Temporality is circular, particularly when we view it through an Indigenous genealogical prism where all beings are linked in kinship. Pleasure is emancipatory, particularly when we view it through an Indigenous cumlines perspective where all desires carry kinship. That I am able to write these few words, to bear witness to my journey up until now and afterwards, it is solely because I have benefited from the innovative practices and multidirectional support of Indigenous artists, thinkers and curators from multiple nations including Sāmoa: Aunty Sana Balai, Kimba Thompson, Julie Nagam, Brian Martin, Yuki Kihara, Dan Taulapapa McMullin, Marcel Melthérorong, Heather Igloliorte, Lindsay Nixon, Rosanna Raymond, Angela Tiatia, Kimberley Moulton, Lana Lopesi, Tarah Hogue, Freja Carmichael, Sarah Biscarra Dilley, Mylène Guay, Caroline Monnet, Camille Larivée, Sébastien Aubin, Joshua Tengan, Ioana Gordon-Smith, Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick, Vehia Wheeler, Allan Haeweng. Through this text, I honour you for all that you advance and complexify.

Let us return to late spring of this year, where I find myself in a Montreal bookstore listening to a grand dame of (francophone) Indigenous literature, Joséphine Bacon, Innu, who reveals during a first discussion with her (anglophone) counterpart, Lee Maracle, Stó:lō, ‘I really want my language to never die.’1 Here she is speaking about Innu-aimun, having started writing literature after seeing her grandfather read and reread the Bible in it. As there were no other texts available in Innu-aimun and he was not literate in French, he was forced to continue with Genesis and the Gospel. Then she continued to write. Our pleasure is to see between these current texts those histories long held captive underground.

There are many reasons why I do not write this text in the Sāmoan language, that is to say, the tongue of the Sāmoan archipelago, the former Manu‘a empire subjugated for centuries by the Tongan empire, since divided into a United States colony in the east, and a German, then New Zealand colony, then independent state in the west. I especially wish to arrest the colonial structures, faiga fa‘akolonē, that pushed the majority of my people to leave, to live and survive elsewhere, on the lands of other First Peoples in all directions. Amongst these is the international date line that bifurcates the archipelago between yesterday and today, this Protestant temporality decreed from Greenwich, between northern and southern spheres of influence. To insist on the agency of the language we have suffered, and the language we have chosen, I will take up the words of the celebrated Innu writer Naomi Fontaine. She who commits to relearning her language in order to make it shine: ‘It is not my choice not to write in Innu. This decision was made well before I was born. It was written into all the assimilationist measures that my grandparents, parents and I were subjected to. I was educated in French. I was made to believe that my language was dying.’2

