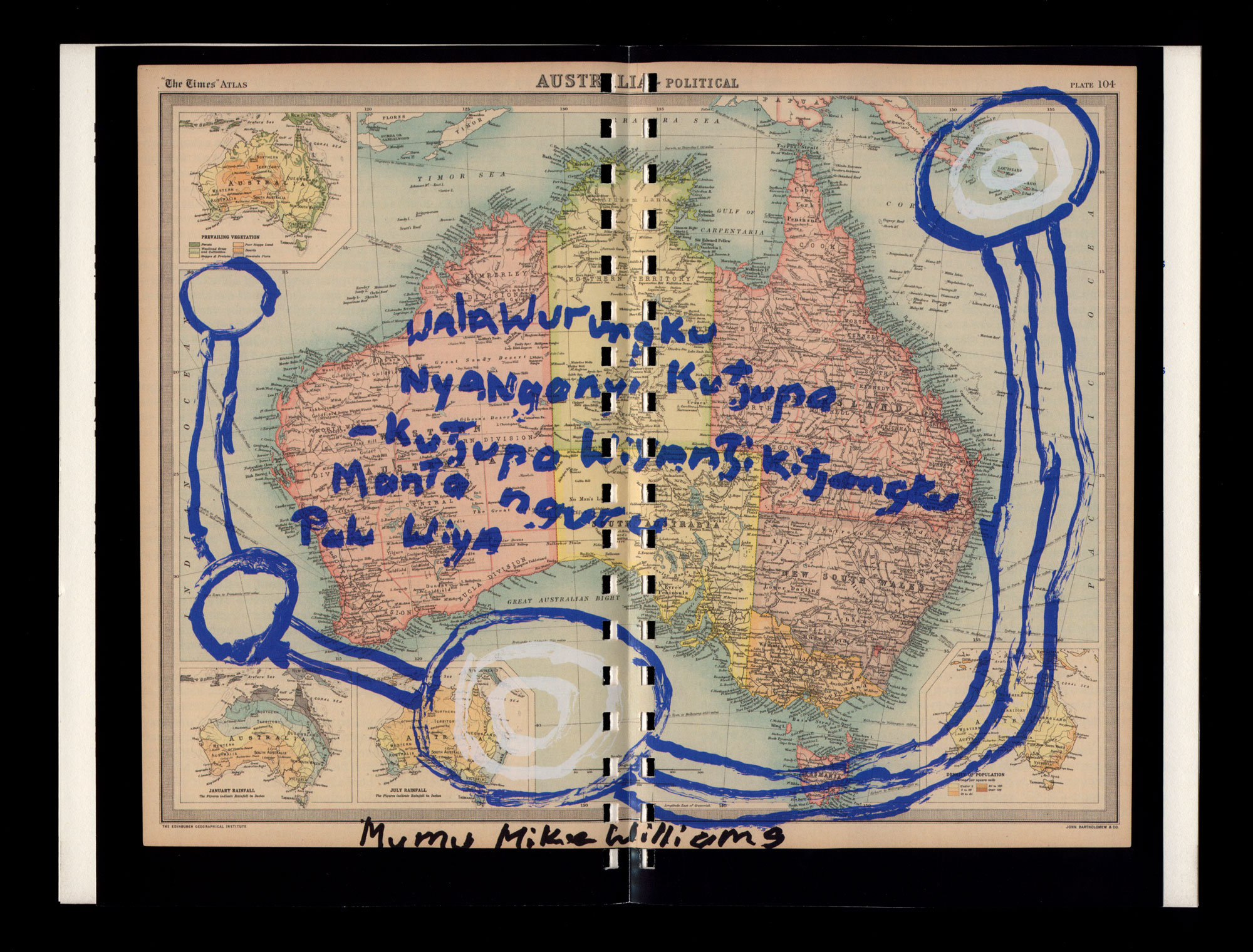

My father’s village is in the state of Parana, in southern Brazil.

