Do you think, particularly within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, terms like urban, rural, and remote have also been used to disenfranchise communities?

Monday, September 2, 2019, Sydney

HP

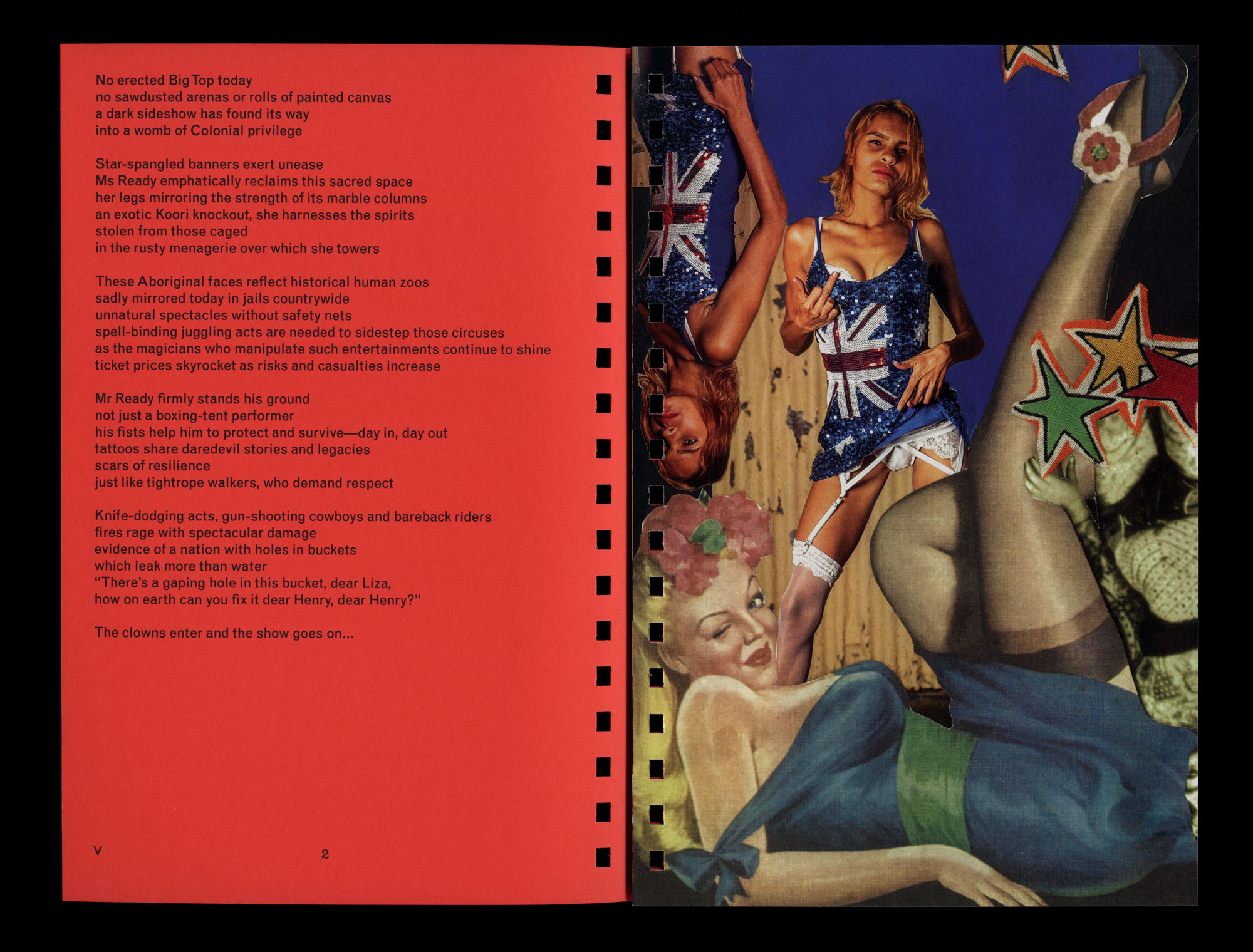

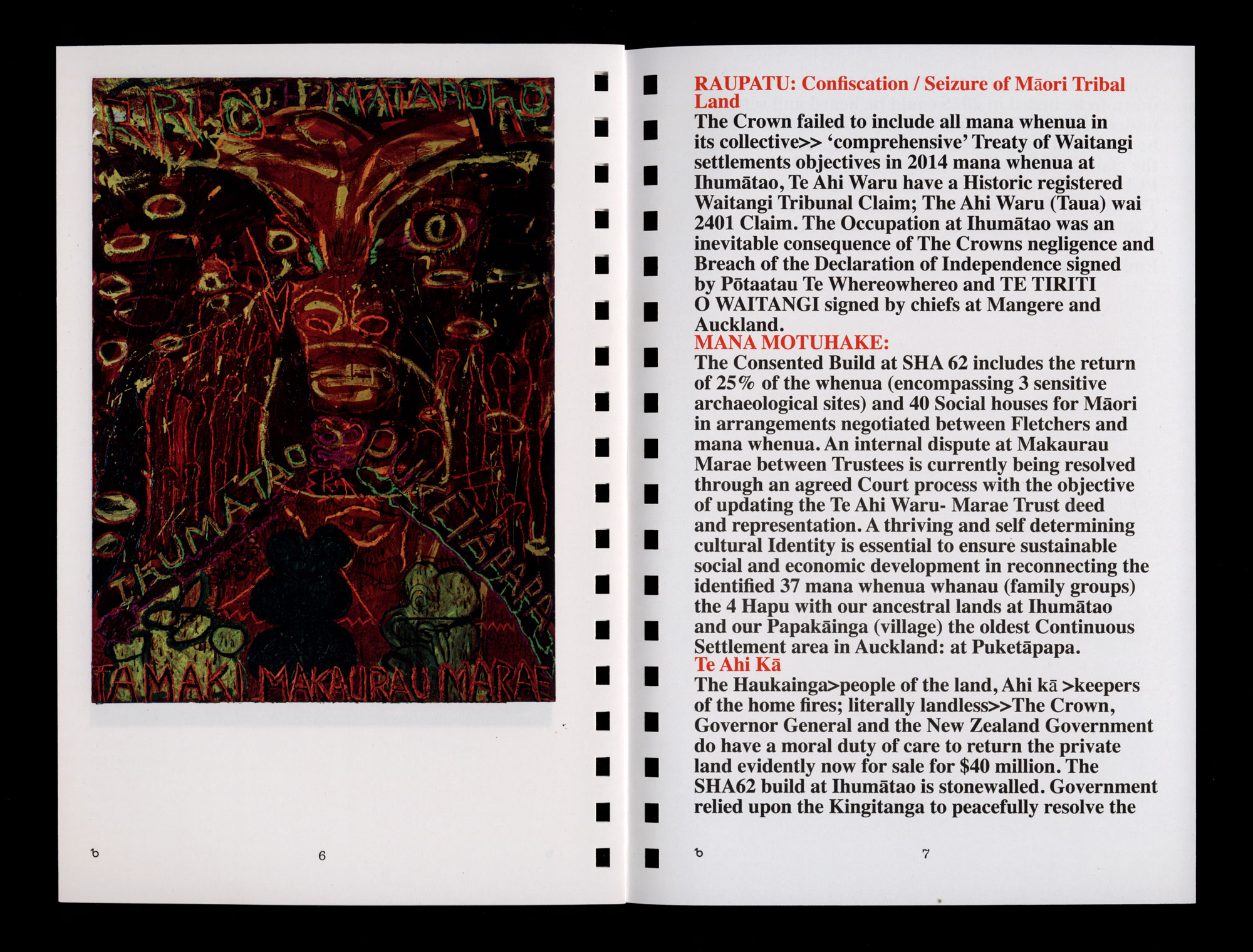

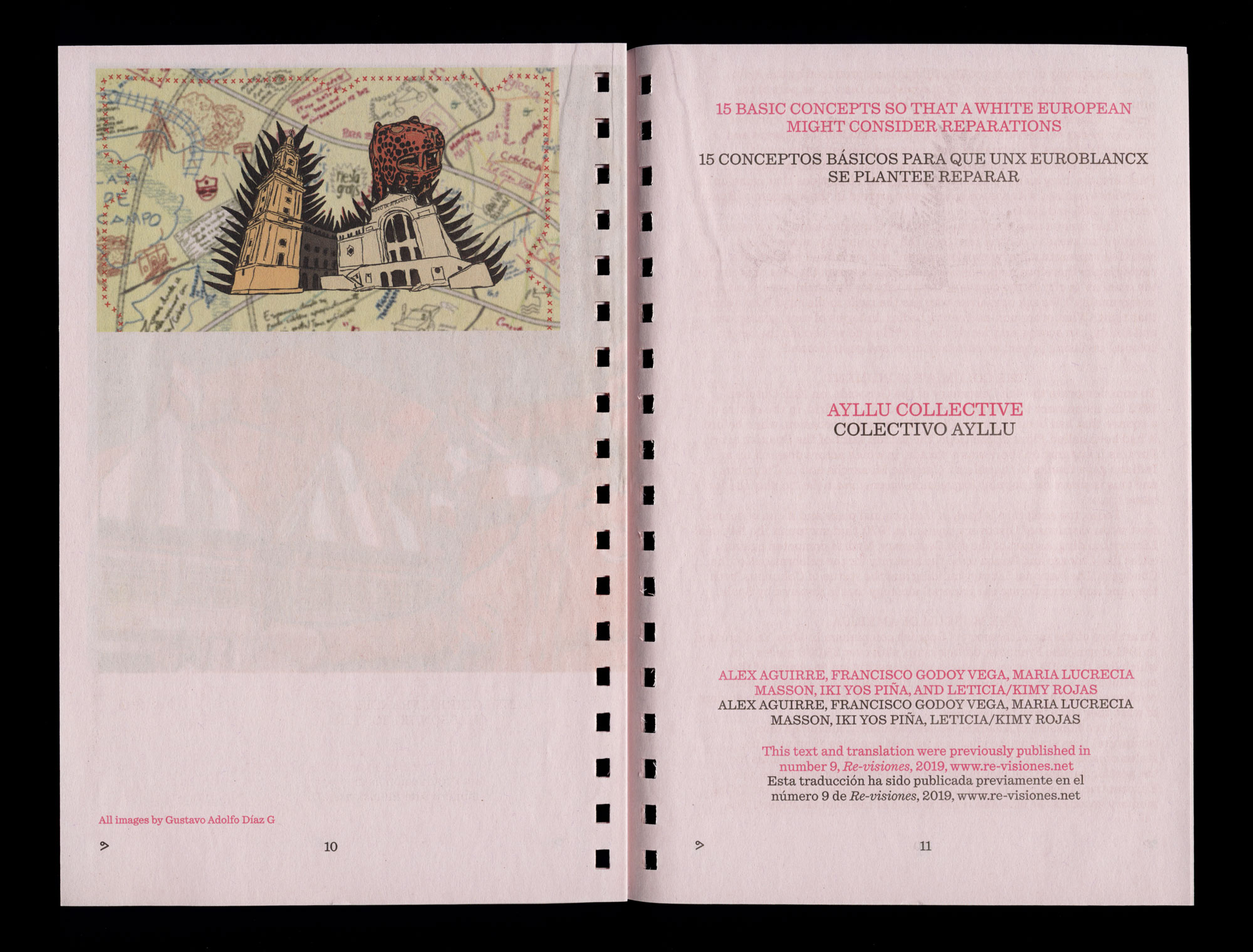

In 1992, for the 9th Biennale of Sydney, Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Cooperative presented a collaborative temporal art installation by Aboriginal and Latin American artists at The Performance Space. Called ‘Wiyana / perisferia (periphery)’, this satellite exhibition was about ideas of centre and periphery. It marked the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ landfall in the Americas and the International Year of the World’s Indigenous Peoples1. Close to three decades on, are those kinds of discussions still pertinent for you as an artist?

TA

