Guarding the Space Between Us

If I were a blackbird I’d whistle and sing,

And follow the ship that my true love sails in;

High up on the main mast I’d there build my nest;

And lay there all night on his lily-white breast.1

-

These lyrics are the ones sung by my family of an English folk-song, which was first published by James Reeves as If I Was a Blackbird and described as English Traditional Verse from the Mss of S. Baring-Gould, H.E.D. Hammond & George B. Gardiner, in James Reeves, The Everlasting Circle, Heinemann, London, 1960. Many of the different versions of the song are listed here: https://mainlynorfolk.info/folk/songs/ifiwasablackbird.html ↩

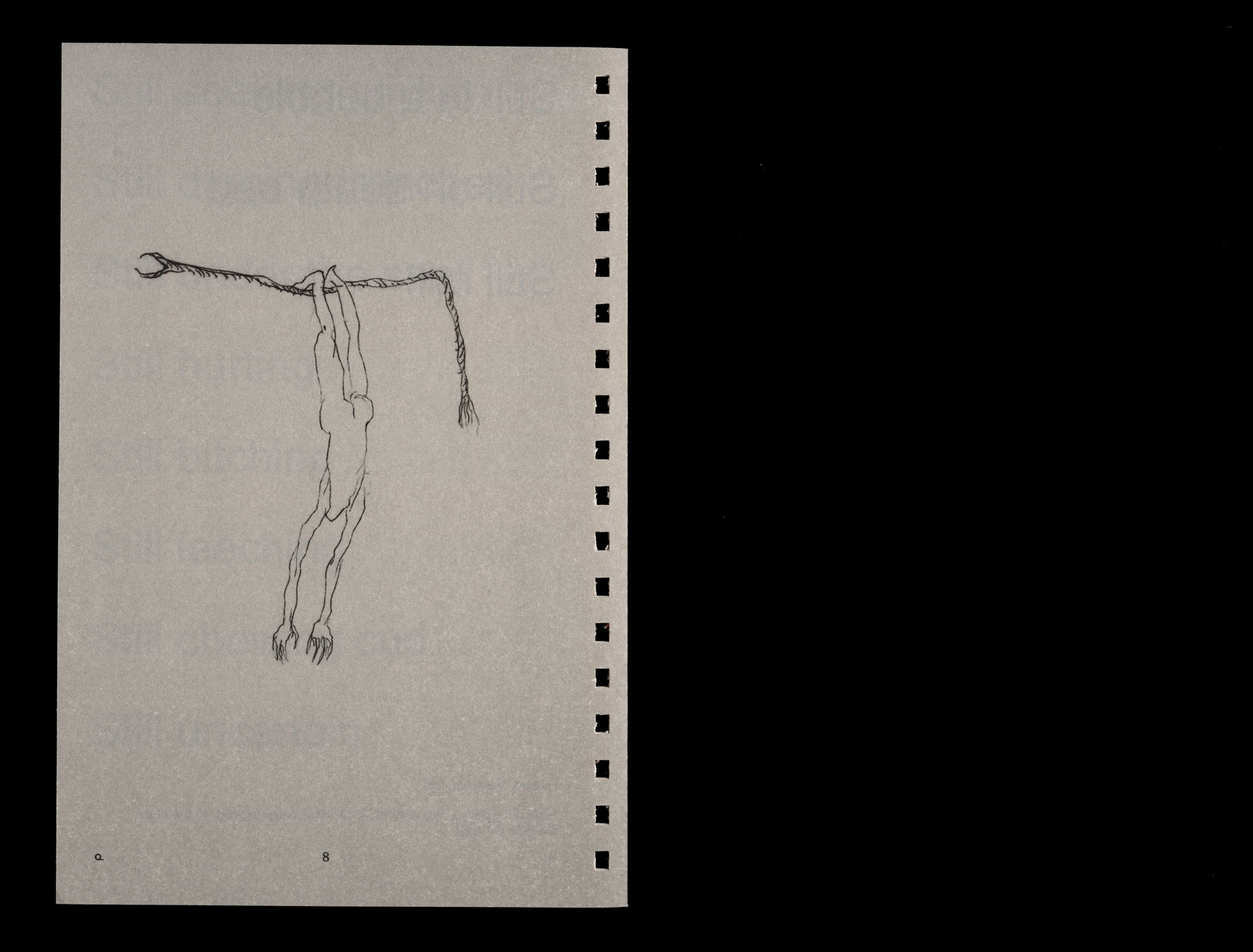

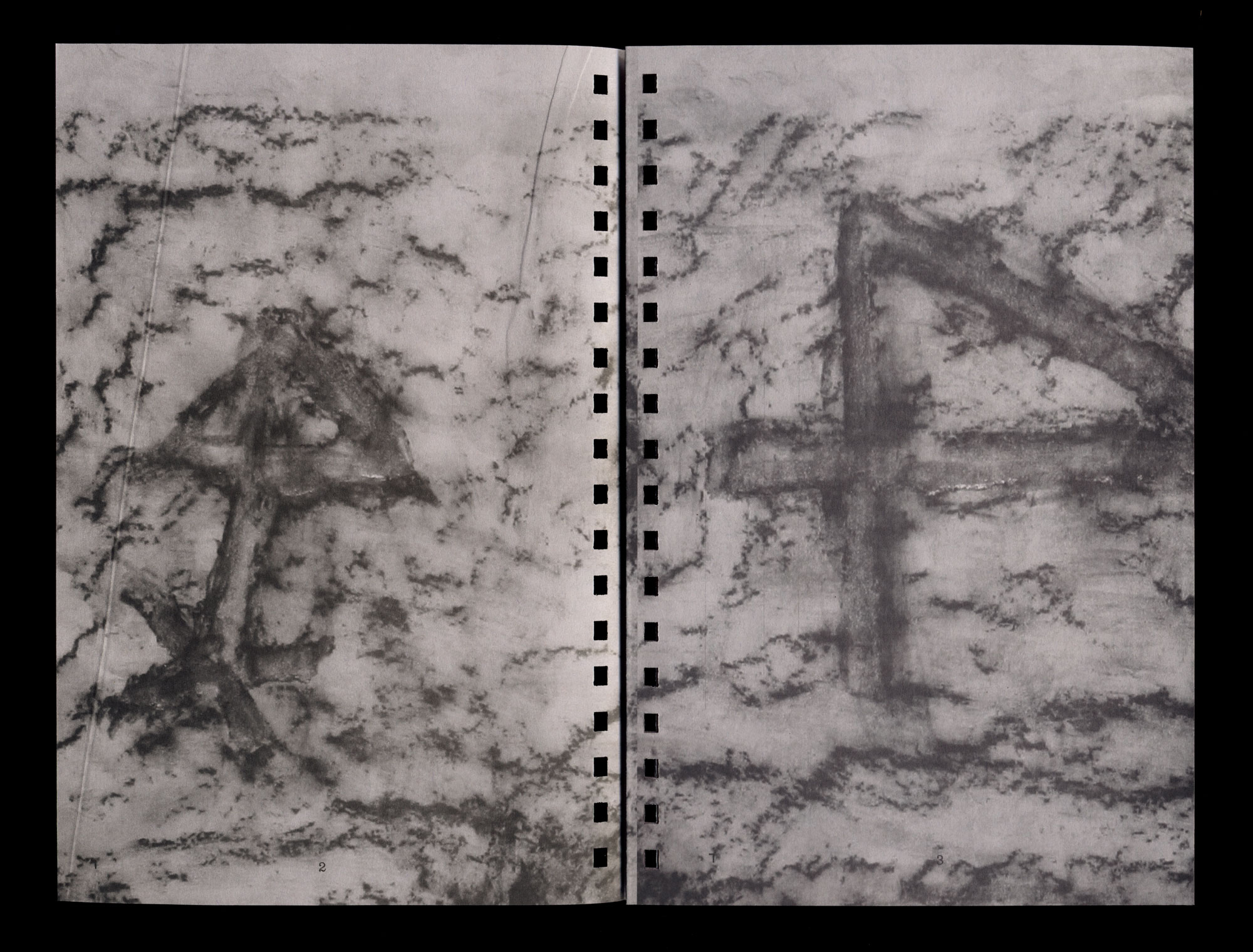

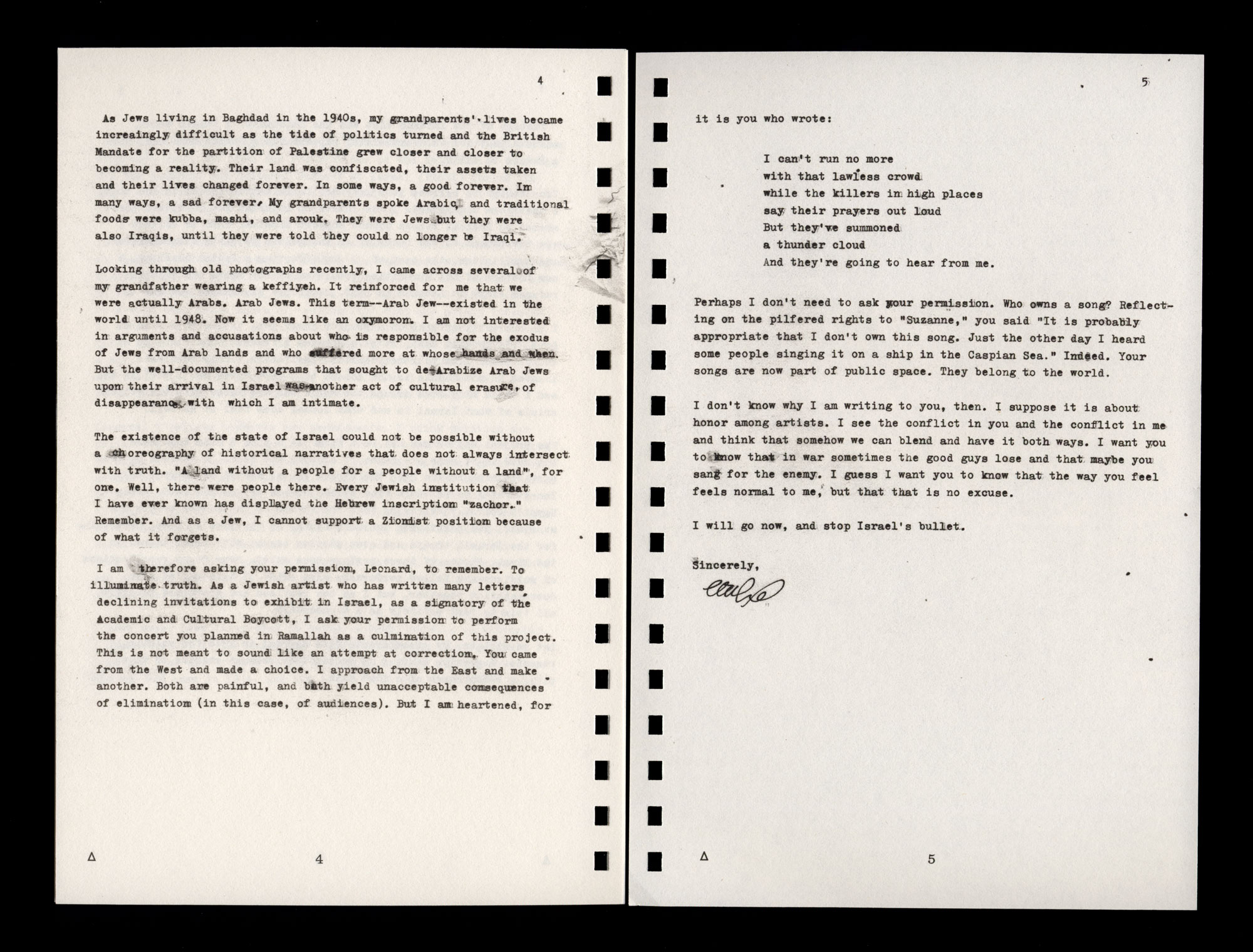

Transgenerational trauma isn’t simply passed between people across linear generations but is the deep pool from which bodies, radiating outwards and inwards, draw their grief and strength. Something like triggering – a flood of physiological responses to an instance of remembering – might be thought of as a wave form that rises high and explosively from the depths, but which returns to the same surface level, leaving the deeper contents of the pool intact. Popular culture has long been saturated with narratives of uncovering and remembering traumatic events that preference final moments of climactic discovery, psychological and physical architectures of the hidden waiting to be discovered – boxes within rooms, within rooms, within houses. Architectures of the flashback, which lead backwards and forwards to a cathartic moment of discovery and recovery. But our memories and our reactions to them can also be ever expansively present and exposed, vibrating raw surfaces that are produced and reproduced, performed and reperformed, without unsettling. I first described this as a kind of ‘everything’ that produces feelings of ‘nothing’. My friend Sam Lieblich responded that it is a ‘too much nothing’.1

