Este texto surge de una conversación realizada en 2016 en Quechurehue o Kechurewe, en el contexto de la investigación y colaboración del proyecto Fence (2017) del artista Olaf Holzapfel, como parte de Documenta 14. Con motivo de la 22ª Bienal de Sydney, Paz Guevara y Elicura Chihuailaf se reunieron nuevamente en 2019 en Madrid para editar y añadir

a la conversación.

Paz Guevera (P):

Usted se refiere a un mundo que no es centrado en el ser humano. Como usted ha escrito: ‘las historias de árboles y piedras que dialogan entre sí con los animales y con la gente’ (Sueño Azul, 1995) o ‘Las piedras tienen espíritu, dice nuestra Gente / por eso no hay que olvidarse de Conversar con ellas’ (Sueños de Luna Azul, 2008). Por ejemplo, qué historias cuentan las piedras o los árboles para entender esta cosmovisión que no es centrada en el ser humano ?

Elicura Chihuailaf (E):

Le respondo aludiendo al punto desde el cual surge esta idea. Hay un concepto en mapuzugun o mapudungun que es Itrofill mogen o Itrofilmongen que significa ‘biodiversidad’. Si describimos este concepto, significa la totalidad sin exclusión, la integridad sin fragmentación de la vida, de todo lo viviente. Es el concepto fundamental de la visión de mundo mapuche.

Un ser humano, un ser vivo, una piedra –aparentemente inanimada– pertenece a un lugar y tiene un ngen / un espíritu. Pertenece a un espacio que es tan importante como para el ser humano, porque lo comparte con él y hay por ello una relación de reciprocidad, de interdependencia. De ahí la totalidad sin exclusión y sin fragmentación.

Es en esa perspectiva que nuestra gente dice que ninguna persona elige nacer en un color, en una forma física determinada, en un idioma, en una visión de mundo, en una historia, en un territorio determinado, pero tenemos -nos dicen-, una Tarea: conocer lo que nos ha tocado. Y por lo tanto, conocer el espacio físico de los seres vivos y de todos aquellos que están situados en el mismo territorio con su correspondiente infinito. En mapuzugun se dice Tuwvn, que es el espacio físico en el que vive la familia. Kvpan, que corresponde a la familia / rukañma de cada cual. Kvpalme, que corresponde a la comunidad / lof de la que es integrante la familia; el entorno humano y vivo, la totalidad que pertenece a esa comunidad. El ritual vinculante de todo esto es el Nvtram / el Conversar; la Conversación / Nvtramkan. Porque para conocer la conversación es lo más importante. Conocer es -dicen- la única posibilidad de amar aquello que nos ha tocado y, por ende, alcanzar ternura por nosotros mismos.

Si nos queremos podemos comprender que la diversidad es extraordinariamente valiosa y que es imprescindible escuchar las conversaciones de la gente, las conversaciones de la Tierra (la naturaleza), las conversaciones del universo que habitamos y nos habita. Ello significa tener siempre en cuenta el círculo de la memoria (que es presente porque es pasado y futuro al mismo tiempo): silencio, contemplación, creación. La conversación es creación que se sostiene en las voces – el pensamiento – de los antepasados que hablan porque viven en nosotros. La Conversación es un arte en el que lo más difícil no es aprender a hilvanar nuestros pensamientos, lo más difícil es aprender a Escuchar.

Escuchar -nos están diciendo- la conversación de los árboles, no solo lo que nos comunican, sino también su diálogo con otros árboles, para además comprender el cómo se relacionan entre ellos (la cotidianidad del bosque). Cuando – por ejemplo – sopla el viento, no todos los árboles se mueven de igual manera. Aquí, en esta zona de Cunco y del lago Kolico, es frecuente el viento puelche. Puelche significa: ‘como gente que viene del oriente, del este’, desde la cordillera de Los Andes, porque cuando sopla las copas de los árboles oscilan como cabezas de personas caminando. Como sabemos, la acción de caminar del ser humano tiene características similares pero cada uno tiene una cadencia particular, influenciada incluso por la pertenencia cultural. Lo mismo sucede con las familias arbóreas: coigües, hualles, robles, álamos o encinos, etcétera ..., que al ser movidas por el viento cada cual tiene también una cadencia propia.

Entonces, los árboles y el bosque nos están hablando asimismo del territorio y de la historia que les ha tocado; del aire, del agua y del clima que los ha rodeado. Porque – desde luego – no es lo mismo habitar en las colinas de la precordillera de Kechurewe que habitar en las cumbres de la cordillera que está próxima a nuestro territorio. Si, por ejemplo, aquí observamos las hojas de los árboles nativos veremos que en la mayoría de las especies las hojas son anchas y cóncavas, o sea, están preparadas para recibir el agua y el abundante rocío en casi todas las estaciones … En invierno en nuestra comunidad también cae nieve, mas no como en la cordillera donde es muy frecuente, por eso allí las hojas -anchas o finas- son planas y aguzadas, lo que permite que la nieve escurra fácilmente y además permite a los árboles resistir mejor la fuerza del constante viento. Así, una hoja nos cuenta de dónde viene, a qué lugar pertenece … Por consiguiente si observamos las piedras, no es igual la conversación de una piedra que procede del cauce de un estero, que vemos y palpamos pulimentada por el agua, a otra que procede de una superficie expuesta al sol, al viento o a la nieve, con diversos grados de porosidad, ondas y rugosidades.