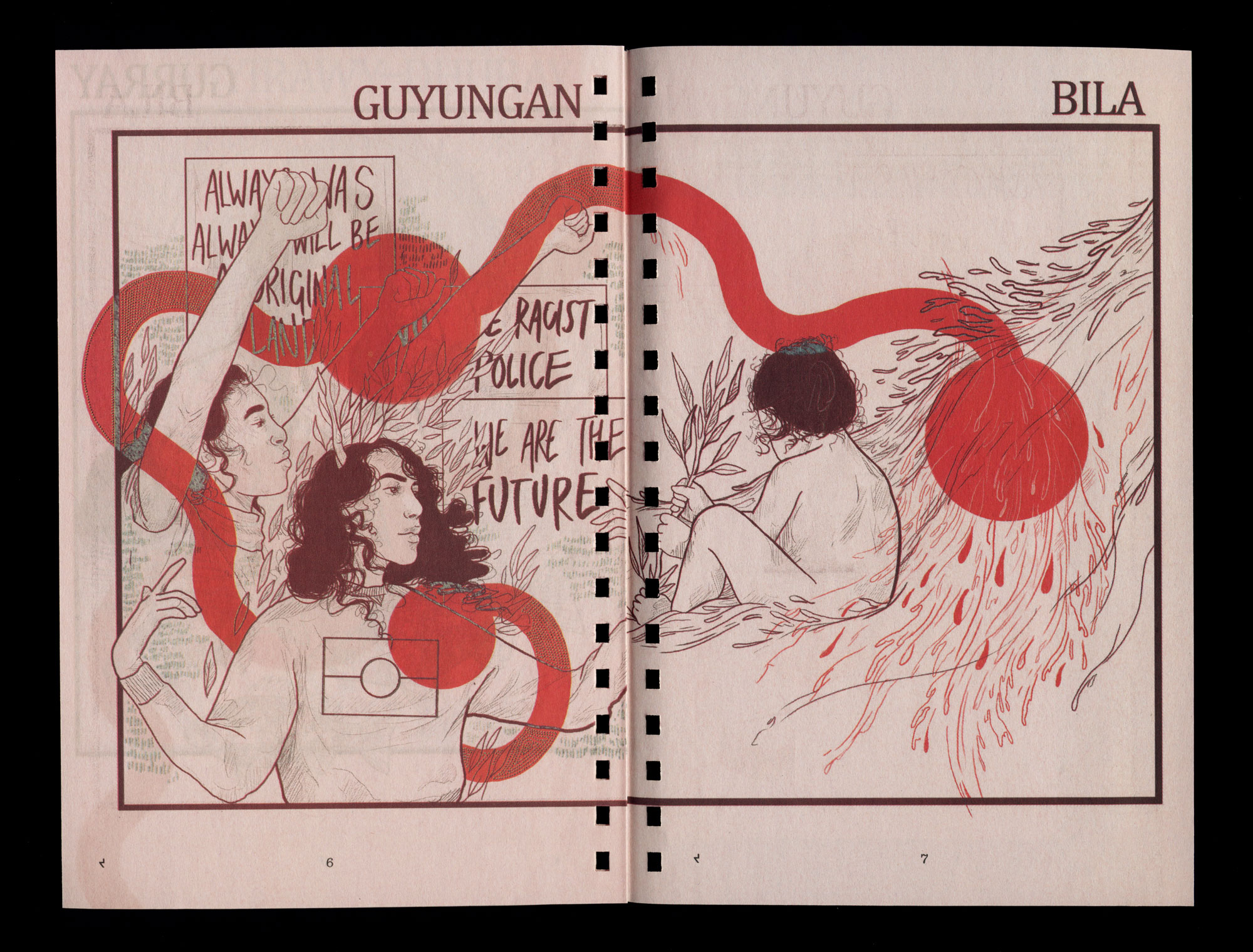

This area was a contested and defended Indigenous territory of the Kaingang, Xokleng, Xeta, and Guarani peoples. It was the land of huge, generous and graceful Araucaria pine trees. In the late 1800s, the army came on a genocidal campaign to remove Indigenous communities for the building of colonising railroads, such as the Brazil Railway Company, which would bring in white European settlers while extracting minerals and wood, and later cattle and agricultural products.

My father talks of the company known as ‘Lumber’ which had a sawmill near his mother’s house. It is the USA owned, Southern Brazil Lumber and Colonization Company (a subsidiary of Brazil Railway Company), whose interests were defended by hired gunmen. The company was allowed to cut 15 kilometres of the forest on either side of the railroad tracks, which, included my father’s village. The company would then own this land, which they offered for sale to European settlers, thus dispossessing squatters. Lumber’s headquarters was in Tres Barras, today a half hour car ride away from the village. The company devastated the entire region and by the time my father was a young boy he said that the trees were all cut and the sawmill barely functioning. He explained that their forest was how the Americans got the wood to build their houses. Lumber’s activities in the region would lead to the War of the Contestados during the first part of the 20th century which united Indigenous peoples, squatters and the unemployed. Over 8000 were killed and they lost the war. Installed today on Lumber’s former facilities is the Brazilian army’s largest training camp.