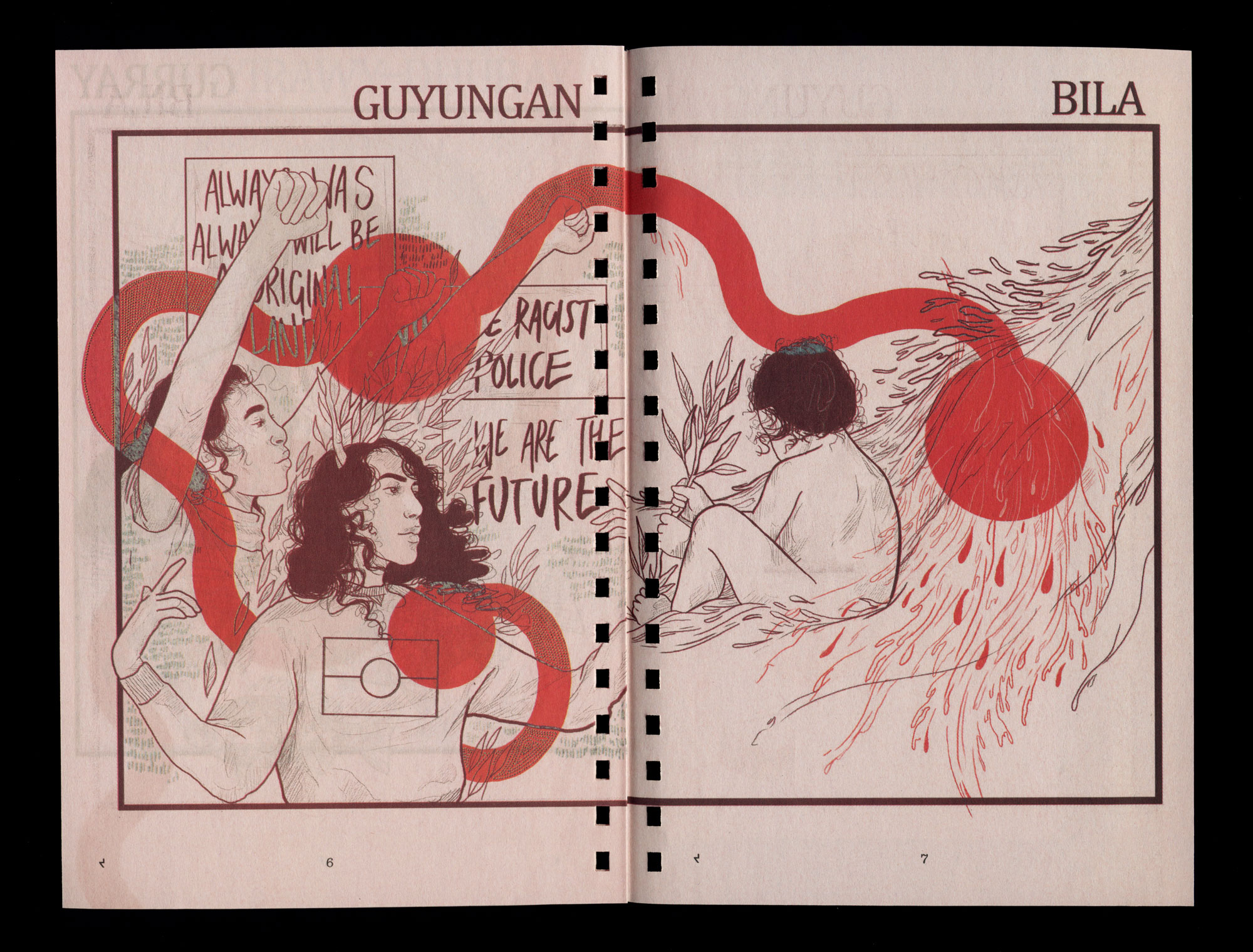

In a story, The Little Green Frog, by my grandma Gladys Milroy, a barramundi gives away his memories to a green frog in the form of stones from a waterhole, which he swims deep within to collect for his friend. Most are happy memories. The frog returns the gift with small blue flowers. Then, one day, the frog arrives to find the barramundi, ‘floating on top of the water with a black stone in his mouth and surrounded by half dead and rotting flowers.’2 When everything else is turned out the black stone becomes a poisoned weight that cannot be shared or held safely. To assume a traumatic memory is a separable dislodgeable thing creates a circular and ultimately destructive motion (diving, surfacing, drowning), whereas the smoothed black stone can also be thought of as a contiguous surface with the pool and all of the joy it holds as well. It cannot be given away. My mother, Helen Milroy, has written: ‘Healing is not just about recovering what has been lost or repairing what has been broken. It is about embracing our life force to create a new and vibrant fabric that keeps us grounded and connected, wraps us in warmth and love and gives us the joy of seeing what we have created.’3

In Paul Auster’s The Locked Room (1986) the ‘impossible crime’ suggested by the title is the ambiguous theft of an identity that is both gifted and never really discovered. The title references a genre of detective fiction where a crime is committed that should be physically impossible, the paradigmatic example being an intruder escaping a crime scene: a locked room. In Auster’s story the elusive protagonist