In consultation with Michael Jones, Norman Frank and Fabian Brown

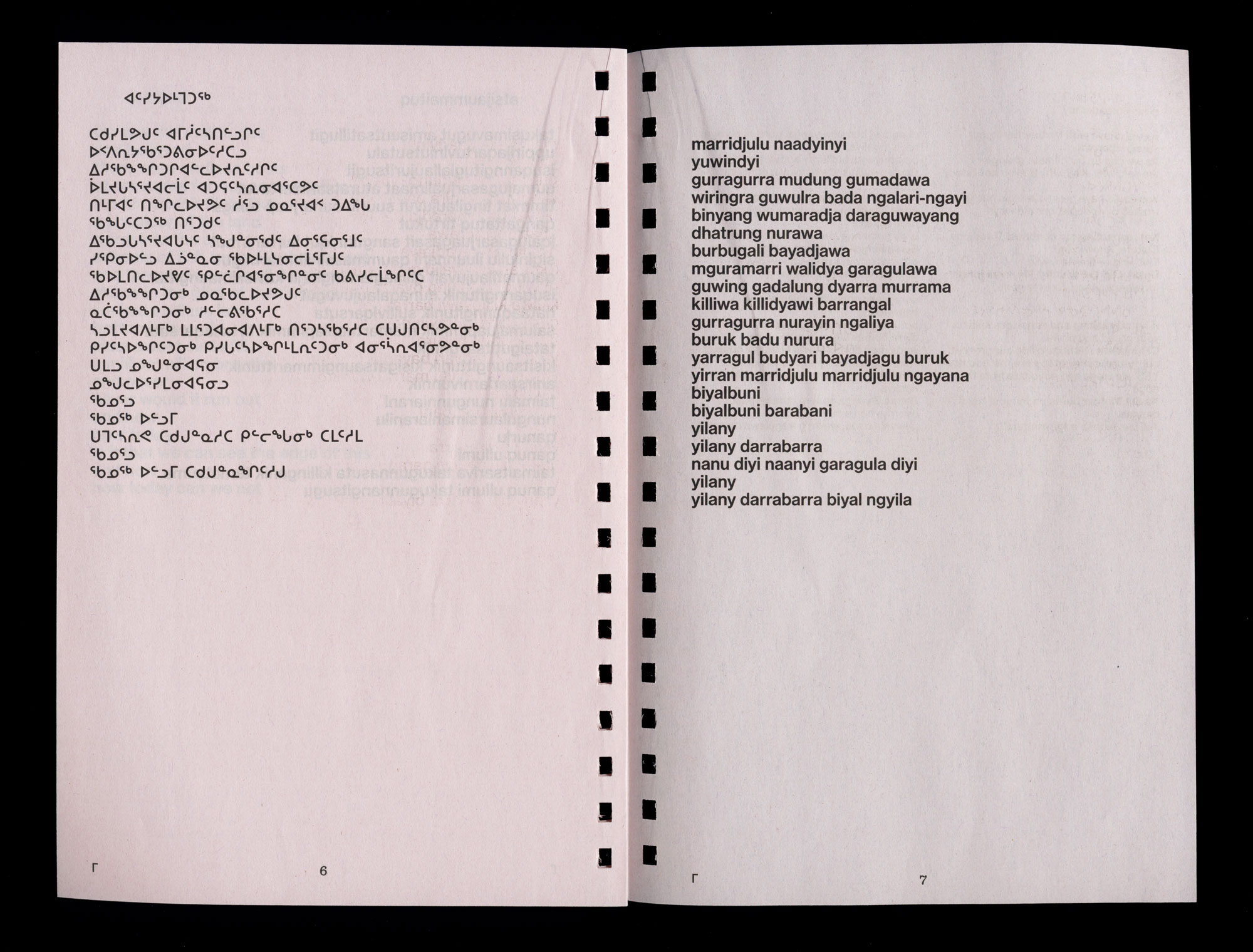

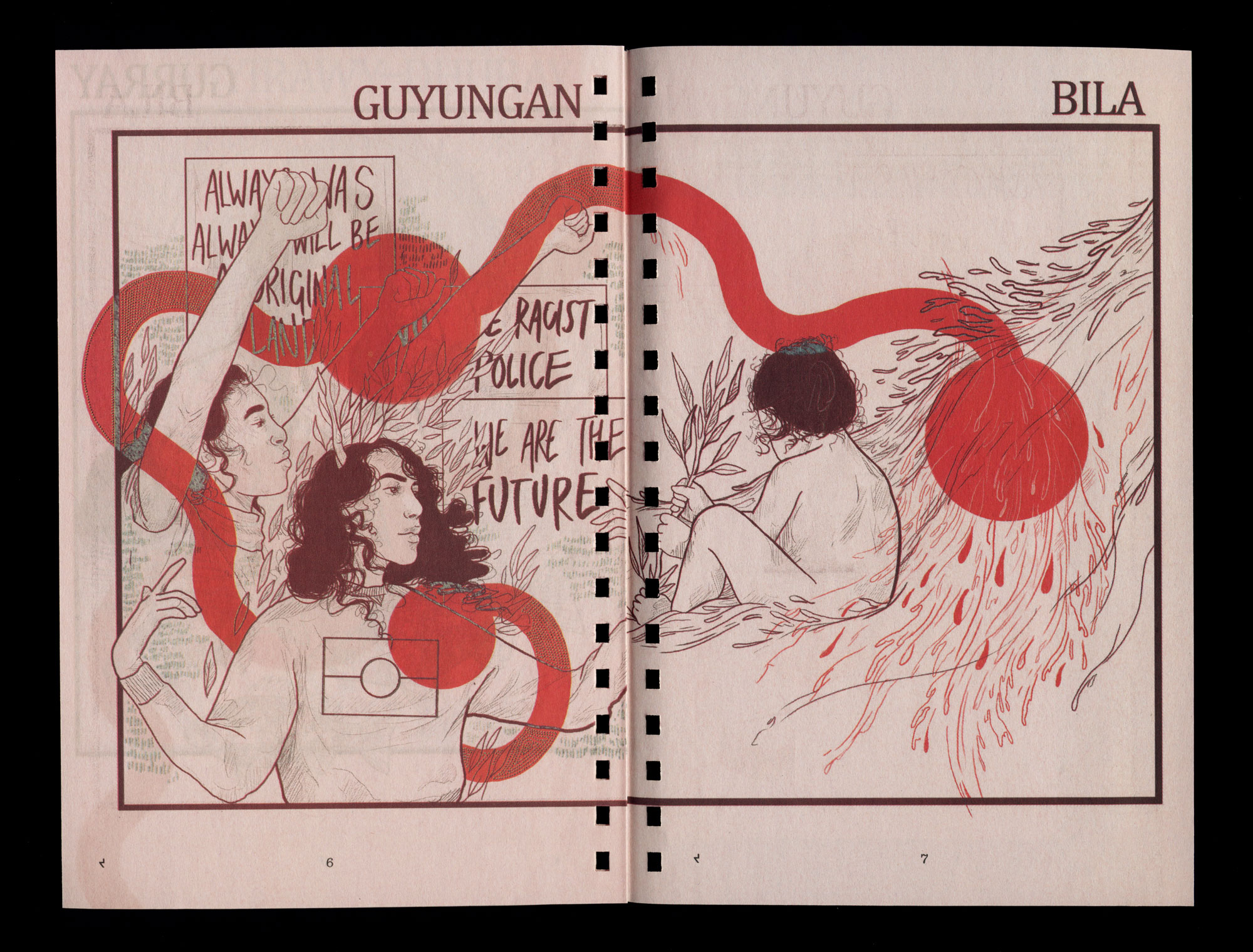

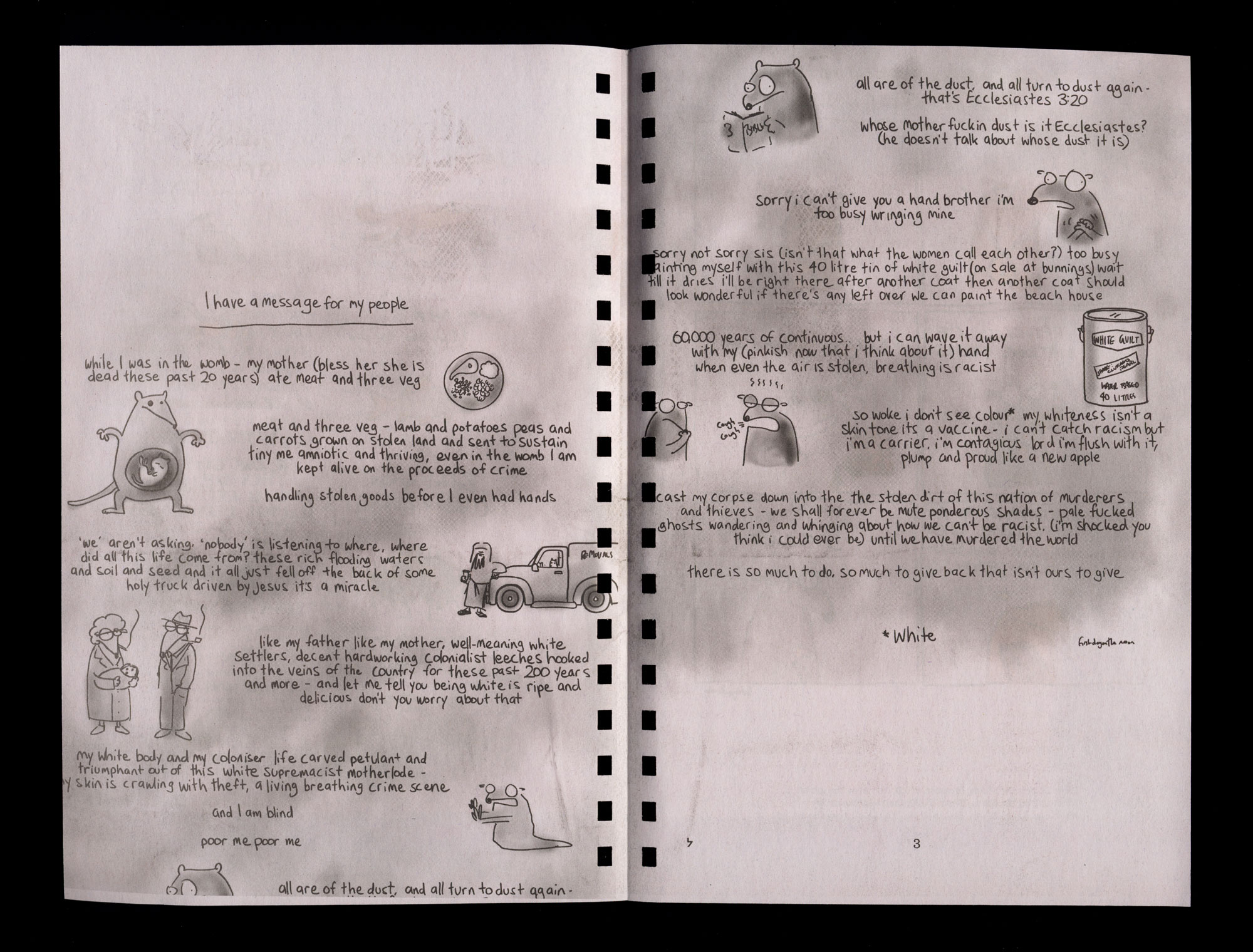

Being Mingalangala (NIRIN/the edge) can make you touchy, being Minngala ngala keeps you on high alert, you’re under surveillance and intimidation, not only by the police and society but also the watchful eye, pressure and sharp verdict of your own elders and peers – actions and words have consequences if not done properly, especially with language, or anything to do with culture or in the public eye.

Everyone can see your tracks, everyone knows your car, it’s a small enough town where everyone knows everyone.

We’re touchy buggers, our people can be hard – jukuruilpi (you gotta do it properly). Living, being NIRIN, there’s always another red flag to watch out for – worrying about the next meal, a night to get through, a fight to dodge, a rumour to wait out. We’re sensitive, many of us suffer deep wounds from injustice, denigration and disadvantage.