The government and colonising companies recruited Bugreiros, hunters of Bugres, hunters of Indigenous people, who were legally authorised to hunt and exterminate Indigenous peoples in Parana and the neighboring states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, thus making stolen lands available to settlers. Today, these are the three whitest states in Brazil. There are municipalities in these states with recognised official European languages such as Talian, and several German dialects: East Pomeranian, Plattdeutsch, and Hunsrueckisch. Still, to this day, no Indigenous language is recognised in these states. In some of these muncipalities, the teaching of German or Italian is mandatory. This is not such the case, in any municipality of Brazil, for an Indigenous lanugage. Proof of death was ears. Bugreiros could kill Indigenous people legally until 1914.

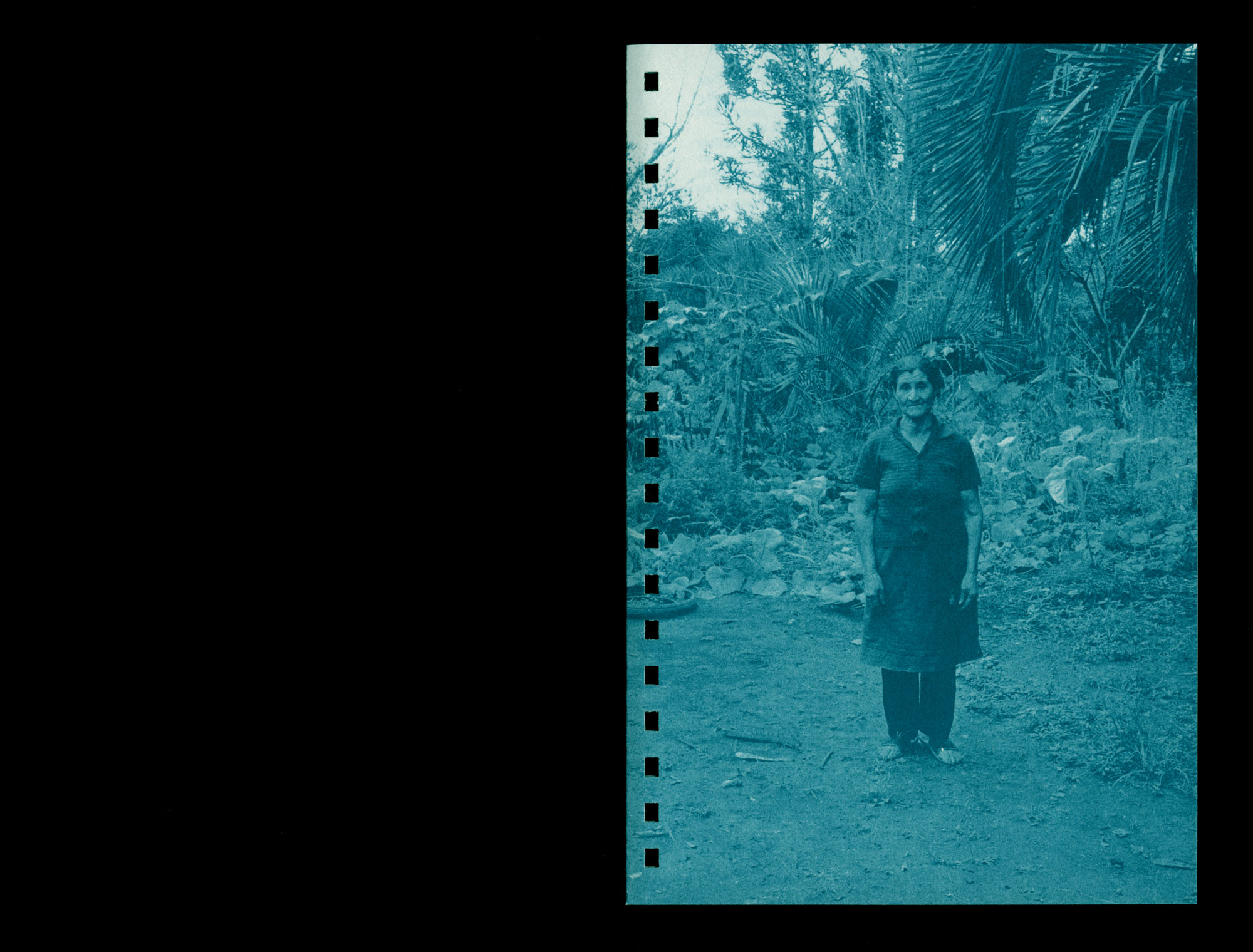

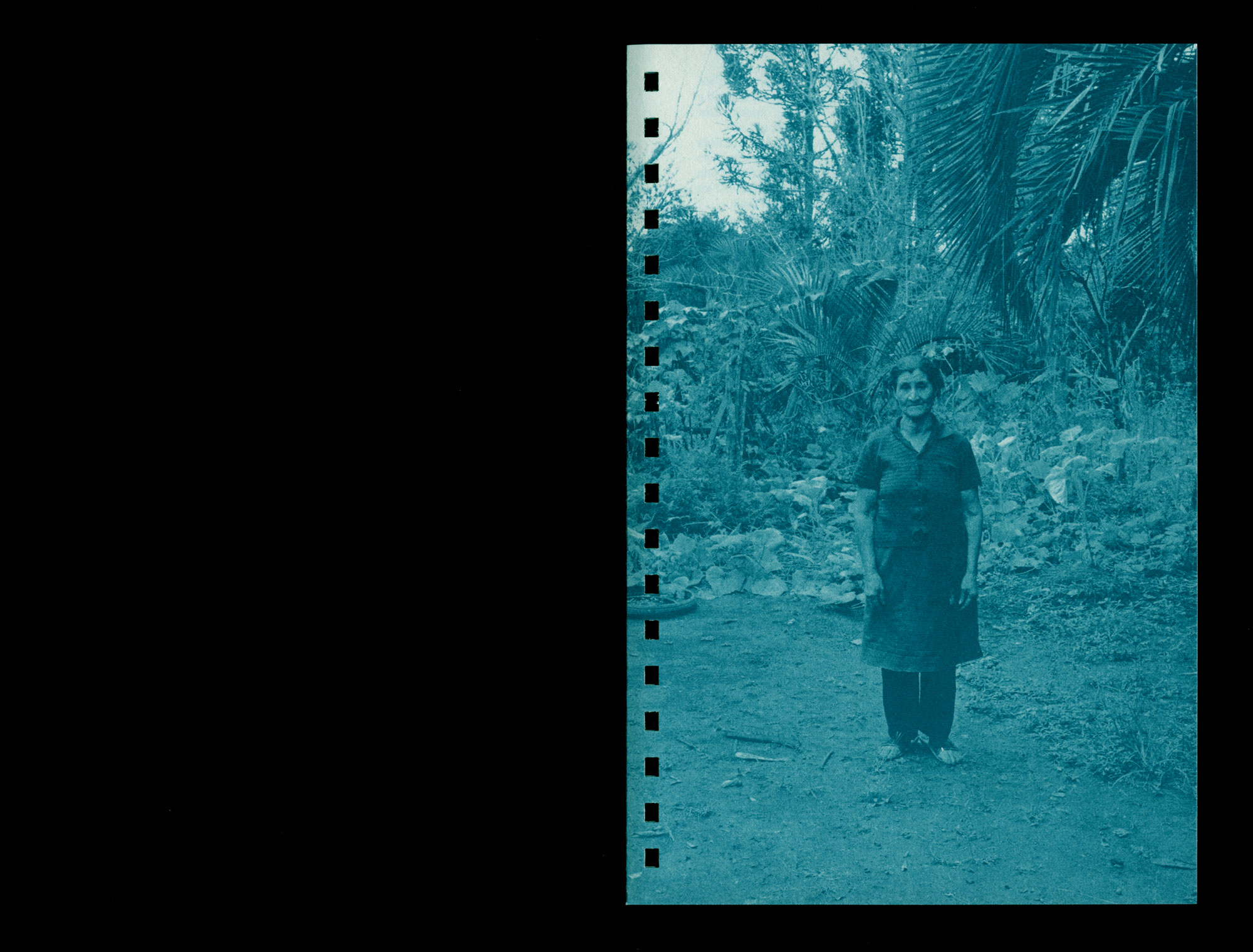

In my father’s village, there was no one who was Indigenous and who would admit so except Maria. I met her in 1983 when I returned to my father’s village as an art student during the military dictatorship with my new skills in photography and writing and asked, ‘What do we want the world to know about us?’ My favourite aunt took me to visit Maria who welcomed me into her home. She requested a special photograph of herself – with no kerchief on. She did not want foreigners to think she had white hair just because she was old. As she arranged her hair, she proudly said, ‘I’m ninety-eight and I don’t have one white hair. It’s all black. The people here think I’m Italian because of my black hair and fair skin but I am Bugre, pure Bugre. That’s why I don’t have white hair.’