Los seres humanos hemos ido perdiendo la capacidad de comprender el idioma de la Tierra, la conversación del espíritu de la Naturaleza; hemos ido olvidando que todos los seres y todas las cosas tienen un espíritu, y que las palabras resuenan también en el tiempo y vigilan y sueñan en nuestro espíritu. Todo lo que aprendemos y conversamos tiene que ver con lo cotidiano y a la vez con lo trascendente e infinito, porque nuestro espíritu – nos dijeron nuestros abuelos y nuestros padres – viene desde el oriente, del lado donde se levantan la Luna y Sol. Viene desde el Azul más prístino, no de cualquier azul. Esa es la energía que llega a habitar su casa transitoria que es nuestro cuerpo y que – así como nosotros en la infancia habitamos la casa de nuestros padres – después se va, continúa su camino en el círculo de la vida. Sigue su andar – su vuelo – hacia el poniente, cruza el Río de las Lágrimas y retorna a su lugar de origen, al misterio del Azul profundo e infinito.

P:

Usted ha escrito que la memoria puede guardarse en los tejidos y los símbolos de sus dibujos, ‘El contenido de los dibujos que hablaban de la creación y resurgimiento del mundo mapuche de fuerzas protectoras, de volcanes de flores y aves’ (Sueño Azul, 1995). Qué símbolos podemos interpretar en los tejidos donde se guarda la memoria?

E:

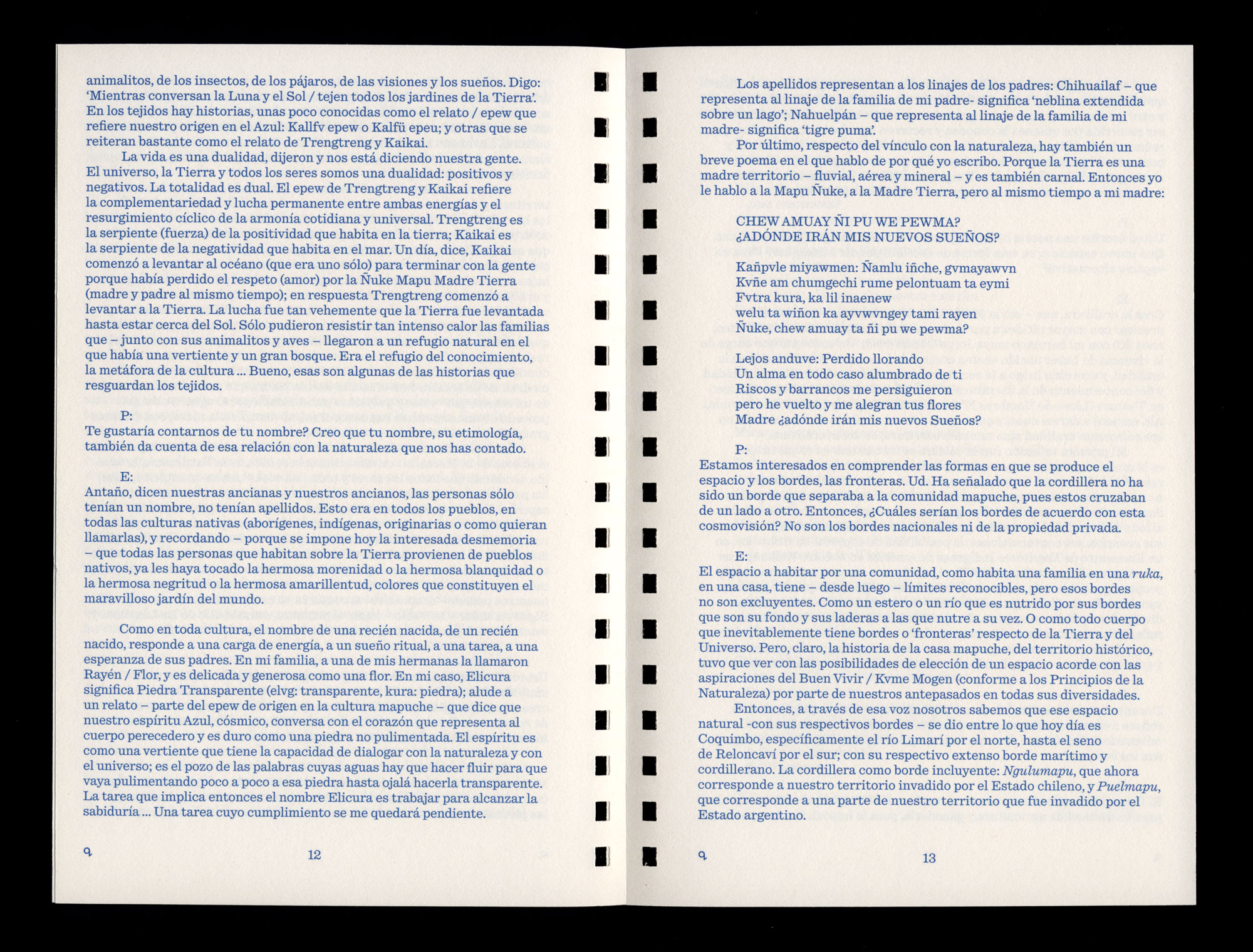

Mire, con sus hilados las tejedoras y tejedores revelan el tejido de la vida (su conversación, su abrazo): la urdimbre de los ríos y de las estrellas, de las piedras, de los arcoiris, de las flores, de los bosques, de las nubes, de los animalitos, de los insectos, de los pájaros, de las visiones y los sueños. Digo: ‘Mientras conversan la Luna y el Sol / tejen todos los jardines de la Tierra’. En los tejidos hay historias, unas poco conocidas como el relato / epew que refiere nuestro origen en el Azul: Kallfv epew o Kalfü epeu; y otras que se reiteran bastante como el relato de Trengtreng y Kaikai.