Fanshawe, a genius writer, is slowly revealed in others’ memories as a fount of constant self-exposure and distance, intensity and withdrawal – a reluctant charismatic type whose life becomes intimately bound up with the story’s narrator, his childhood friend. This friend eventually comes to take credit for all of Fanshawe’s creative work and thinks of himself as a kind of spin-off sycophantic version of him – he inhabits Fanshawe’s life and works for him after Fanshawe leaves his wife and child and disappears. But as Fanshawe supposedly recedes from one world – only to expose more of himself more intensively in other worlds, with less familiar grounding ties to others – his moment of ‘reconnection’ to his old friend, and the climax of the story, is performed through Fanshawe speaking through a closed and locked door. Grifters, illusionists, intruders (here: mother, wife, sister, friend) have previously made it in and out of the locked room and left with debts of obligation as well as unintentional gifts (Fanshawe thinks of his intense personality as a kind of infecting force, and yet he remains plagued by being ultimately unknowable). Dave Eggers writes about the endless giving and sharing of seemingly deeply intimate stories as, ‘like the skin shed by snakes, who leave theirs for anyone to see’.4 But maybe the snake doesn’t have endless skins – thin, crumpled, packages to give – sloughing off total selves to stay fugitive. Tidal waves, heavy stones, life skins, too much nothing as disappearing acts. ‘Healing keeps us strong and gentle at the same time.’5 Be careful who picks up those skins. They may not turn to dust in their hands.

