for Dean and the Green Cape Gurandgi

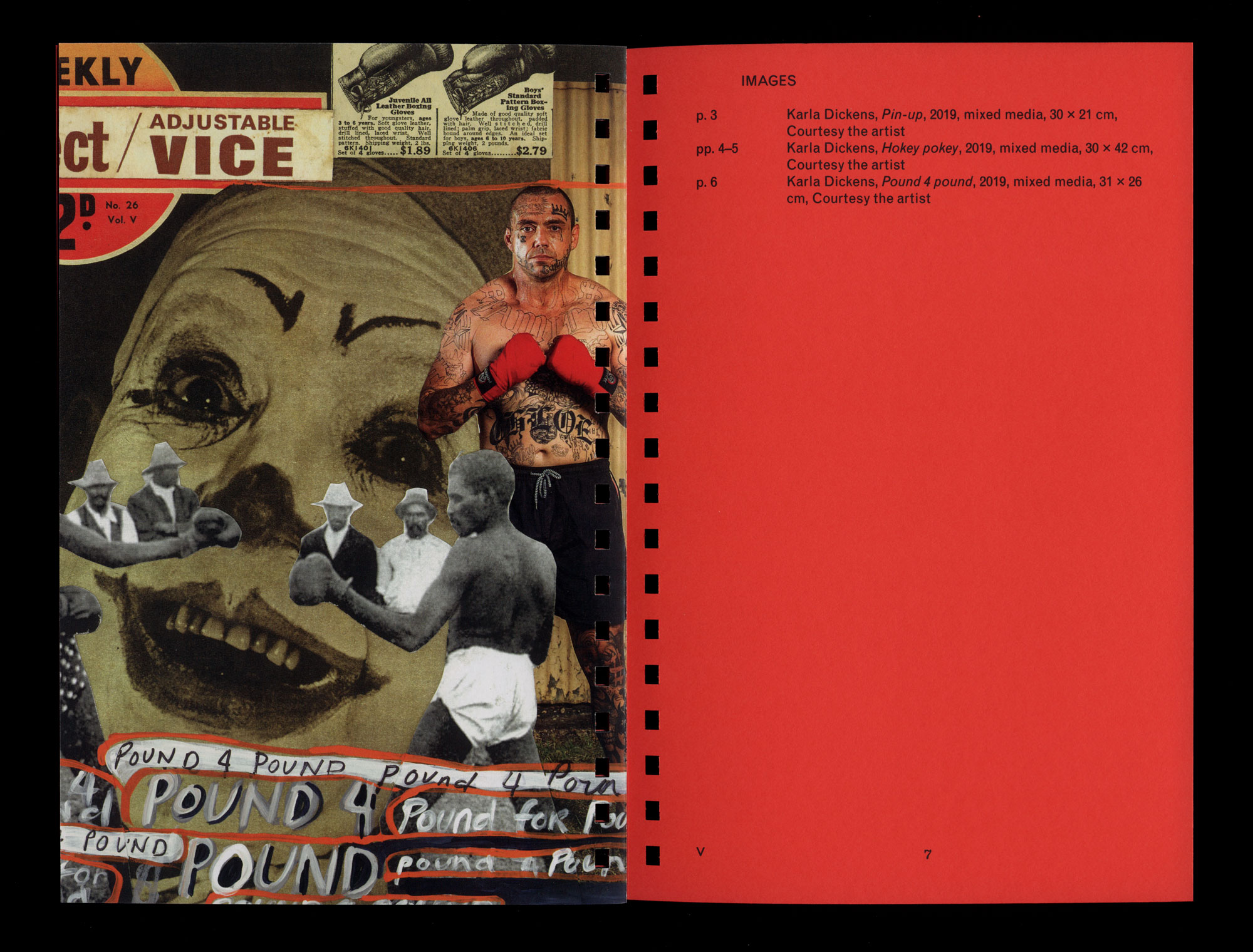

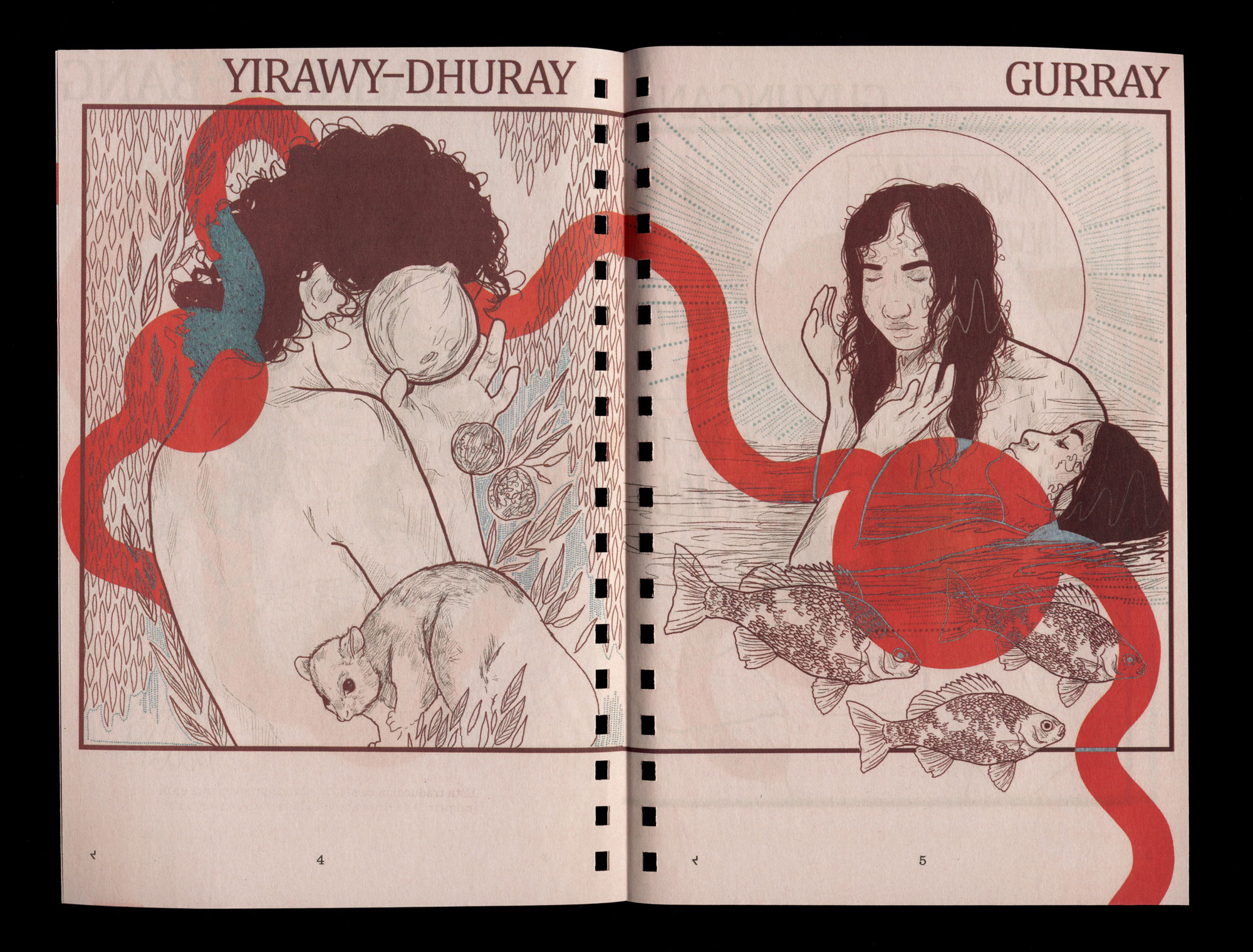

Four Aboriginal men are swimming. Hunting to feed their camp.

There is a cleft in the shore where a bastion of stone guards a channel, sheltering it from the pounding sea. The boom of the breaking waves can be felt as a dull reverberation in the stone, one hundred metres from where the surf explodes. A detonation through the earth itself.

But the earth is protecting with a long, loving arm, a jade sanctuary where fish idle and seaweeds wave with an indolence defying the violence of the ocean on the seaward side of their guardian.

The men bring up walcun, abalone, from the clefts in this idyllic pool of sanctuary. Urchins and cockles are teased from the same clefts, the twine bags beginning to bulge with the harvest.