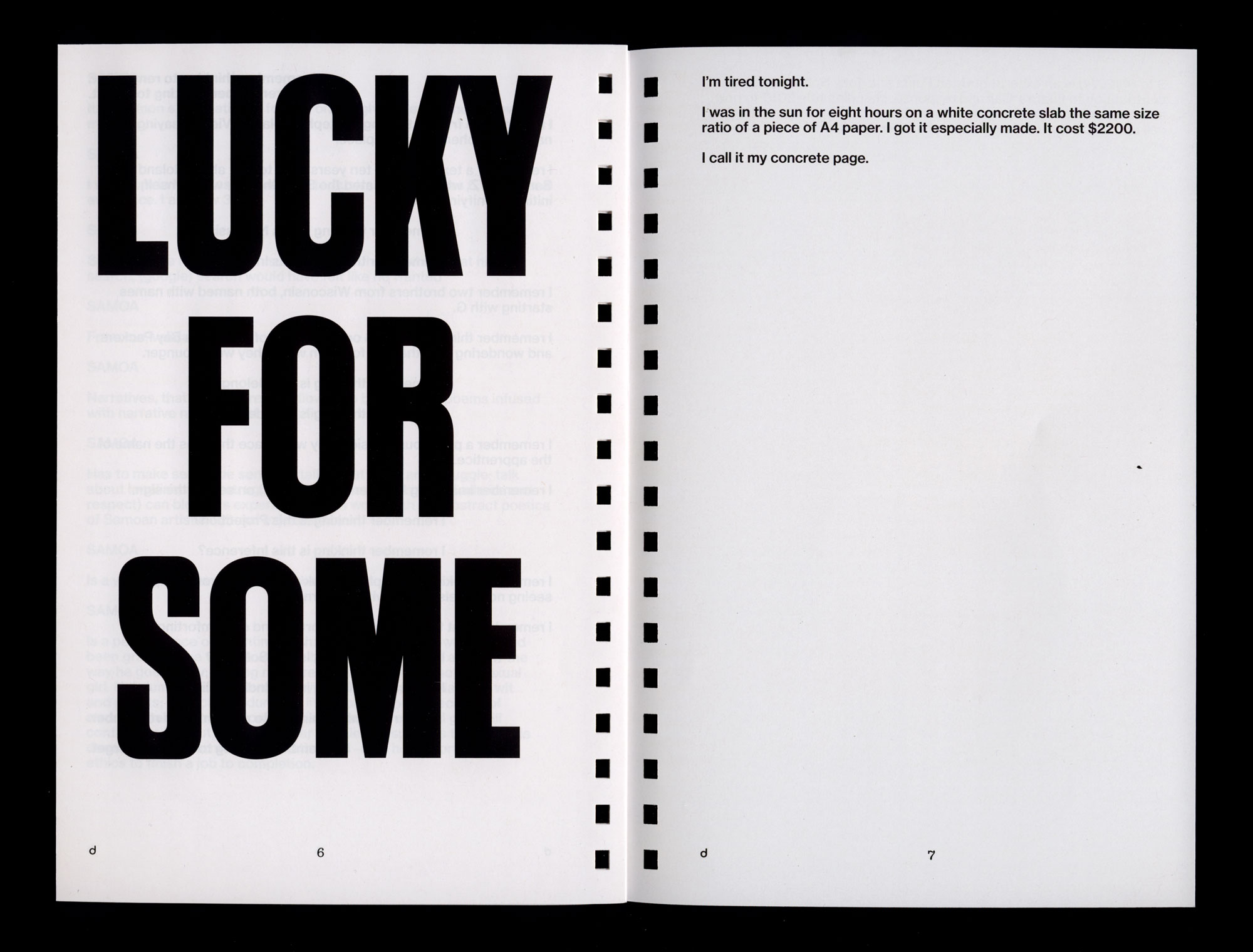

In town we are constantly anxious, we live like that in town. On country, all the stress leaves us and we are happy. But as soon as we start driving into town all that anxiety and stress comes back to us making us feel no good – we turn to family and friends for comfort but also self-medicate with substances and activities like alcohol, TV or gambling. All of which bring temporary relief, but many have consequences, like addiction, like demons.