My Grandmother sings: ‘If I were a blackbird I’d whistle and sing’ and I imagine that the blackbird is a loving spirit that watches over. For us, the blackbird-crow is an ancestor spirit. But how too is the blackbird, not only a watcher or a tether to others, but also our own shadow and singer of ourselves? Who are our tethers, our shadows, our visitations, our projections and how are they us? Escaping intensities, remaining tethered, dissolving, dissembling, exposing – these are matrixed processes performed between us. We never neatly sit on one side of the exchange. Negotiating our multiplicities across the borders of others: who flies above the ship that navigates the surface of the depths; who sleeps on its deck; who slips below? Sighted from above, a head on a chest in the night. How to be close to others and remain safe. How to remain safe and be close to others. To follow without being pulled under, always with the ability to fly away when the waves rise up, connection that is a dance of oscillating autonomies and entanglements. Flee the ones we love, return to them, keep watch.

-

Dr. Samuel Lieblich, a psychiatrist and Lacanian, provided notes on this piece, and also suggested the title: ‘Guarding the Space Between Us.’ ↩

-

Gladys Milroy, ‘A Reflective Story by Gladys Milroy – The Little Green Frog’, in Pat Dudgeon, Helen Milroy and Roz Walker (eds), Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd Edition, 2014, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, xix–xxi, available at: https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/working-together-aboriginal-and-wellbeing-2014.pdf ↩

-

Helen Milroy quoted in Tamara Mackean, ‘A healed and healthy country: understanding healing for Indigenous Australians’, The Medical Journal of Australia (MJA), 2009; 190 (10), pp. 522–523. ↩

-

Dave Eggers, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2000, p. 215. ↩

-

Op. cit. Helen Milroy. ↩

The Black Feather

Gladys Milroy

Passing on Living Knowledge

Wombat was Dingo’s best friend. Moon was his second-best friend, who he talked to every night. Wombat knew everything. Everyone went to Wombat for advice. ‘Why do you know everything Wombat?’, Dingo asked. ‘I went to school under the Learning Tree’, Wombat said. ‘My grandfather and his friend Black Crow taught all the children. Every day we sat under the Learning Tree where my grandfather lived in his burrow. The Learning Tree was full of large blackberries and Black Crow would pick a berry and drop it onto the ground. Then grandfather would tell us the learning story of each berry that was taken from the Learning Tree. Eventually I thought I had learned everything and was as good as my grandfather, so I said goodbye. ‘You learn all your life grandson’, grandad said. ‘Maybe it is time for you to find knowledge on your own.’

Wombat set off very proud of his knowledge, telling all the animals he met how clever he was, and that he knew everything. One day he was sitting by a rock pool talking to a little frog who lived there. ‘Why do you think you know everything Wombat?’, Frog asked. ‘I went to school’, Wombat replied. ‘But you can’t jump like us!’ Frog laughed, jumping into the rock pool. ‘Silly Frog’, thought Wombat.

Wombat felt so tired, he had been away a long-time, and for all his knowledge, he had no friends. He heard someone call his name. It was Black Crow, looking very old. ‘Time to come home Wombat’, he said, ‘your grandfather needs you.’ Crow flew away and Wombat hurried back home. When he arrived, he was shocked to see the Learning Tree was old and bent-over. No lovely blackberries covered its branches, no children sat on the ground, it was sad and empty. He saw Old Crow. ‘Where is my grandfather?’, he said. ‘What’s happened?’ ‘When you left Wombat, one by one the children stopped coming, until no-one came. Your grandfather was heartbroken. No-one wanted to learn the old stories anymore. He went to his burrow under the Learning Tree and never came out.’ Wombat started to cry, ‘Thank you Crow for looking after my grandfather.’ He glanced up at Crow’s nest in the Learning Tree. In it was only a broken old nest with a single black feather lying there.