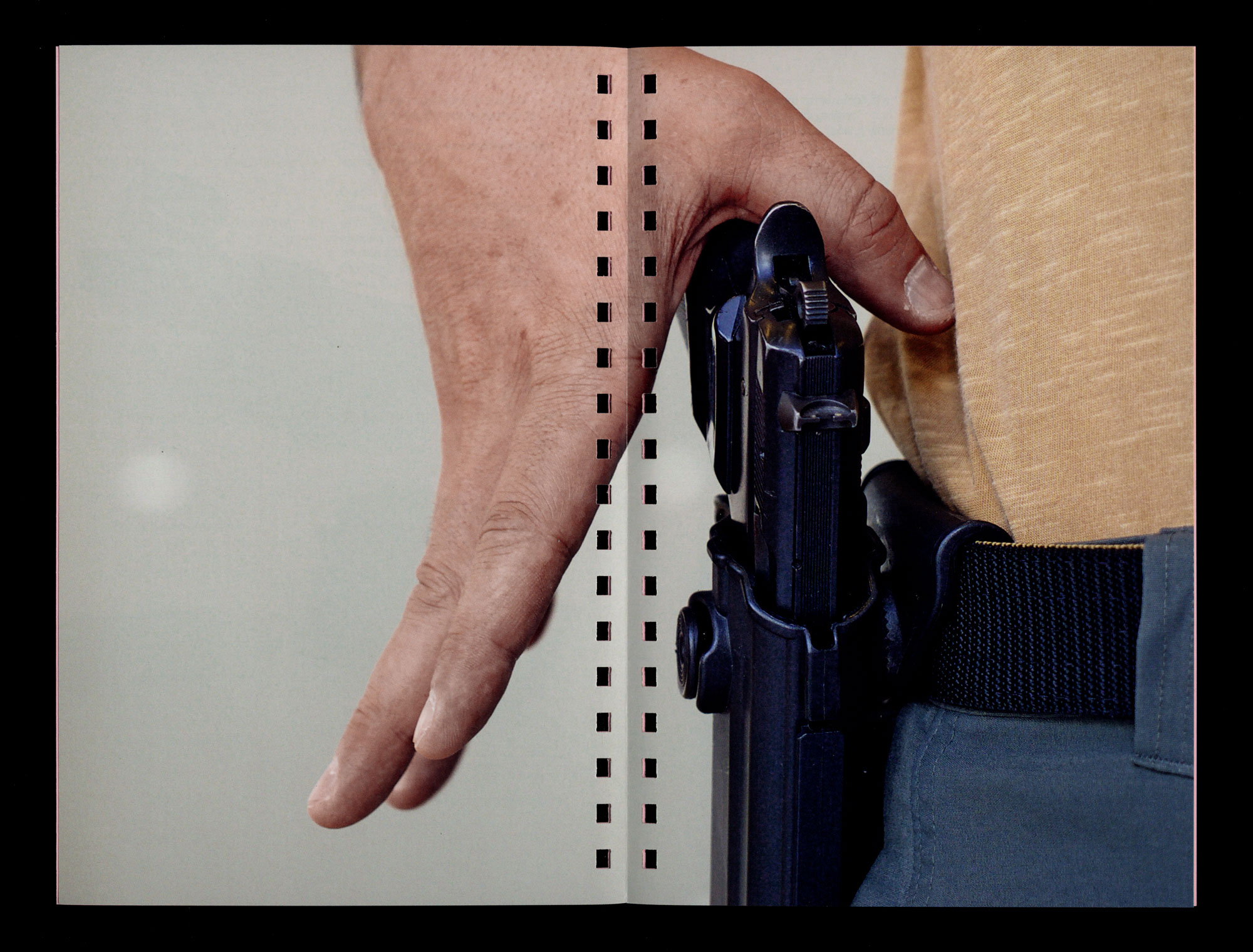

Literacy in English followed the translation of the Bible into Sāmoan, as was the case in numerous language areas around the Great Ocean. Here, I raise the spectre of mass evangelisation in the 1830s, the massive alienation of arable lands to become plantations for sugarcane, cacao, vanilla, coffee, coconuts. The dehumanisation completed in part by armed forces and imported far-off wars, and in part by large-scale tourism, seeking to expropriate, possess, and dominate bodies, landscapes, softness, sunsets. The climate crisis diminishes islands, lagoons, mountains, villages, sacred sites, associated knowledges of archipelagos in order that we may no longer have, see, fall, despite far-flung industrialised countries being in fact primarily responsible.

-

This quotation is taken from my notes taken at an event held on 3 May 2019 titled Lee Maracle et Joséphine Bacon en discussion, at the Drawn & Quarterly bookstore in Montréal. ↩

-

The translation of this quotation from French to English is my own. Naomi Fontaine, 2019, Shuni: Ce que tu dois savoir, Julie [Shuni: What you should know, Julie], Mémoire d’encrier, Montréal, p. 38. ↩