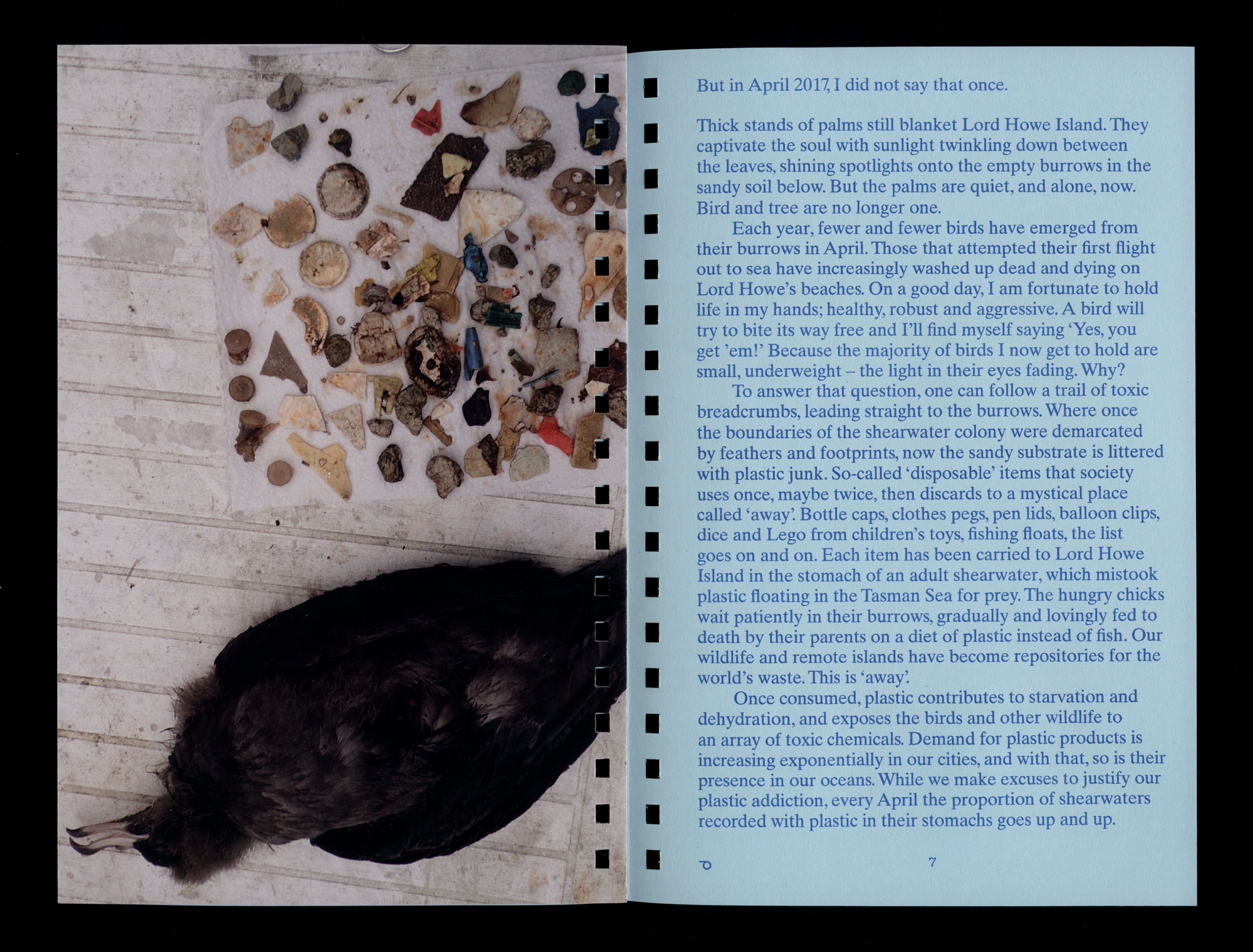

But most of all – the fear of these times – is that we are drifting away from our cultural centre – much quicker than before and we are also anxious about losing it. These things pull us away from our culture – they’ve been pulling us away for a long time but differently now. They first used the knife against us and now they have put it in our hands – to harm ourselves with. The lateral violence of internalised colonialism. First invasion and prejudice and mistreatment, taking us away from country and family, now it’s addictions and pubs … gambling away our lives and health.

We are already on the edge and especially the edge of losing everything – it’s not only our minds and bodies but our well-being, our stories, and our language. They’re saying there are only approximately 30 strong speakers left. Our culture, country, our animals and spirituality are in danger – all the things that make us strong. In the olden-days they were performing increase ceremonies to keep species ongoing. It’s a drought time now – our people have rainmakers, and now it’s drought and we want our rainmakers – we are losing them and their practices and knowledge – our knowledge is precious.

We are losing our cultural supports like our Jangkay for our men (that’s the place for mentors, right there) … we don’t have a traditional men’s shelter anymore. We used to have stronger support and guidance from our elders. Those old people used to educate the younger ones in our ways: kinship, morals and resilience, to make them into proper good strong men. From the beginning, they had a huge effect on young people’s lives. Today we are spread out but in order to stop grieving we have to acknowledge what’s happened: colonisation, massacres, stolen land, mining missions and stolen generations. We need the life forces of truth and sovereignty. We are still rubbished now even from the highest levels but we have to recognise and accept what’s happened in the past and keep fighting it now in order to move forward. We need to face and shoulder our responsibilities as men, to ourselves, our families and our community – we are still warriors in this new world.

We are the creatives and the culture men, we can travel in our dreams – Winkarra. We’ve got to go back to country for those dreams. Our country has spirits – its alive – and it needs us: ‘our spirits and country are crying for us,’ because we are not practising on our grounds. We need strong resolve.