Maria inverted that horrible word into pride. Maria was born in 1885, for the first 30 years of her life it would be legal to hunt and kill her.

Her daughter, of an Indigenous mother and father, does not consider herself Indigenous, neither do her grandchildren. On a visit to the village in 2017, her grandson along with my favorite aunt and I went to visit what remains of the forest, now on the private property of a fundamentalist evangelical pastor of German descent. As we arrived at the property he made derisive comments about Indigenous people by telling the workers on his land to put on some banana leaves and dance like ‘Indians’ and then he suggested to Maria’s grandson that he should read the ‘great book’, Mein Kampf, by Adolf Hitler.

In 2018, her daughter, gave me Maria’s house. It is a great honor and responsibility.

Trucks are now in the village and they come to extract lumber – this time eucalyptus, which has been planted throughout so much of Brazil and which further weakens and ruins the local earth.

Returning from the Great Guarani Council Aty Guasu elections in 2017, I got on a bus and was the only passenger. The driver wanted to talk and asked if I had been on holidays. I said no, I had been to the Guarani reservation. He did not know one was there and said that his grandmother had been Indigenous (and no, he did not know which ethnic group) and that he is proud of this and has tried to pass this onto his children. He is a Black man. He asked if he could take some Guarani classes – I said that they are excellent teachers.

During the same week, I took a taxi in São Paulo City and the driver said that his grandmother was an Indigenous woman from the northeast of Brazil. He would describe himself as white.

In São Paulo where my mother’s family is from – on maps of the early 20th century entire sections of the state was considered Indigenous territory. It is common in the local history for Indigenous women to have been forcibly removed from their communities and raped and forced into marriages with non-Indigenous men.

My mother had said to me while growing up, ‘When they come, flee.’ We all had our suitcases ready. Later, as an adult I asked her why she said this. She explained that her mother had told her this: ‘A woman who was caught was partnered to a violent husband whose children she did not want nor love.’ But her warning was an attempt to pass on survival skills in order to survive the invasion, which resulted in what is present day colonial Brazil.

While growing up my mother tried to train my wide feet to fit into European-styled narrow shoes. She offered her hard-earned money as a cleaning woman to pay to fix up my large nose and rid the epicanthic folds of my eyes. Her terror about what I looked like to her world was not unfounded.

In the colonial process the Indigenous body’s main use is for labor (not so in the English case where it is seen as an unwanted problem) and for the procreation of settler children. In this process few of us, due to historical realities, remain on original Indigenous territories. Many of us have ancestors who lost their courage (and we are not the ones who can condemn them in the midst of state and societal brutality and violence) and hid as best they could. A brave few, like Maria, in the midst of violent displacement and a genocide campaign made a place for herself and found joy and announced to the world, ‘I am Bugre, pure Bugre.’