La vida es una dualidad, dijeron y nos está diciendo nuestra gente. El universo, la Tierra y todos los seres somos una dualidad: positivos y negativos. La totalidad es dual. El epew de Trengtreng y Kaikai refiere la complementariedad y lucha permanente entre ambas energías y el resurgimiento cíclico de la armonía cotidiana y universal. Trengtreng es la serpiente (fuerza) de la positividad que habita en la tierra; Kaikai es la serpiente de la negatividad que habita en el mar. Un día, dice, Kaikai comenzó a levantar al océano (que era uno sólo) para terminar con la gente porque había perdido el respeto (amor) por la Ñuke Mapu Madre Tierra (madre y padre al mismo tiempo); en respuesta Trengtreng comenzó a levantar a la Tierra. La lucha fue tan vehemente que la Tierra fue levantada hasta estar cerca del Sol. Sólo pudieron resistir tan intenso calor las familias que – junto con sus animalitos y aves – llegaron a un refugio natural en el que había una vertiente y un gran bosque. Era el refugio del conocimiento, la metáfora de la cultura … Bueno, esas son algunas de las historias que resguardan los tejidos.

P:

Te gustaría contarnos de tu nombre? Creo que tu nombre, su etimología, también da cuenta de esa relación con la naturaleza que nos has contado.

E:

Antaño, dicen nuestras ancianas y nuestros ancianos, las personas sólo tenían un nombre, no tenían apellidos. Esto era en todos los pueblos, en todas las culturas nativas (aborígenes, indígenas, originarias o como quieran llamarlas), y recordando – porque se impone hoy la interesada desmemoria – que todas las personas que habitan sobre la Tierra provienen de pueblos nativos, ya les haya tocado la hermosa morenidad o la hermosa blanquidad o la hermosa negritud o la hermosa amarillentud, colores que constituyen el maravilloso jardín del mundo.

Como en toda cultura, el nombre de una recién nacida, de un recién nacido, responde a una carga de energía, a un sueño ritual, a una tarea, a una esperanza de sus padres. En mi familia, a una de mis hermanas la llamaron Rayén / Flor, y es delicada y generosa como una flor. En mi caso, Elicura significa Piedra Transparente (elvg: transparente, kura: piedra); alude a un relato – parte del epew de origen en la cultura mapuche – que dice que nuestro espíritu Azul, cósmico, conversa con el corazón que representa al cuerpo perecedero y es duro como una piedra no pulimentada. El espíritu es como una vertiente que tiene la capacidad de dialogar con la naturaleza y con el universo; es el pozo de las palabras cuyas aguas hay que hacer fluir para que vaya pulimentando poco a poco a esa piedra hasta ojalá hacerla transparente. La tarea que implica entonces el nombre Elicura es trabajar para alcanzar la sabiduría … Una tarea cuyo cumplimiento se me quedará pendiente.

Los apellidos representan a los linajes de los padres: Chihuailaf – que representa al linaje de la familia de mi padre- significa ‘neblina extendida sobre un lago’; Nahuelpán – que representa al linaje de la familia de mi madre- significa ‘tigre puma’.

Por último, respecto del vínculo con la naturaleza, hay también un breve poema en el que hablo de por qué yo escribo. Porque la Tierra es una madre territorio – fluvial, aérea y mineral – y es también carnal. Entonces yo le hablo a la Mapu Ñuke, a la Madre Tierra, pero al mismo tiempo a mi madre:

CHEW AMUAY ÑI PU WE PEWMA?

¿ADÓNDE IRÁN MIS NUEVOS SUEÑOS?

Kañpvle miyawmen: Ñamlu iñche, gvmayawvn

Kvñe am chumgechi rume pelontuam ta eymi

Fvtra kura, ka lil inaenew

welu ta wiñon ka ayvwvngey tami rayen

Ñuke, chew amuay ta ñi pu we pewma?

Lejos anduve: Perdido llorando

Un alma en todo caso alumbrado de ti

Riscos y barrancos me persiguieron

pero he vuelto y me alegran tus flores

Madre ¿adónde irán mis nuevos Sueños?

P:

Estamos interesados en comprender las formas en que se produce el espacio y los bordes, las fronteras. Ud. Ha señalado que la cordillera no ha sido un borde que separaba a la comunidad mapuche, pues estos cruzaban de un lado a otro. Entonces, ¿Cuáles serían los bordes de acuerdo con esta cosmovisión? No son los bordes nacionales ni de la propiedad privada.