La temporalité est circulaire, particulièrement lorsqu’on l’examine d’un prisme généalogique autochtone où tout être se lie de parenté. Le plaisir est émancipateur, particulièrement lorsqu’on l’examine d’une perspective de lignées de chair autochtones où tout désir est porteur de relation. Si je suis capable d’écrire ces mots pour un peu témoigner de mon cheminement jusqu’ici et au-delà, c’est bel et bien parce que je suis héritier des démarches innovantes et du soutien multidirectionnel des artistes penseur.e.s commissaires autochtones de multiples nations dont samoane : Tantine Sana Balai, Kimba Thompson, Julie Nagam, Brian Martin, Yuki Kihara, Dan Taulapapa McMullin, Marcel Melthérorong, Heather Igloliorte, Lindsay Nixon, Rosanna Raymond, Angela Tiatia, Kimberley Moulton, Lana Lopesi, Tarah Hogue, Freja Carmichael, Sarah Biscarra Dilley, Mylène Guay, Caroline Monnet, Camille Larivée, Sébastien Aubin, Joshua Tengan, Ioana Gordon-Smith, Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick, Vehia Wheeler, Allan Haeweng. Je vous rends hommage pour tout ce que vous faites avancer, nuancer, par le présent texte.

Repartons au printemps tardif de cette année, où je me retrouve dans une librairie montréalaise à l’écoute d’une grande dame de la littérature autochtone (francophone), Joséphine Bacon, Innue, qui divulgue lors d’une rencontre inédite avec son homologue (anglophone), Lee Maracle, Stó:lō : « Je veux beaucoup que ma langue ne meure jamais ».1 Elle parle justement de l’innu-aimun, s’étant projetée dans la littérature après avoir assisté à la lecture et relecture des versets bibliques en innu-aimun par son grand-père, qui était contraint, faute d’autre texte en innu-aimun ou d’alphabétisation en français, de tourner autour de Genèse et d’Évangile. Puis elle a continué à écrire. Notre plaisir c’est d’entrevoir dans tous ces écrits actuels des histoires restées sous-jacentes pour bien trop longtemps.

Il y a nombre de raisons pour lesquelles je ne rédige ce texte en langue samoane, c’est-à-dire le parler de l’archipel des Samoa, ancien empire de Manu‘a assujetti pendant des siècles par l’empire des Tonga, depuis divisé en colonie étatsunienne à l’est et colonie allemande puis néo-zélandaise puis état indépendant à l’ouest. Surtout je désire retenir les structures coloniales, « faiga fa‘akolonē », qui ont poussé une majorité des mien.ne.s à partir vivre et survivre ailleurs, sur les terres d’autres peuples premiers dans toutes les directions. Parmi celles-ci il y a la ligne internationale de la date qui bifurque l’archipel entre hier et aujourd’hui, cette temporalité protestante divulguée de Greenwich, entre sphères d’influence nordique ou sudiste. Pour insister sur l’agentivité de la langue subie et de la langue choisie, je reprends les paroles de la célèbre écrivaine innue Naomi Fontaine qui se lance désormais dans le réapprentissage de sa langue pour mieux la faire rayonner : « Ce n’est pas mon choix de ne pas écrire en innu. Cette décision a été prise bien avant ma naissance. Elle était inscrite dans toutes les mesures assimilatrices que mes grands-parents, parents et moi, avons subies. On m’a instruit en français. On m’a fait croire que ma langue était mourante ».2

L’alphabétisation en anglais a suivi la traduction de la Bible en samoan, comme pour de nombreuses aires langagières à travers le Grand Océan. J’évoque ici l’évangélisation en masse dans les années 1830, l’aliénation considérable des terres rentables pour devenir plantations alimentant canne à sucre, cacao, vanille, café, noix de coco. La déshumanisation achevée en partie par les forces armées, les guerres importées de loin, et en partie par le tourisme d’ampleur, cherchant toujours plus à exproprier, posséder, dominer les corps, les paysages, la douceur, la chaleur, les couchers du soleil. La crise climatique rabaisse les îles, les lagons, les montagnes, les villages, les lieux sacrés, les savoirs contigus des archipels afin de ne plus avoir, voir, choir, bien que les pays industrialisés lointains soient en majorité les responsables.

