On Lord Howe Island, 600 kilometres off the east coast of Australia, is a unique forest where seabirds and palm trees have evolved an unexpected and intimate relationship. Nowhere on Lord Howe do the birds exist without the palms, and no stand of palms exists in the absence of the birds. Bird and tree are one. Nature is whole.

As an ecologist, born into an era of ‘jobs and growth’, it’s increasingly rare to witness and document such intact ecosystems. And so, every year for the past decade, I have counted down to the month of April, to the moment when I can return to the palm forest. My happy place, where I become whole.

So, ‘why April?’ you ask. My arrival is, oddly enough, synchronised with the departure of the birds I’m there to protect. Over the preceding three months, the adult shearwaters (or ‘muttonbirds’) on Lord Howe Island have been working hard to raise their chicks on a diet of fish and squid sourced from the adjacent waters of the Tasman Sea. By late April, the chicks are grown and it’s time for their first flight out to sea. They do this solo, the parent birds long gone. And they do this never actually having seen the ocean.

Emerging from the depths of their burrows for the first time must be a daunting task, but the chicks are driven by hunger and instinct. As the sun sets, we meet for the first time, among the palms, so I can record key measures of population health, such as chick body mass. The chicks are sporting some truly remarkable hairdos, as remnants of their fluffy down hangs on in a few awkward places. One has a mullet, another a mohawk, and one looks like my grandfather with little tufts coming out his ears.

During my first trip to Lord Howe Island in 2007, I struggled to communicate with my colleague due to the raucous noise of the colony. Each bird screaming ‘pick me, pick me’ at the top of its tiny lungs. The forest was so full of life we had to stand side-by-side to complete any work. I must have shouted ‘huh?’ a hundred times that year.