E:

El espacio a habitar por una comunidad, como habita una familia en una ruka, en una casa, tiene – desde luego – límites reconocibles, pero esos bordes no son excluyentes. Como un estero o un río que es nutrido por sus bordes que son su fondo y sus laderas a las que nutre a su vez. O como todo cuerpo que inevitablemente tiene bordes o ‘fronteras’ respecto de la Tierra y del Universo. Pero, claro, la historia de la casa mapuche, del territorio histórico, tuvo que ver con las posibilidades de elección de un espacio acorde con las aspiraciones del Buen Vivir / Kvme Mogen (conforme a los Principios de la Naturaleza) por parte de nuestros antepasados en todas sus diversidades.

Entonces, a través de esa voz nosotros sabemos que ese espacio natural -con sus respectivos bordes – se dio entre lo que hoy día es Coquimbo, específicamente el río Limarí por el norte, hasta el seno de Reloncaví por el sur; con su respectivo extenso borde marítimo y cordillerano. La cordillera como borde incluyente: Ngulumapu, que ahora corresponde a nuestro territorio invadido por el Estado chileno, y Puelmapu, que corresponde a una parte de nuestro territorio que fue invadido por el Estado argentino.

Nuestra gente en sus relatos, en su historia, nos legó la conversación que dice que nuestros antepasados transitaban por la cordillera, hacia uno y otro lado, como quien camina por esta colina. O sea, la cordillera invita a ser recorrida por quienes la conocen y recorren agradecidos; es camino que reúne a las familias mapuche -a las comunidades – que están al oriente y poniente del gran macizo natural que siempre nos acoge porque también se siente parte de la vida nuestra. Y sigue sucediendo hasta ahora, también con los animales como el puma o pájaros como cóndores y choroyes.

P:

Usted escribe una poesía bilingüe, poemas en mapudungun y en castellano. Qué nuevo espacio crea esta forma de escribir, pensar e imaginar? Crea un espacio alternativo?

E:

Crea la oralitura, que – sin la pretensión de neologismo – comienzo a precisar con mayor nitidez a partir de una conversación (Tlaxcala, México, años 90) con mi hermano maya Jorge Cocom-Pech. Un concepto que surge de la vivencia de haber nacido en una comunidad, de haber crecido aquí, en la oralidad, y accedido luego a la escritura; de la vivencia del exilio en la ciudad y del conocimiento de la literatura en las aulas de un internado en un Liceo en Temuco (Liceo de Hombres N° 1 en ese tiempo y hoy Liceo Pablo Neruda). Allí empecé a darme cuenta que – para mí – el zumbido de las palabras no era solamente oralidad sino también escritura, es decir, oralitura.

Mi primera reflexión fue: la palabra es un caminar en el que un pie es la oralidad y el otro es la escritura; cada quien siente pertenencia – o más afinidad – en uno u otro …, pero yo me siento habitante de un espacio no nombrado – aparentemente vacío – entre ambos, un espacio que podría llamarse Oralitura, me dije. Mi propuesta entonces fue: oralitura es escribir al lado de la oralidad de nuestra gente, de su memoria; sus cantos, sus relatos, sus consejos, sus conversaciones; la posibilidad de expresar su ritmo. Así, en un Encuentro de Escritores Indígenas de América en nuestro Wallmapu, en uno de sus talleres en Cunco (1997), el pueblo más cercano a mi comunidad, propuse que el tema de conversación fuera la oralitura. Mi querido hermano yanakuna Fredy Chikangana (Colombia) sería después el más entusiasta divulgador de dicho concepto … En el transcurso de los años he intentado reflexionar algo más: la oralitura es también un cauce – el agua de las palabras – cuyo lecho es la memoria que conversa con sus laderas por las que es nutrido y que nutre a su vez, cumpliendo así con el principio natural de la reciprocidad.

P:

Durante la colonización del sur se quemaron muchos bosques. Usted se refiere a esos incendios en su poesía. Qué acontecía en estos bosques milenarios? Qué fuente de conocimiento y vida portan? Qué tipo de espacio son los bosques?

E:

El fuego de los colonizadores que arrasaba a los bosques para abrir espacios para su desmedida agricultura y ganadería, para la imposición -por parte de los Estados chileno y argentino – de un desarrollo contra la Naturaleza y no con la Naturaleza, como ocurre – increíblemente – hasta hoy … Pero mejor que hable el bosque, ¿le parece?:

Soy el bosque y este es el Azul

de mi corazón

¿escuchas su latido de agua?

Hija, hijo, hermana, hermano

¿me reconoces?

Aún vivo, porque soy la casa

de la mujer y del hombre

de los pájaros y de los animales

de las piedras y de los insectos

de los hongos y de las vertientes

En mí habita la brisa de vuestro espíritu

Entre las hojas y las raíces de mis aromas

crece la enredadera de la luz

¿Ves como florece su conversación

con las sombras?

Es el canto de mis árboles

en los que resplandecen los Sueños

de las nubes y de las mariposas

Mírame, estoy aquí porque todavía tú

no vuelves a caminar entre las estrellas

Existo para que reconozcas el misterio

del orden natural

¿Recuerdas que venimos desde el Azul

infinito?