My hi/story begins on the lands of the Yuwi First Nation and continues on those of multiple other Indigenous territories including our own in the Sāmoan archipelago. My hi/story begins through the meeting of a young Sāmoan and Chinese dancer-creator seeking overseas adventures and a young Persian engineer-dreamer seeking home and balance. My hi/story begins with the creation of multiple settler and exploitative colonies combining organised dispossession with cumulative violence by European and Asian empires’ flavours. I found myself learning French to be able to survive the isolation from ancestral language communities because I was living in the Queensland colonial hinterland, on lands wrested from First Nations for the English queen. After I met young Kanak interns. After trying to learn Spanish, Afrikaans, Japanese, Persian, Sāmoan. Before the time when I became creolophone, able to express myself with hundreds of thousands in Bislama and Tok Pisin, the creole tongues of Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea.

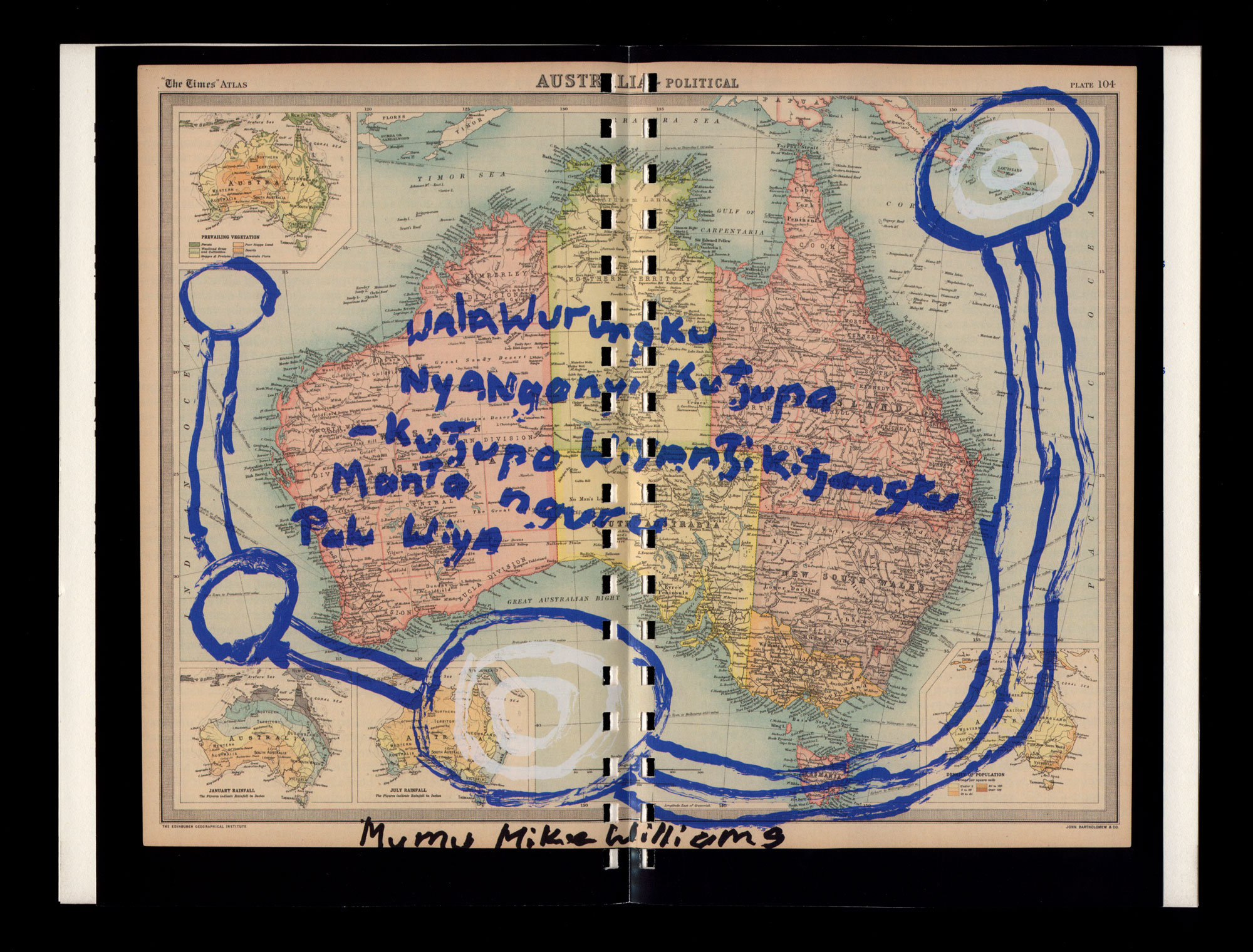

From much later on, I consider these parts of my life with a healthy perspective of a potential arrivant to the Québec and Northern Australian contexts. I take up Stó:lō thinker Dylan Robinson’s term ‘arrivant’, which shows more openness and respect than the more opaque notion of ‘im/migrant’, with a fortunate understanding of these contexts because most of my friends are part of the Indigenous and queer communities of Montréal and Darwin. In larger western cities, the performance of respectability of urban populations goes beyond the bounds of cultural zones without really considering the sonic and intellectual impact of ancestral place names linked to particular territories as well as those more recently attached to them during settler colonisation. ‘Tiohtià:ke’ or ‘Osherà:ke’ in Kanien’kéha, ‘Mooniyang’ in Anishinaabe, ‘Molian’ in W8banaki, ‘Te ockiai’ in Wendat do not correspond to the same relational territory as that which constitutes ‘Montréal’. Acting as they do as haunting ghosts from parallel Indigenous worlds, so linked in given kinship to all creation, precisely that which the entirety of non-Indigenous speakers do not have access. These known Indigenous place names hold space for those that today we do not know but which the terroirs, the storied places, have never forgotten. As is the case for each named place on a great river or a small waterway, where nations, language areas, animal, fish and bird migrations, and lifestyles, flow into each other. These cannot be summarised or gathered together in the enlarged place names alone, such as Sydney, Toronto, St Lawrence, Murray, Mississippi, Goulburn, Melbourne, Montréal.