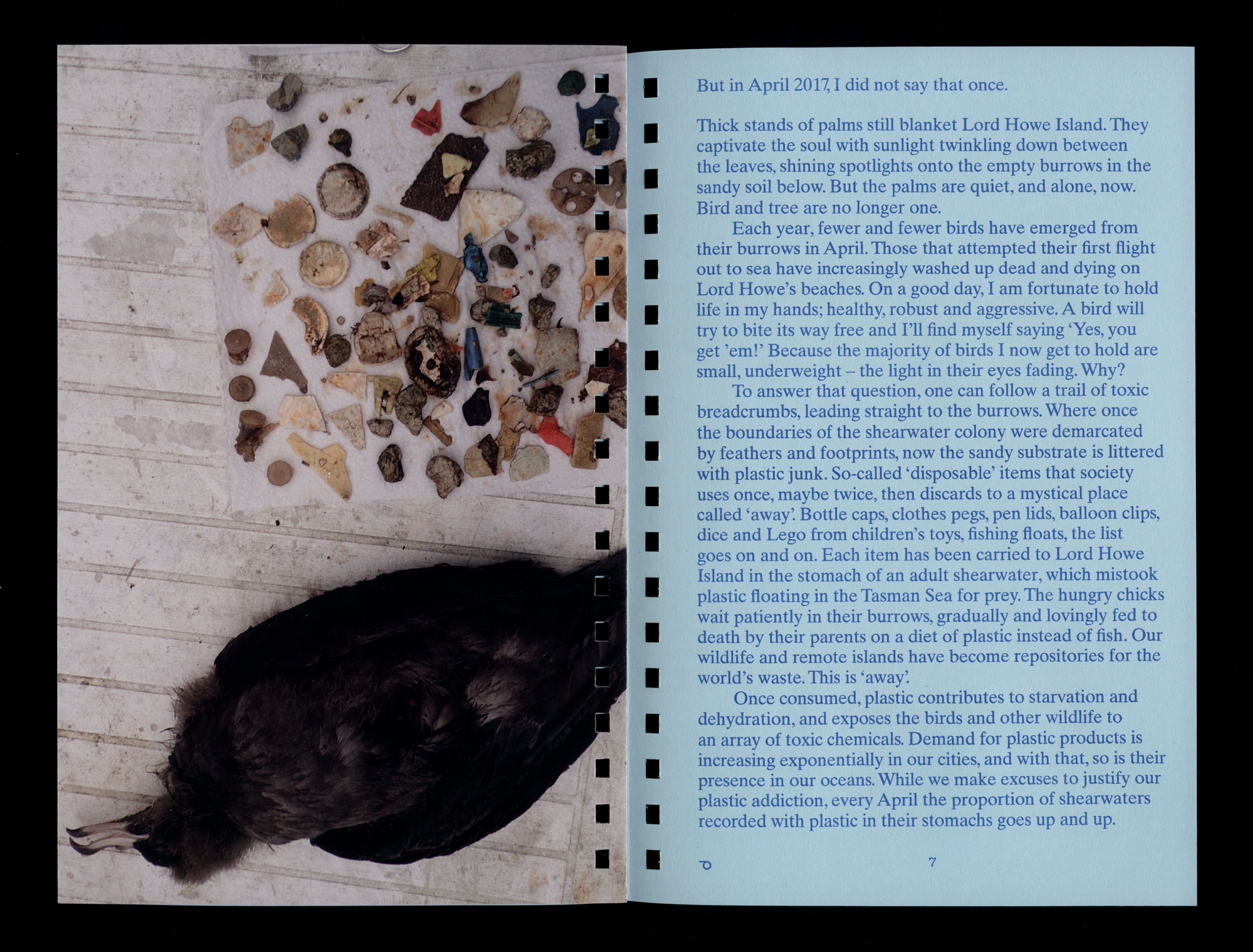

But in April 2017, I did not say that once.

Thick stands of palms still blanket Lord Howe Island. They captivate the soul with sunlight twinkling down between the leaves, shining spotlights onto the empty burrows in the sandy soil below. But the palms are quiet, and alone, now. Bird and tree are no longer one.

Each year, fewer and fewer birds have emerged from their burrows in April. Those that attempted their first flight out to sea have increasingly washed up dead and dying on Lord Howe’s beaches. On a good day, I am fortunate to hold life in my hands; healthy, robust and aggressive. A bird will try to bite its way free and I’ll find myself saying ‘Yes, you get ’em!’ Because the majority of birds I now get to hold are small, underweight – the light in their eyes fading. Why?