Mira el invisible vuelo de las piedras

que te sostienen en el verdor

de nuestra Madre Tierra

¿Ves? Soy el gran bosque de la memoria

de nuestra Gente y de los Antepasados

que susurran desde mis huellas

y hacia lo venidero

Como neblina, como gotas de rocío

como caudal de lluvia, como Palabras

te ofrezco el Agua

El Aire, el aire. Tu respirar que posee

las llaves de las ventanas, de tus ojos

que anhelan contemplar

la Ternura insondable

del Universo

(El bosque de la memoria)

CONVERSATION WITH ELICURA CHIHUAILAF

This text has emerged out of a conversation that was

originally held in 2016 in Quechurehue or Kechurewe, in the context of research and collaboration within the project Fence (2017) by the artist Olaf Holzapfel, as part of Documenta 14. On the occasion of the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, Paz Guevara and Elicura Chihuailaf met again in 2019 in Madrid to edit and add to the conversation.

Translated from Spanish into English by Camila Yver

P:

We are interested in understanding the ways in which space and borders are produced. You have indicated that the mountain range has not been an edge that separated the Mapuche community, since they crossed from one side to the other. So what would be the borders according to this worldview? They are not national borders or private property.

E:

The space to be inhabited by a community, as a family lives in a ruka, in a house, has, of course, recognisable limits, but those edges are not exclusive. Like a brook or a river that is nourished by its edges – its bed and its banks – which the water nourishes them in turn. Or like every body that inevitably has borders in relationship to the Earth and the Universe. But, of course, the history of the Mapuche house, of the historical territory, had to do with the possibilities of choosing a space according to the aspirations of Good Living / Kvme Mogen (according to the Principles of Nature) by our ancestors in all its diversities.

We know for instance about this natural space – with its respective borders – between what is now Coquimbo, specifically from Limarí river in the north, to the heart of Reloncaví in the south; with its respective extensive maritime and mountain edge. The mountain range is an inclusive border: Ngulumapu, which now corresponds to our territory invaded by the Chilean State, and Puelmapu, which corresponds to a part of our territory that was invaded by the Argentinian State.

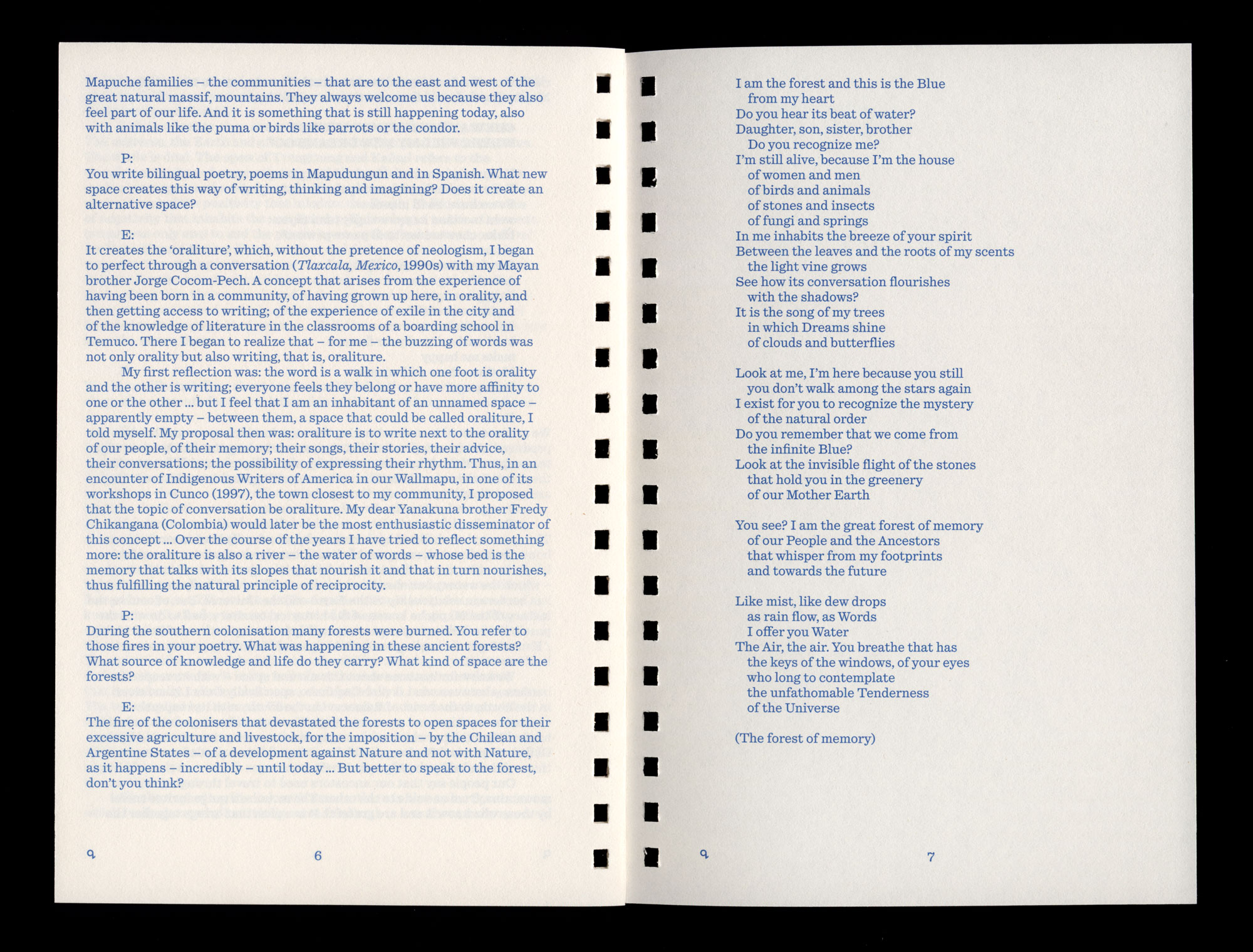

Our people say that our ancestors used to travel through the mountains, from one side to the other. The mountain range invites travel by those who know it and are grateful. It is a path that brings together the Mapuche families – the communities – that are to the east and west of the great natural massif, mountains. They always welcome us because they also feel part of our life. And it is something that is still happening today, also with animals like the puma or birds like parrots or the condor.