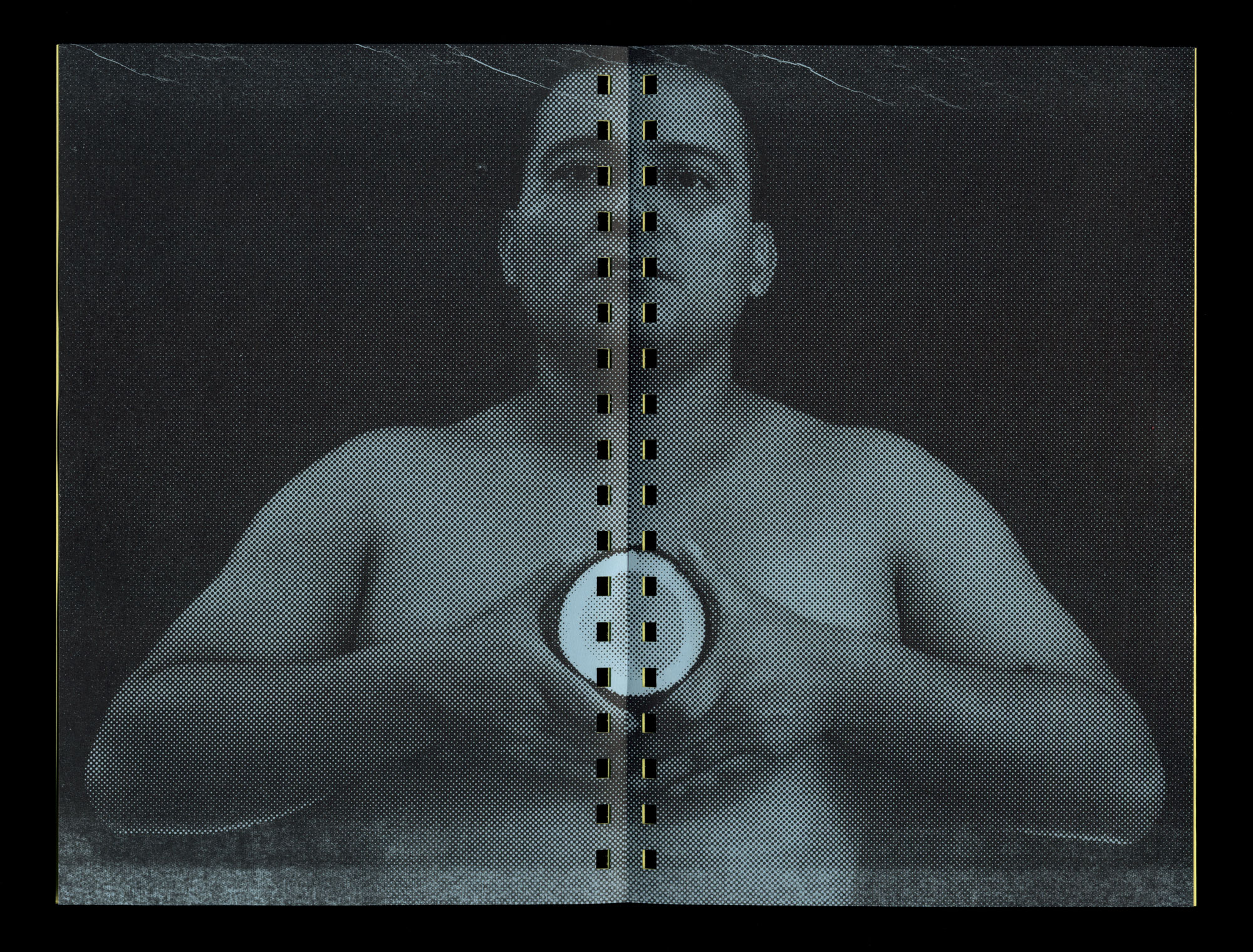

In order to speak of Indigenous pleasures, we must be able to literally immerse ourselves in fluid states, necessary to wellbeing, to sensuality, to fulfilment, to openness. We must be able to embody ancestral knowledges that teach us that we do not have bodies. To take up Tlingit curator and writer Candice Hopkins’ term, our bodies are ‘visual manifestations’ of our ancestral cumlines, which can be expressed in these Sāmoan concepts: toto for soil and blood, fanua for earth and placenta. Our bodies are the skins, waters, airs, lands of the nations where we come from. We are beings linked to water on physical and philosophical levels. The Sāmoan, Hawaiian and Hakö ceremonial practices that I am familiar with centre on the purifying use of fresh water, grated turmeric or salt water, and coconut water to gather the ancestors of each place. If Indigenous spoken language, or the subverted colonial language, can be appreciated as Indigenous pleasure, and as a sign of the openness of colonising states, I would like to push us even further.