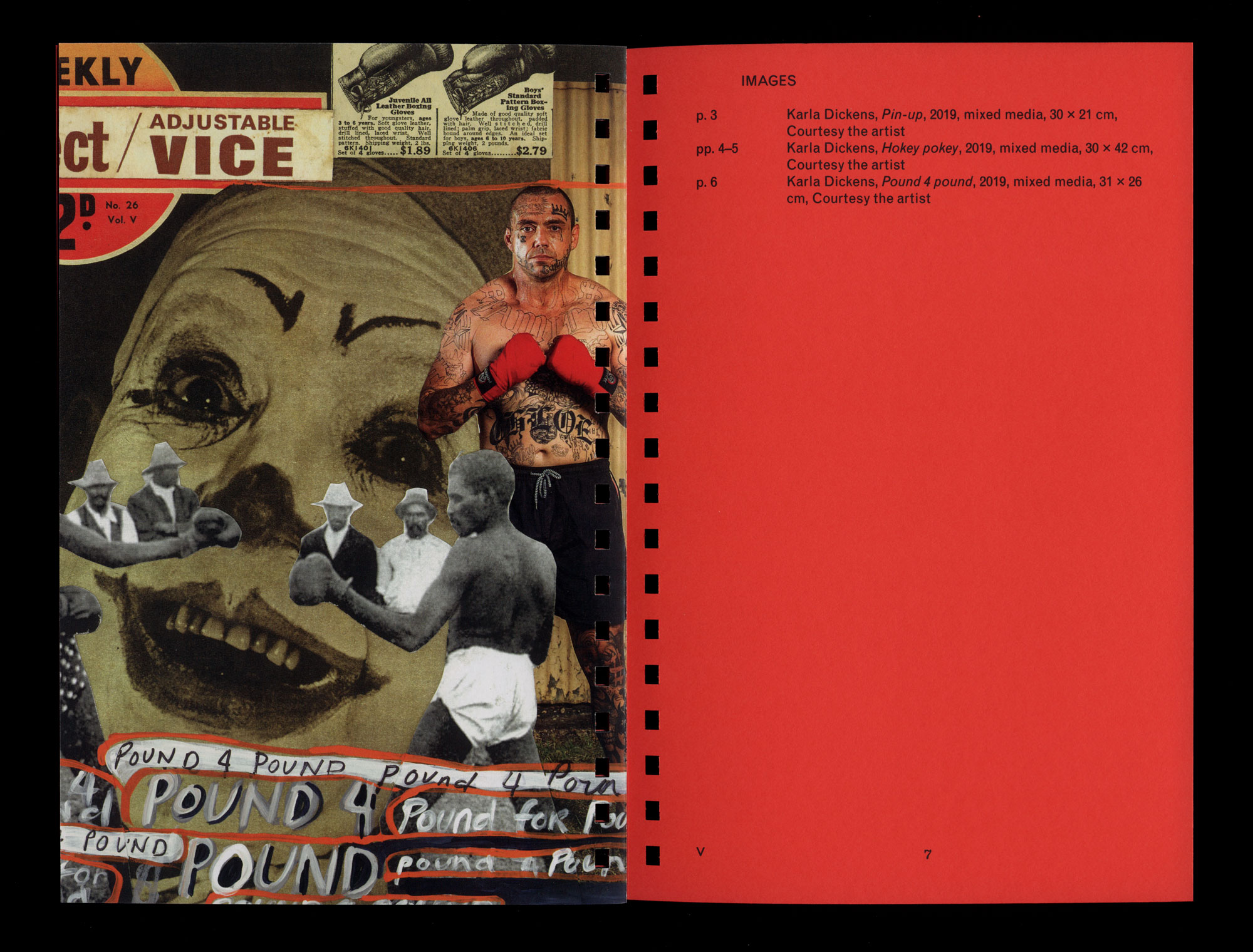

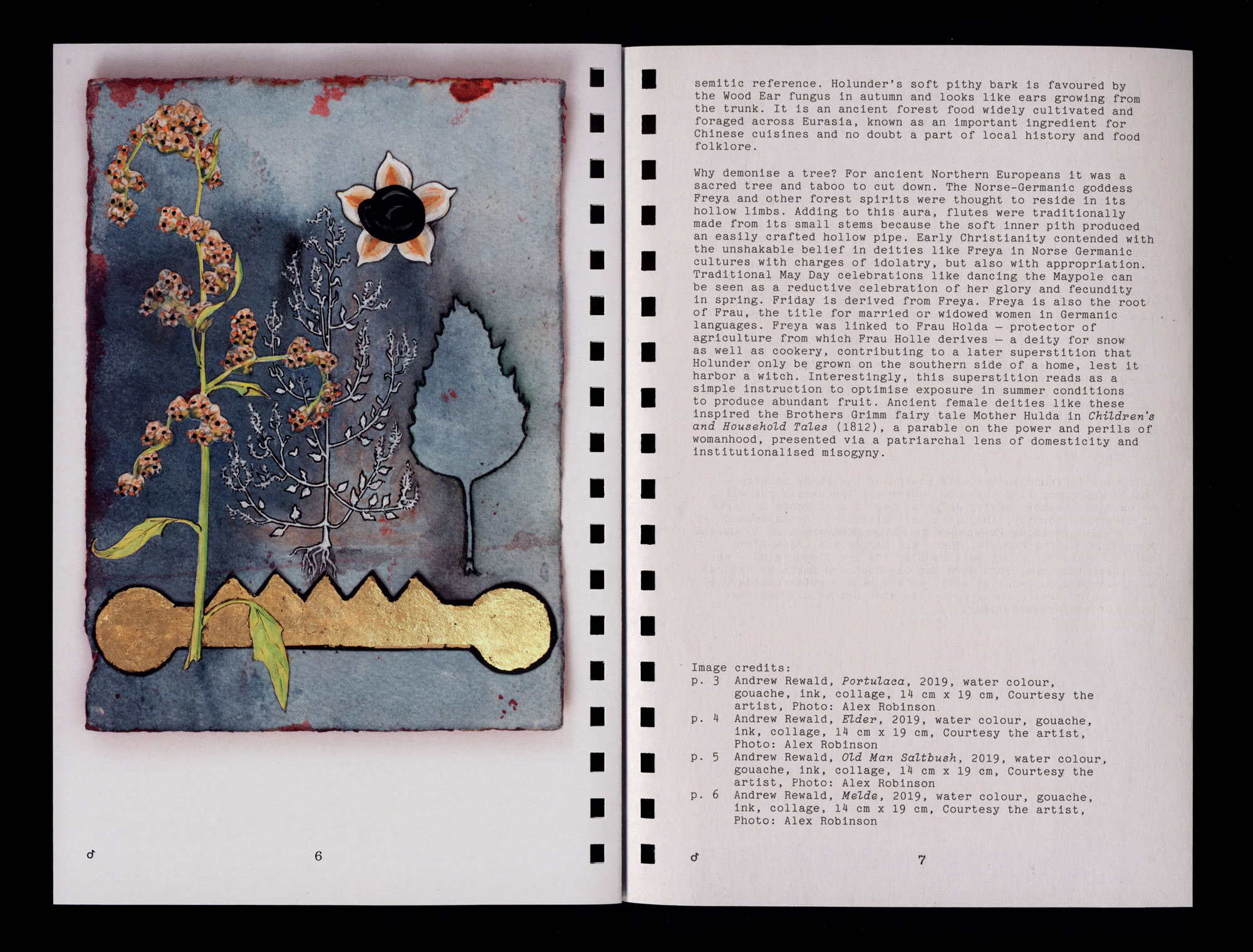

Our Art

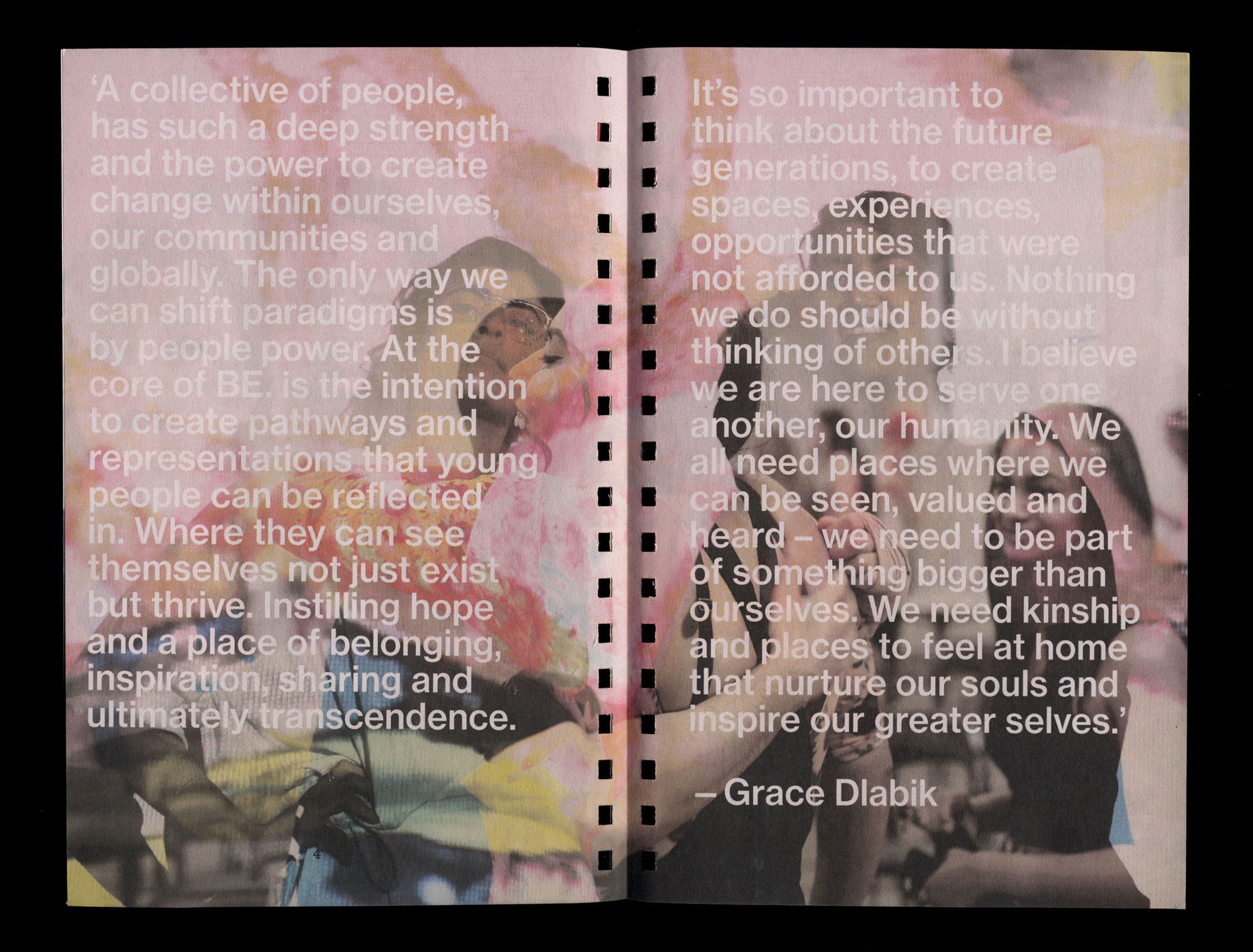

It’s a new cultural art for us mob where we can express our stories – it’s not inside our culture – it’s on the edge, coming in. Some of our dreams have different kinds of effects that come in the night, in our head, and we create something stranger. They’ve got meaning and it’s part of healing. The healing is also found in our ceremonies and our expression, it keeps people together and strong – if we lost that it would harm us and it would harm our future – if we lose it now what will we have for our future generations, they’ll never know anything, they’ll miss out on what we know.

We have our culture, our knowledge of survival, our ceremonies, our creativity, our people and most of all our country and languages.