P:

You write bilingual poetry, poems in Mapudungun and in Spanish. What new space creates this way of writing, thinking and imagining? Does it create an alternative space?

E:

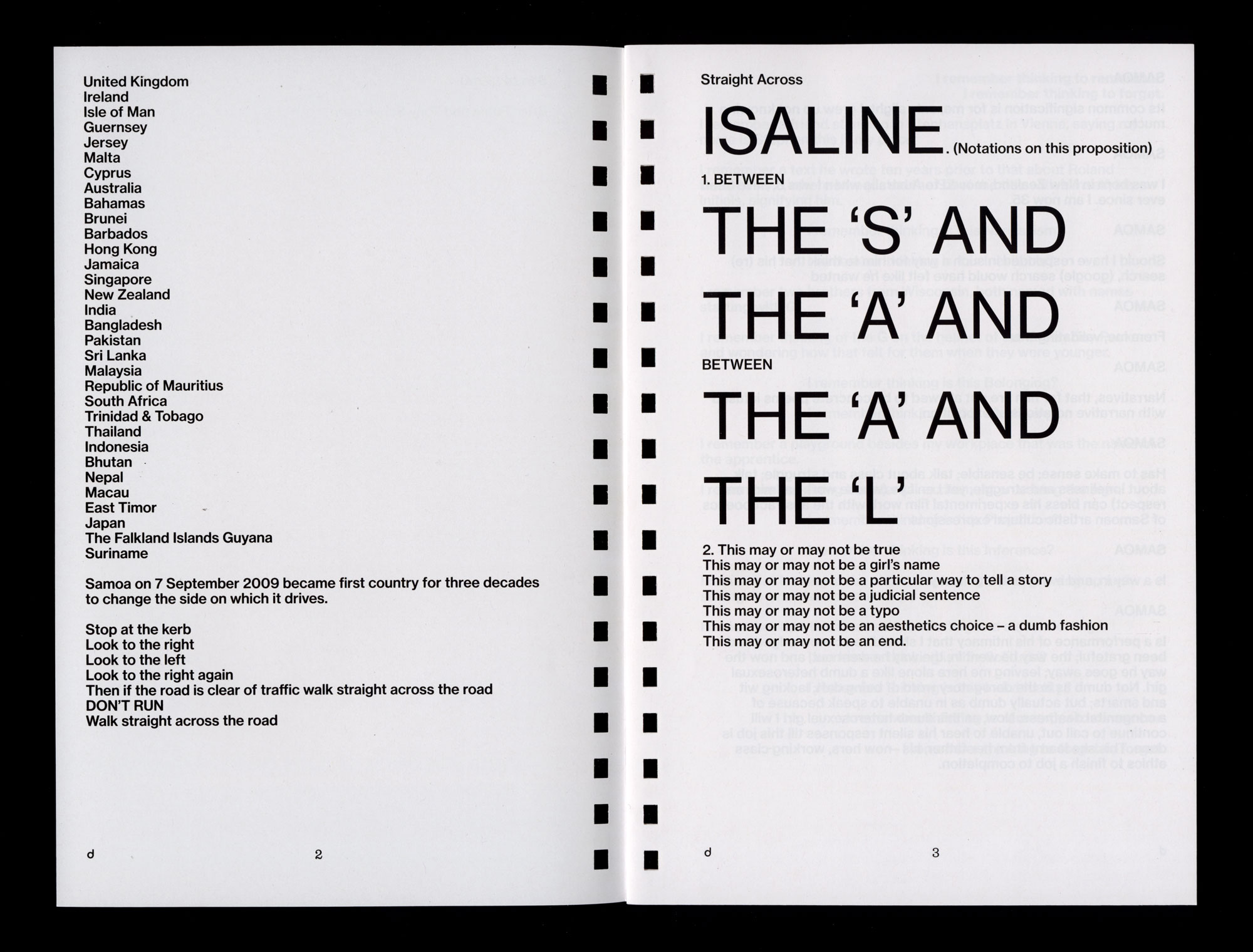

It creates the ‘oraliture’, which, without the pretence of neologism, I began to perfect through a conversation (Tlaxcala, Mexico, 1990s) with my Mayan brother Jorge Cocom-Pech. A concept that arises from the experience of having been born in a community, of having grown up here, in orality, and then getting access to writing; of the experience of exile in the city and of the knowledge of literature in the classrooms of a boarding school in Temuco. There I began to realize that – for me – the buzzing of words was not only orality but also writing, that is, oraliture.