Mon histoire commence sur les terres de la Première Nation Yuwi, continue sur celles de plusieurs autres territoires autochtones y compris le nôtre dans l’archipel des Samoa. Mon histoire commence dans la rencontre d’une jeune danseuse créatrice samoane et chinoise en quête d’aventures outremer et d’un jeune ingénieur rêveur persan en quête de repaysement et d’équilibre. Mon histoire commence avec la création de plusieurs colonies de peuplement et d’exploitation mêlant dépossessions organisées et violences cumulatives aux couleurs d’empires européens et asiatiques. Je me retrouve à apprendre le français pour pouvoir survivre à l’isolement des communautés langagières ancestrales car vivant dans l’arrière-pays de la colonie du Queensland, terres arrachées aux Premières Nations pour la reine d’Angleterre. Après avoir rencontré de jeunes stagiaires kanak. Après m’être essayé à l’espagnol, à l’afrikaans, au japonais, au persan, au samoan. Avant la période où je deviens créolophone, capable de m’exprimer avec des centaines de milliers en bichlamar et tok pisin, les parlers créoles vanuatais et papou.

De bien plus tard, je considère ces étapes de ma vie avec un regard sain issu de ma perspective d’arrivant possible aux contextes québécois et nord-australien. Je reprends le terme « arrivant » du penseur stó:lō Dylan Robinson car ceci signale davantage d’ouverture et d’apprivoisement que dans la notion plus opaque de « im/migrant.e ». Avec une connaissance chanceuse de ces contextes car la plupart de mes ami.e.s sont des communautés autochtones et queers de Montréal ou de Darwin. Je note ici la performance de respectabilité des populations urbaines des grandes villes occidentales qui dépasse les bornes d’aires culturelles sans pour autant songer à l’impact sonore, intellectuel des toponymes ancestraux liés à certains territoires en plus de ceux plus récents du temps de la colonie de peuplement. « Tiohtià:ke » ou « Osherà:ke » en kanien’kéha, « Mooniyang » en anichinaabé, « Molian » en w8banaki, « Te ockiai » en wendat ne correspondent pas au même territoire relationnel que ce en quoi constitue « Montréal ». Ces premiers agissant comme des fantômes hanteurs d’univers parallèles, autochtones donc liés de parenté reçue à toute l’existence, auxquels la totalité des locuteurs allochtones n’ont pas accès. Ces toponymes autochtones connus prennent place pour ceux que nous ignorons de nos jours mais que les terroirs, les lieux à récits, n’ont jamais oublié. Comme la particularité de chaque lieu nommé sur un grand fleuve ou un petit cours d’eau, où se succèdent nations, aires langagières, migrations d’animaux, de poissons et d’oiseaux, et modes de vie. Ceux-ci ne se résument pas ou ne se rassemblent pas dans les seuls toponymes élargis comme Sydney, Toronto, St-Laurent, Murray, Mississippi, Goulburn, Melbourne, Montréal.

Pour pouvoir parler du plaisir autochtone, il faut pouvoir s’immerger littéralement dans des états fluides, nécessaires au mieux-être, à la sensualité, à la plénitude, à l’ouverture. Il faut pouvoir incarner le savoir ancestral nous apprenant qu’en fait nous n’avons pas de corps. Pour reprendre le terme de la commissaire et auteure tlingit Candice Hopkins, nos corps sont les « manifestations visuelles » de nos lignées de chair ancestrales, ce qui s’exprime par ces concepts samoans : « toto », le sol, le sang ; et « fanua », la terre, le placenta. Nos corps sont les peaux, les eaux, les airs, les terres des nations d’où nous sommes. Nous sommes des êtres liés sur les plans physique et philosophique à l’eau. Des pratiques cérémonielles samoanes, hawaïennes et hakö qui me sont familières se concentrent sur l’emploi purificateur de l’eau fraîche, de l’eau au curcuma râpé ou au sel, et de l’eau de coco pour rassembler les ancêtres de chaque lieu. Si la langue autochtone verbale, ou celle contournée de la colonisation, peut être appréciée comme du plaisir autochtone, et marqueur d’ouverture des états colonisateurs, je voudrais nous pousser plus loin encore.