Kamarnta wilyanka pakamarra (we are holding it strong)

Apparr Manu Ngara – Story from the Country(Country is Alive)

Joseph Williams

In consultation with Jimmy Frank and Michael Jones

Manu wankarr (old people) nyinta winkarra jangu (sing the country).

Pulkka-pulkka ajjul winanta manu.

Winkarra jja manu nyinyi Yumurlirti (long ago) Karrinyki (for the people), Pina anyul apan manukuna.

Walala Kapi (hunting/day trip) Ngurarra (camping), warrakaji anyul wangkan (talk to the country).

Wangkan manu ku, ngurramalaka, ngurramala wiparnpa nyinta manu Kuna.

Kuyu ku (to get meat), wawirri, kananganja, Wajikarr, lippriji, mukku Kapi ngarli Kunampi mukku.

Ngulya Kapi wanirri anyul wirranta, kalampi kana anyul Kankurr wanpan, alaparra manu kina anyul apan piliyi anyul nyinta.

Yawuru (happy) kapi karrinyi, kulurr janta (sad for country) manu ku kangwia kari tappu tappu kari, jutanti kari, pirlipirli kari, manu ngara pulkka pulkka pujjali punjan mangurr jangu kapi tappali yawulyu nyirrinta manu ngara.

Karrinyi ajjul karimunta ajjulunginyi manu, wangkan ajjul apparr ajulunginyi manu ngara anyul kunta puntu kapi manu kunta puntu.

Karti ajjul nyinta jangkay kana, tappali nyinta milkarnanja kana nyukartti pulka-pulka jangu

Kapi anyul kunta palanmirri (warriors).

Anyul pakamanta apparr, Warumungu, anyuku wiparnpa manu ngara pulka-pulka kari karti ajjul kuyuku appina.

Mapparnta malungku nyina ajjulunginyi walji.

Malarra malarra kapi pikka pikka milamilajinjiki apparkka.

Manu karimunjuku pinanta kangwia, kampaju, kananti, tapu-tapu, jurtanti, ngamarni wangkijikina.

Kartingki (men) kayin, wartilkirri, wijjartu, miri mukku pirrkaninta tappali (women) ji purnu kana mukku pirrkaninta kupija jangu

(This is the uncolonised story from Warumungu Country and the ways of its people)