My first reflection was: the word is a walk in which one foot is orality and the other is writing; everyone feels they belong or have more affinity to one or the other ... but I feel that I am an inhabitant of an unnamed space – apparently empty – between them, a space that could be called oraliture, I told myself. My proposal then was: oraliture is to write next to the orality of our people, of their memory; their songs, their stories, their advice, their conversations; the possibility of expressing their rhythm. Thus, in an encounter of Indigenous Writers of America in our Wallmapu, in one of its workshops in Cunco (1997), the town closest to my community, I proposed that the topic of conversation be oraliture. My dear Yanakuna brother Fredy Chikangana (Colombia) would later be the most enthusiastic disseminator of this concept ... Over the course of the years I have tried to reflect something more: the oraliture is also a river – the water of words – whose bed is the memory that talks with its slopes that nourish it and that in turn nourishes, thus fulfilling the natural principle of reciprocity.

P:

During the southern colonisation many forests were burned. You refer to those fires in your poetry. What was happening in these ancient forests? What source of knowledge and life do they carry? What kind of space are the forests?

E:

The fire of the colonisers that devastated the forests to open spaces for their excessive agriculture and livestock, for the imposition – by the Chilean and Argentine States – of a development against Nature and not with Nature, as it happens – incredibly – until today ... But better to speak to the forest, don’t you think?

I am the forest and this is the Blue

from my heart

Do you hear its beat of water?

Daughter, son, sister, brother

Do you recognize me?

I’m still alive, because I’m the house

of women and men

of birds and animals

of stones and insects

of fungi and springs

In me inhabits the breeze of your spirit

Between the leaves and the roots of my scents

the light vine grows

See how its conversation flourishes

with the shadows?

It is the song of my trees

in which Dreams shine

of clouds and butterflies

Look at me, I’m here because you still

you don’t walk among the stars again

I exist for you to recognize the mystery

of the natural order

Do you remember that we come from

the infinite Blue?

Look at the invisible flight of the stones

that hold you in the greenery

of our Mother Earth

You see? I am the great forest of memory

of our People and the Ancestors

that whisper from my footprints

and towards the future

Like mist, like dew drops

as rain flow, as Words

I offer you Water

The Air, the air. You breathe that has

the keys of the windows, of your eyes

who long to contemplate

the unfathomable Tenderness

of the Universe

(The forest of memory)

Paz Guevera (P):

You talk about a world that is not human-centred. As you have written: ‘the stories of trees and stones that dialogue with each other, with animals and with people’ (Sueño Azul, 1995) and ‘The stones have a spirit, says our People / that’s why we must not forget to Talk with them’ (Sueños de Luna Azul, 2008). For example, what stories do stones or trees tell to understand this worldview that is not centred on the human being?

Elicura Chihuailaf (E):