How do Indigenous sensual languages express themselves? Do fa‘atinoga, ceremonial performative actions, form an Indigenous sensual language that calls upon ancestral presences and audiences of multiple dimensions? How can we heal ourselves and come to terms with ourselves as sensual beings, knowing full well that we still need a cultural renaissance, a resistance to the colonial legacy that has never left our imaginaries? Can the verbs we use to describe the antics with a lover – feed, lick, eat, devour, rim, furrow, pour – be understood as affective cannibalism?

All these questions push me to recognise the stagnation of Indigenous pleasure when under states of missionary and mediatic control. I believe that non-colonial actions, having as power relations the chosen kinship of cumlines and the received one of bloodlines, and non-exploitative domination, can convey tenderness, hardness, futurity. Beyond European notions of taboo, deviancy, normality. Through appreciating sensual language actions, which are equal to the sounds of verbal languages, these demonstrate the fallibility of our current oppression by slave-driving capitalism, plantation-mongering Christianity. Finally, they hijack each effort to shame and erase our bodies, our bodies who we are.

I believe that certain types of recurring cannibalism in the sexual life of everyone can, when involving Indigenous persons, realise other temporalities. In order to relearn our roots, our ancestral-future knowledges, our guardian spirits, our god-goddesses, our animal relationships, we need to imagine or renew ourselves as fa‘afafine, fa‘atama, Two-Spirit, queer, trans, non-binary and more. Teasing around cheeks, ass, pleasure, diving deep, eating, feeding, rimming, furrowing, sometimes with the added rush of poppers. I think we need to move our tongues, our bodies, get them to speak, propel, touch, be tender, so that we can become healthy, in heterogeneous brilliance. We will be even more sensual after Gregorian shame-time.

Comment les langues autochtones sensuelles s’expriment-elles ? Est-ce que les « fa‘atinoga », gestes de performance cérémonielle, forment une langue autochtone sensuelle qui appelle aux présences ancestrales et aux publics de dimensions plurielles ? Comment pouvons-nous nous guérir et assumer pleinement comme êtres sensuels, sachant qu’il nous faut toujours une renaissance culturelle, une résistance au legs colonial jamais parti de nos imaginaires ? Est-ce que les verbes employés pour décrire les ébats avec son amant.e – manger, lécher, bouffer, dévorer, janter, sillonner, verser – peuvent se résumer en cannibalisme affectif ?

Toutes ces questions me poussent à reconnaître la stagnation du plaisir autochtone lorsqu’il s’agit d’états de contrôle missionnaire et médiatique. Je propose que des gestes non-coloniaux, ayant comme rapports de force la parenté choisie des lignées de chair et celle subie des lignées de sang et non la domination exploitante, peuvent véhiculer la tendresse, la dureté, la futurité. Au-delà des conceptions européennes du tabou, de la déviance, de la norme. Par la remise en valeur des gestes des langues sensuelles, qui égalent aux sons des langues verbales, ceux-ci démontrent la faillibilité de notre oppression présente par le capitalisme esclavagiste, le christianisme plantationniste. Et au final, détournent toute tentative de déshonorer, d’invisibiliser nos corps, nos corps qui nous sommes.

Je propose que certaines formes de cannibalismes récurrents dans la vie sexuelle de tout le monde puissent, en impliquant des personnes autochtones, réaliser d’autres temporalités. Pour nous réapprendre nos racines, nos savoirs ancestraux-futurs, nos esprits gardiens, nos dieux-déesses, nos relations animales, il nous faut nous imaginer ou renouveler en tant que personnes fa‘afafine, fa‘atama, bispirituelles, queers, trans, non-binaires et plus. Taquiner autour des fesses, du cul, du plaisir, s’immerger profondément, manger, bouffer, janter, sillonner, des fois avec l’élan ajouté de poppers. Je pense qu’il nous faut remuer nos langues, nos corps, les faire parler, mouvoir, toucher, tendrer, afin de devenir sain.e.s, en brillance hétérogène. Nous serons encore plus sensuel.le.s après la honte-temporalité grégorienne.