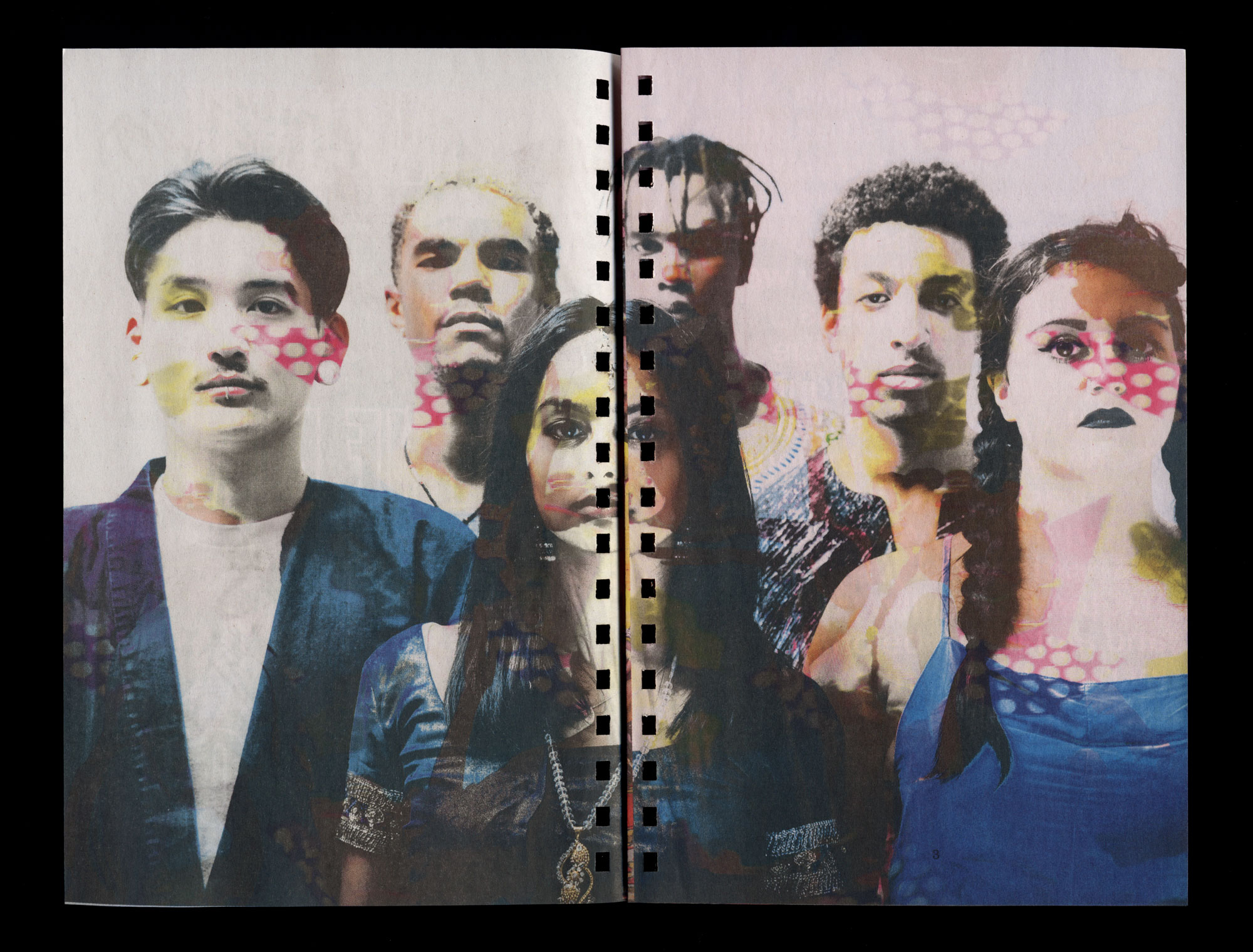

We, the offspring, are part of this Indigenous diaspora. As Noara Quintana has pointed out to me, it is a cultural diaspora. Our obligation is to support the land struggles of communities that fight for land.

A Canadian Indigenous thinker once said to me, ‘those of us who can pass and therefore can make believe we are white – it leaves us feeling dirty – you know those moments when someone says something racist and you can pass …’ It thus becomes important to identify ourselves publicly as being from the Indigenous diaspora.

In Brazil, the colonial government ‘s definition of an Indigenous person is someone who was born and lives on a reservation. This serves the purpose of further diminishing the Indigenous population. Some Indigenous communities strongly feel that both parents must be Indigenous. Some other communities strongly feel that both parents must be from the same ethnic group.

Colonial government policies only serve to weaken and destroy communities.

I have met people, over the past ten years, in Brazil, who will openly confess that their grandmother was Indigenous. Yes, it is almost always their grandmothers. It was the women who were taken as trophies and forced in most cases into relationships and violence against their bodies. As a Guarani activist said, these grandmothers are almost always Guarani. Sure, some of these people are romantic but some are not. Some are working class and some are Black – and it is not so easy for them to agree to further place themselves in marginalised categories for derision, further racism and yet even greater lack of power and yet they do.

Lately, I have met several young intelligent women with Indigenous grandmothers. One is a lawyer, and if the subject is Indigenous land rights – she adamantly defends it. Her grandmother would be proud of her. No, she does not know her grandmother’s people nor her reservation.

In respect of the communities which we no longer know and to which we belong to – how do we define ourselves? We who will not agree with the colonial definition of who Indigenous people are and thus with the disappearance of them. Shall we say we are ‘Bugre’? The de-ethnicised? If that is the only current space available to us, then as Maria, we will with pride say, ‘I am Bugre.’ Because colonial history happened on us.