I think they’re absolutely relevant. It’s so important to reflect on what has been achieved especially by our own people and communities. One would hope that the conversations and the realities of those conversations change over time, but sometimes they don’t and that is why reflection is important. You can monitor what has changed and what hasn’t, what strategies for change worked better than others. In saying this, I really do feel a sense of urgency now. We are facing new challenges, particularly in regard to critical environmental change. We are at a crucial moment that we must respond to now.

HP

How do those ideas of centre and periphery operate within the climate emergency, for instance?

TA

This is an important question because in regard to the climate emergency, it is the periphery that takes the brunt of catastrophic effects. So, we should be constantly checking in and listening to those ‘on the edge’ in regional and remote areas, the people at the forefront of the crisis, to really understand how it is affecting people. Unfortunately, this does not happen enough. The reality of it might not be in front of our face right now but for some people, it is. That is where we need to look for the answers, not wait till it comes to us. The sad reality with climate change is that Indigenous people are the least responsible for causing climate change yet the first to feel the impact of its devastating effects.

HP

A good example would be the Torres Strait Islander community’s complaint to the United Nations Human Rights Committee that the Morrison governments inaction regarding climate change is a violation of their human rights.

TA

Absolutely. Why are we not heeding these warning signs? The Torres Strait Islander community and our Pacific neighbours are the people whose voices need to be heard now – they are the voices we need to listen to. I feel a great disparity in how close something is affecting you and the actions we take. But everyone should be responding to this issue.

HP

Do you think, particularly within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, terms like urban, rural, and remote have also been used to disenfranchise communities?