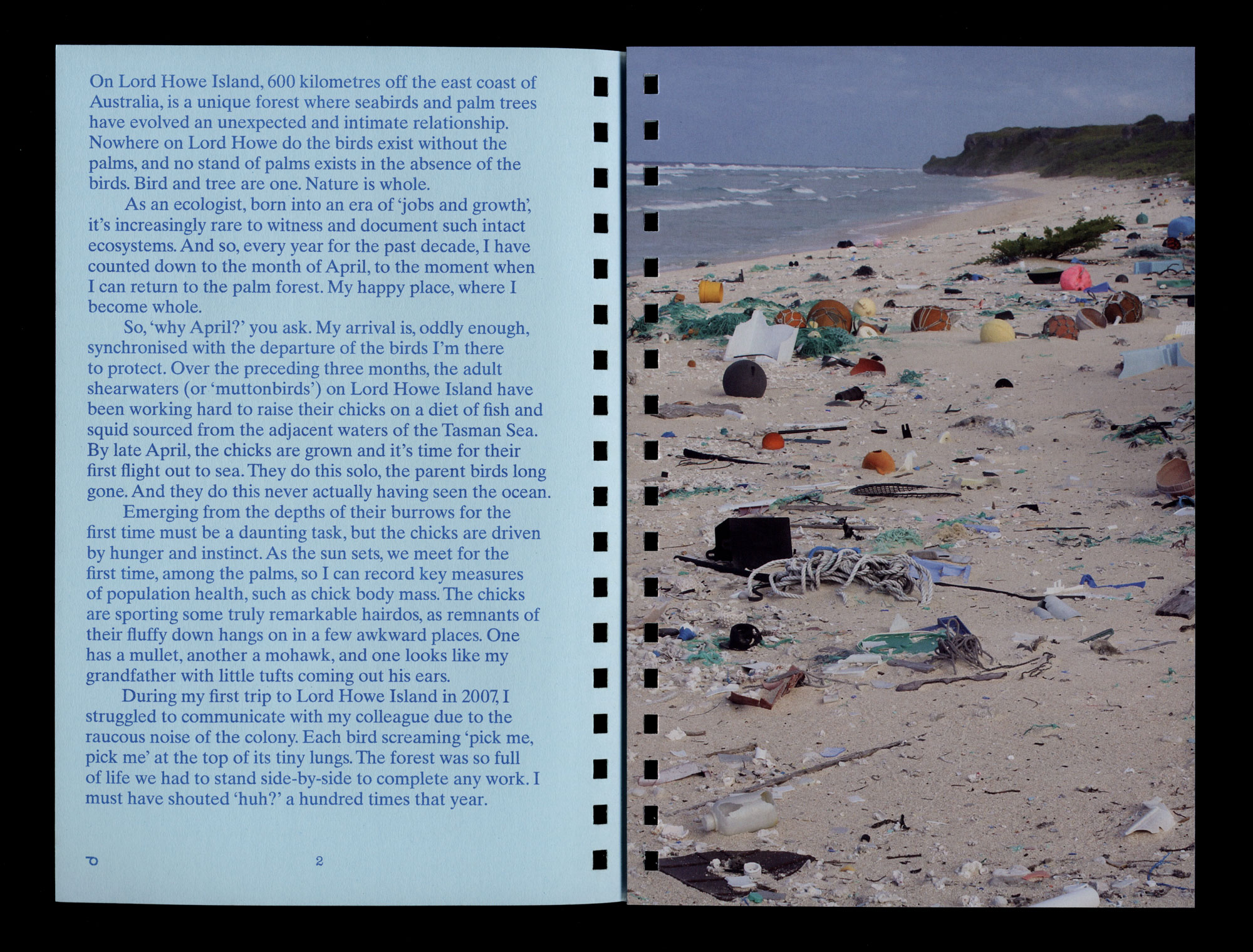

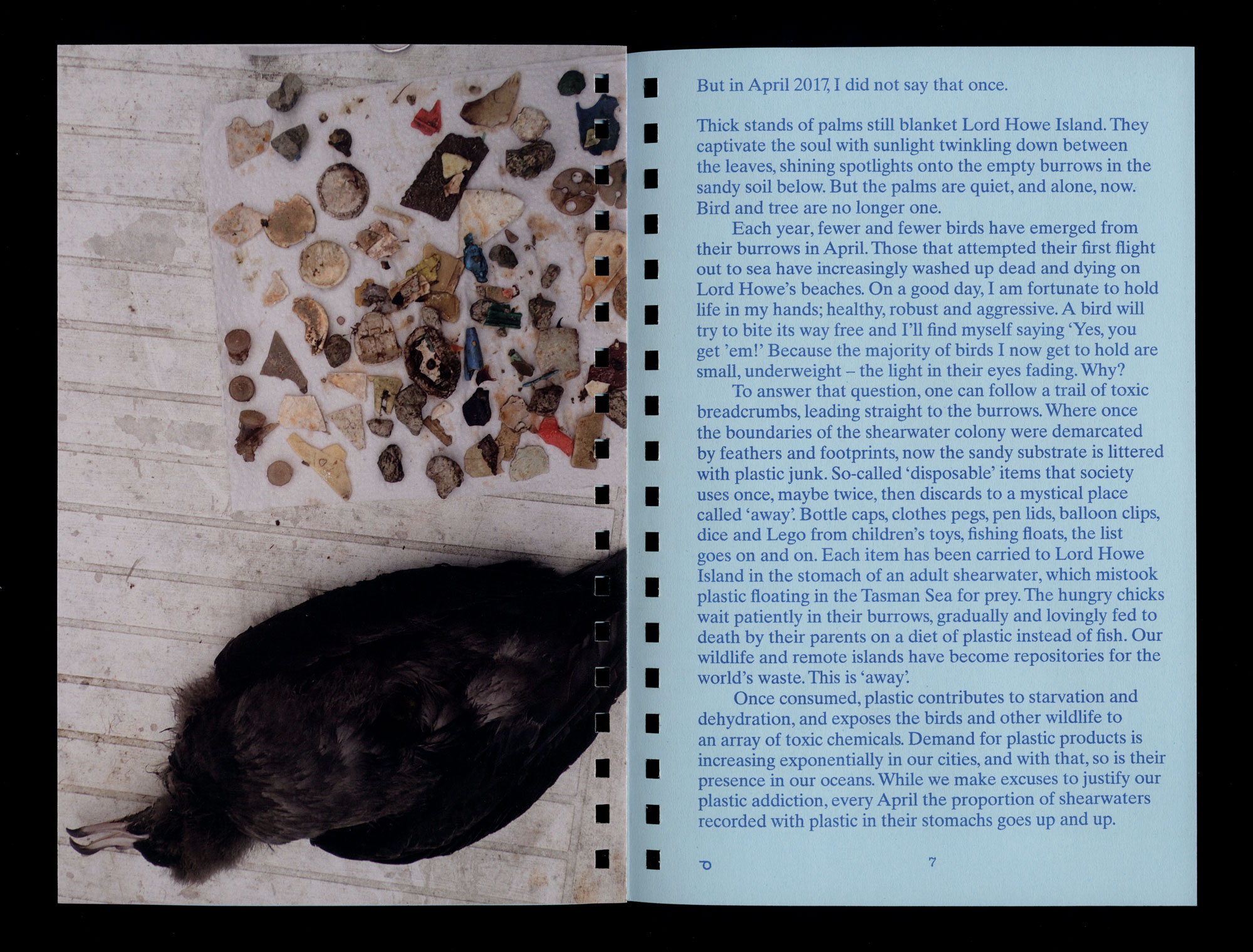

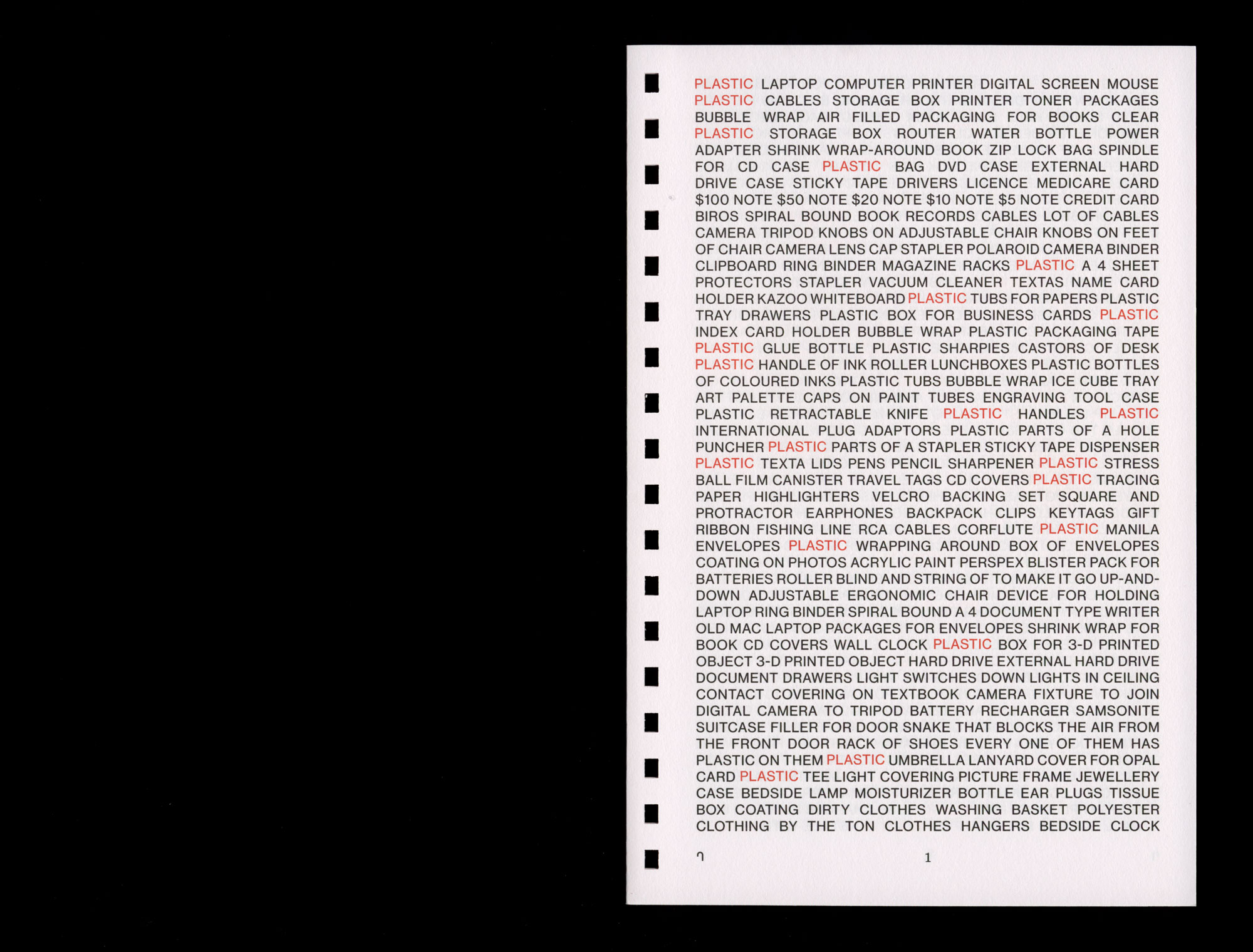

To answer that question, one can follow a trail of toxic breadcrumbs, leading straight to the burrows. Where once the boundaries of the shearwater colony were demarcated by feathers and footprints, now the sandy substrate is littered with plastic junk. So-called ‘disposable’ items that society uses once, maybe twice, then discards to a mystical place called ‘away’. Bottle caps, clothes pegs, pen lids, balloon clips, dice and Lego from children’s toys, fishing floats, the list goes on and on. Each item has been carried to Lord Howe Island in the stomach of an adult shearwater, which mistook plastic floating in the Tasman Sea for prey. The hungry chicks wait patiently in their burrows, gradually and lovingly fed to death by their parents on a diet of plastic instead of fish. Our wildlife and remote islands have become repositories for the world’s waste. This is ‘away’.

Once consumed, plastic contributes to starvation and dehydration, and exposes the birds and other wildlife to an array of toxic chemicals. Demand for plastic products is increasing exponentially in our cities, and with that, so is their presence in our oceans. While we make excuses to justify our plastic addiction, every April the proportion of shearwaters recorded with plastic in their stomachs goes up and up.

Around the globe, seabird populations are declining faster than any other bird group. Seabirds are also widely regarded as reliable sentinels of marine health. The proverbial ‘canaries in the [marine] coalmine’. So, as the quantities of plastic skyrocket and forests fall silent, a moment’s reflection: a sentinel only works when we heed the warning.

Will you listen?

This article was originally published by Everyday Futures, https://everydayfutures.com.au, and has been re-published on the Adrift Lab website, https://adriftlab.org/blog/2019/1/18/plastic-in-the-pacific. It is due to be published in an up-coming book being published by NewSouth Books, Sydney.