It is winter and the water is cold but the sun shines so the men stretch on the rocks, absorbing the heat transferred from their grandfather, the sun. They doze and yarn with wry self-deprecation. They are at work but loving it, full of pride that everything they do has a protocol in lore, a purpose in life. They sing about the sea and their feet jaunt to the steps of the ceremony they will perform later that night.

The surge of the violence, crashing on the guardian eighty metres away, causes the water of this mild jade basin to lick at their toes, causing them to lift their feet clear of the coldness, so as to prolong the exposure to the warmth of the sun, before venturing into the sea for one last harvest and the return to the camp.

The pool is jade, you could say, but more truly it is glassy green and the gentle sway of the weeds – ginger, brown, cream, blue, green – is a gentle pulse, mesmerising. The men might be at work but they are lulled by the dreaming of the sea.

One lifts a walcun from the rock and disturbs a crab that crabs away indignantly in sideways chagrin. He can feel the smile on his face even while submerged two metres below the surface of gadu, the sea. He wonders at the peculiarity of smiling underwater, at finding a crab amusing, at floating and gliding while at work.

Eventually the swimmers pick up their bags of fish and hop and step across the broken reef with a sharp eye for treasure. There is a vein of dark rock deep in the sea and far to the south. The massive kelp beds of Bass Strait are heaved about by the ocean and sometimes wrench a clout of rock from the sea floor where they are anchored. The kelp floats it in to shore and there it provides the perfect stone for the people to knap sharp blades.

There are other cobbles of stone from other subsea sources and some are veined with pure white, which, against the black rock, is very beautiful and prized by the men for making stone axes. One man exclaims as he finds a piece and declares that he will make a special axe for his uncle, to honour him and praise him.

They laugh and chatter as they walk, thrilled at the good things they can bring back to their camp.

One of the men detaches himself after removing urchins from the bag and he splits them, lifting out the segments of roe and washing them in a still pool of ocean brine. He holds out the morsels to his brothers and they tilt their heads back and let the urchin roe pass across their tongues. The salty cream causes their eyes to close in delectation of the sea.

In a deeper pool where a surge introduces water in quiet floods, a mild and somnolent echo of the violence beyond the reef, they shuck the walcun and remove the fat flesh. They shuck enough to lighten their load and others they leave whole so they can be broiled in their shells.

On the point of discarding the shells back into the sea, where sweep and wrasse will browse on the gut, they notice one shell has a small flat blister pearl. The whole shell is a rainbow of nacre, but this small jewel is dark midnight blue and green, a dark and secretive opal. This man, Naadjba, has seen them before, but this is the first he has found one himself, and he is spellbound, turning it in his hands, wondering if the one to whom he will gift it will lift her face to his and smile. He wants that smile, his whole body craves it, thrills to the thought of that sun on his face.

He is just a man and a man is sensitive to the slightest encouragement. Men, they are fools to their senses but can also be driven to dignity by it. When at their best. And truly their decency is what they crave.

The bags are hoisted and they begin the walk to the base of the cliff but their eyes miss nothing. They notice the lightning flash of the mullet, the clownish angled creep of the crab just a metre from the surf, the gull rocking and angling into the wind – its own eye gimlet sharp for small fish.

Suddenly a cry goes up from one of the men, Guruwul, the whale, breeches only a few hundred metres from where they stand.

‘Guruwul, Guruwul’, they cry. Further out to sea, the spouts of another twenty whales vent as plumes before their breath drifts as haze in the cold ocean air.

The men watch carefully because the whales are going north not south. They watch until the whales resume their southerly journey to Antarctic waters. They have been circling to teach their calves how to swim and feed, one more crucial strategy of survival.

It is fortunate that the men have Jeela with them, one of their most respected songmen, and they sing their song for Guruwul. Wirrangun doo ma doogia barwang. Clap sticks appear from nowhere, red bands are plucked from wrists and their song is energetic, hopeful and, most of all, thrumming with respect.

It has been a magnificent day and their spirits bubble up and joy splits their faces into grins. They are proud and humbled all at the same time, warmed by their spirit and the winter sun of their great southern land.

The bags are lifted, the knives sheathed in waist bands, the pearl secured a little lower and the journey begins to the valley where they will be greeted by their clan, welcoming their safe return and the delicacies in their bags.

It is a wonderful day and it is Wednesday, September 16th, 2019.