TA

There is a history within art museums and galleries of institutional categorisations that inevitably change. They might make sense at a specific time. We know terms like rural, regional, contemporary, urban don’t assist us or represent us. I feel these categories serve a western purpose, not really an Aboriginal one. Institutions need to define these things to make sense of them: where do they fit, where will they be displayed and stored? They need a label, or the systems set in place won’t function. Sometimes I find it rather funny. I would like to think that institutions have moved beyond that way of thinking. I believe there is a much greater movement of bringing conversations together, rather than being separated.

Artworks all talk together and I like to look at those conversations in regard to what brings them together rather than what pulls them apart. Labels, ideas, spaces and places that were once separated and categorised are now being merged. Artists are talking and leading these conversations, it’s important in moving forward with our vernacular and our language to listen to them.

HP

In my experience, those terms are still often tied to notions of authenticity. So, if you are ‘remote’, you are the ‘real’ voice. And if you are ‘urban’ you are considered as a less authentic voice within the art world. Not by Indigenous people necessarily, but by the audience for the work. Another important and urgent discussion in Australia in terms of these kind of boundaries generated by the centre to categorise the periphery are about ‘peripherised’ gender and sexuality identities.

TA

Absolutely, the art community has really led that conversation. I remember those issues being spoken about but mainly in the art community and the queer community, not necessarily in the broader social mainstream. But when artists make work, the conversations follow. So you really see the effect that art does have on the world around us. Art plays a very key role in bringing those conversations to the forefront for the rest of society to follow and converse about the artwork and understand those ideas through the vessel that artists are using, that is their art.

HP

Artistic Director, Brook Andrew, has chosen ‘NIRIN’, a Wiradjuri word that can be translated as ‘edge’, as the title for 22nd Biennale of Sydney. He says ‘NIRIN is not a periphery, it is our centre and it expresses dynamic existing and ancient practices that speak loudly. NIRIN de-centres, challenges and transforms dominant narratives.’2 And he’s also said it’s about ‘moments of transition and a sense of being in the world that is interconnected.’3 This relates to what you were saying before, the common thread, the conversation. What other concepts or ideas in your experience might bear a relationship to this idea of ‘NIRIN’ or the ‘edge’?

TA

It’s very interesting when you use Indigenous language to define or understand something, or as a key concept. I’m finding that with what Brook has done with the Biennale and the way it reflects my life, as well as the intrinsic link Indigenous language has to nature. In my language ‘homeland’ and ‘heart’ is the same word, there are beautiful little nuances like that. So, we become much more attached to the world around us rather than as singular entities or individuals. I think that’s the idea; it’s not the actual periphery, it’s the centre, it’s the core of our being. And, I think that is, again, this common thread with Indigenous people, Indigenous language and the way in which we position ourselves in the world. It’s not a singular experience, it’s a group experience and that group includes what actually surrounds us ... what is living, and that is, theoretically, everything. So, NIRIN is a beautiful and important play on words.

It’s also not about connecting, the connection already exists. It’s about not disconnecting.

HP

How are these ideas present in your work as an artist, as a thinker, a writer, a television presenter? Is there a particular work or a genre within your practice that you think really deals with this idea, this edginess?

TA

For me, it’s pushing something to the edge. It’s taking it to an extreme point of unpacking it, unloading it, challenging the conceptual ideas. Then pulling back from that and understanding how from that platform it successfully translates into art.

With my work in the Biennale it is this fundamental idea of Country and memory and healing, in a way. It was a thought of not just putting a sculpture onto land. There’s a whole other rejuvenation process that has to be done in terms of the healing of space and place before the idea of an artwork can even sit there. It’s not pre-empting or getting ahead of ourselves. It is about paring back and understanding what needs to happen for things to grow.

And in the case of our people and the trauma that’s attached to some sites and the land, we’ve actually got to treat and tread carefully and understand what’s gone on there.

HP

Because it is, as you say, our heart and our home. How do artists bring their heart and home into their art?

TA

We share. We look at equality as the acceptance of difference. What I mean by saying that is, it is our difference that bring us together. And understanding those differences. Learn from them. Understand why someone does something one way. Is that part of their history, part of their culture? Is it a part of their way of living?

Don’t look at what we can get from a situation, but what we can give in a situation.

-

Wiyana / perisferia (periphery), 1992, was a collaborative temporal art installation by Aboriginal and Latin American artists curated by Hetti Perkins and Lilliana E. Correa for Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative at the Performance Space, Sydney, for the 9th Biennale of Sydney. ↩

-

Brook Andrew, quoted in ‘Biennale of Sydney announces 2020 exhibition: NIRIN’, media release, 9 April 2019. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