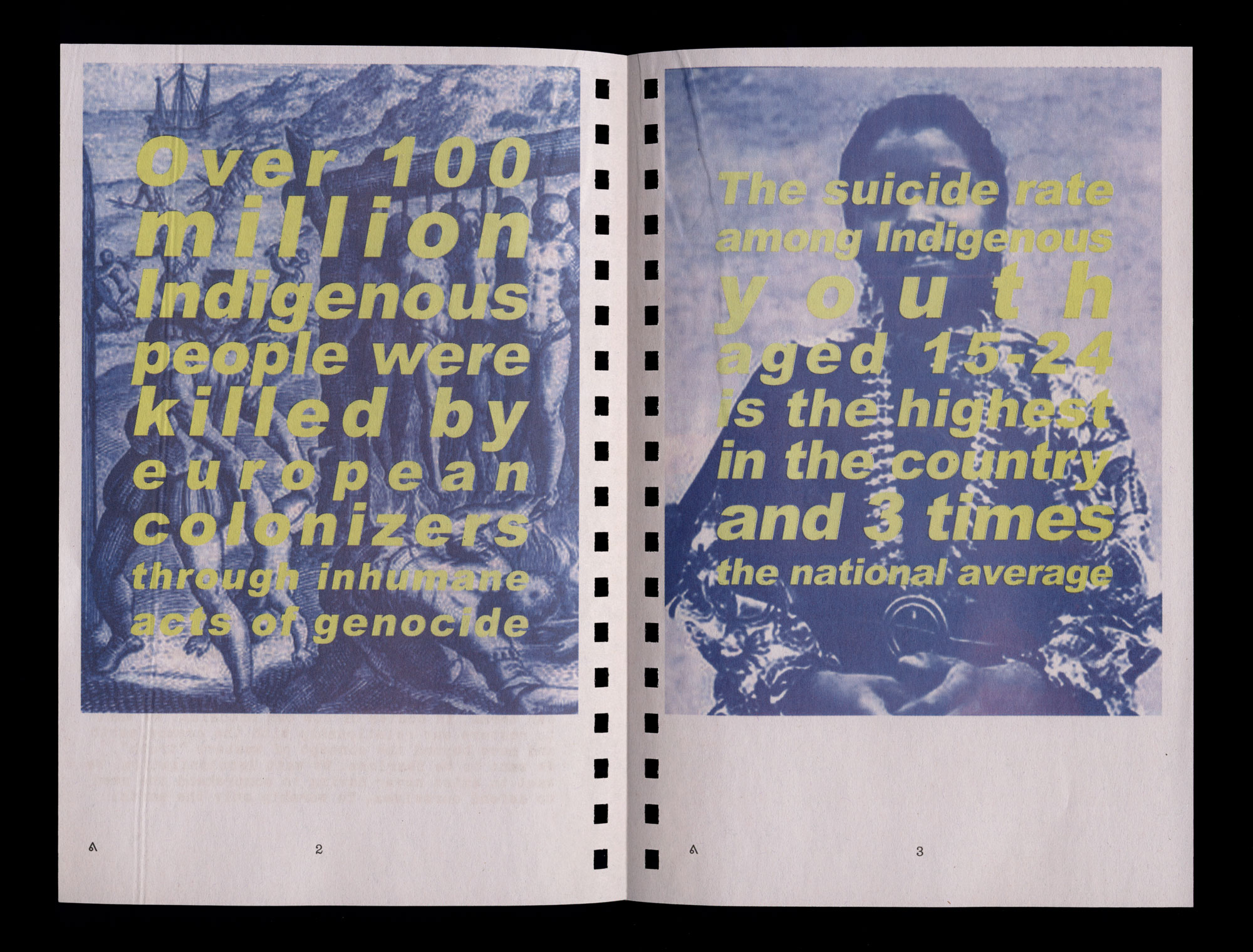

I reply by referring to the point from which this idea arises. There is a concept in Mapuzugun or Mapudungun called ‘Itrofill mogen’ or ‘Itrofilmongen’ that means ‘biodiversity’. If we describe this concept, it means the totality without exclusion, the integrity of all living things without fragmentation of life. It is the fundamental concept of the Mapuche worldview.

A human being, a living being, a stone – apparently inanimate – belongs to a place and has a ngen / a spirit. This ngen belongs to a space as much as the human being does, and as they both share it there is therefore a relationship of reciprocity, of interdependence. Hence the totality without exclusion and without fragmentation.

It is in that perspective that our people say that nobody chooses to be born with a certain colour or physical form, in a language, in a worldview, in a history, in a certain territory, but we all have, we are told, a Task: to know what has been given to us, and therefore, to know the physical space of living beings and of all those who are located in the same territory with their corresponding infinity. In Mapuzugun it is called Tuwvn, which is the physical space in which the family lives. Kvpan, which corresponds to the family / rukañma of each person. Kvpalme has to do with the community / lof of which the family is a member; the human and living environment, the totality that belongs to that community. The binding ritual of all this is the conversation / nvtramkan which is essential when you want to know something. Knowing is, they say, the only possibility of loving what has been given to us and, therefore, of reaching tenderness for ourselves.

If we love ourselves, we can understand that diversity is extraordinarily valuable and that it is essential to listen to the conversations of people, of the Earth (nature), of the universe that we inhabit and inhabits within ourselves. This means always taking into account the circle of memory (which is present because it is past and future at the same time): silence, contemplation, and creation. The conversation is creation that is sustained in the voices – the thought – of the ancestors who speak because they live in us. Conversation is an art in which the most difficult thing is not to learn to weave our thoughts; the most difficult is to learn how to listen.

We should listen – they are telling us – to the conversation of the trees, and not only what they communicate to us, but also their dialogue with other trees, to also understand how they relate to each other (the daily life of the forest). When, for example, the wind blows, not all trees move in the same way. Here, in this area of Cunco and Lake Kolico, the puelche wind is frequent. Puelche means: people who come from the east; and the puelche wind comes from the Andes mountain range, and when it blows the treetops oscillate like heads of people walking. As we know, the human walking action has similar characteristics but each one has a particular cadence, influenced even by cultural belonging. The same happens with tree families: coigües, hualles, oaks, poplars, etc. ... when moved by the wind each also has their own cadence.

Then, the trees and the forest are also telling us about the territory and the history where they belong; of the air, the water and the climate that has surrounded them. Because, of course, it is not the same to live in the foothills of the pre-mountain range of Kechurewe as to inhabit the summits of the mountains close to our territory. If, for example, we observe the leaves of the native trees here we will see that in most species the leaves are wide and concave, that is, they are prepared to receive water and abundant dew in almost all seasons ... In our community snow falls during the winter, but not as in the high mountain range where it is very frequent, so there the leaves are flat and sharp, which allows the snow to drain easily and also helps the trees to better resist the force of the constant wind. Thus, a leaf tells us where it comes from, where it belongs … Therefore, if we look at the stones, the conversation of a pebble that comes from a stream, that we see and feel polished by water, is not the same as the conversation of another stone that comes from a surface exposed to the sun, wind or snow, with varying degrees of porosity, waves and roughness.

Human beings have been losing the ability to understand the language of the Earth, the conversation of the spirit of Nature; we have been forgetting that all beings and all things have a spirit, and that words also resonate in time and watch and dream in our spirit. Everything we learn and talk about has to do with the everyday and at the same time with the transcendent and infinite, because our spirit – our grandparents and our parents told us – comes from the East, where the Moon and Sun rise. It comes from the most pristine Blue, not any blue. That is the energy that comes to inhabit its transient house that is our body, and that – just as during childhood we inhabit the house of our parents – then continues its path in the circle of life. It follows its walk – its flight – to the West; it crosses the River of Tears and returns to its place of origin, to the mystery of the deep and infinite Blue.

P:

You have written that memory can be stored in the symbols weaved in fabrics: ‘The content of the drawings that spoke of the creation and resurgence of the Mapuche world of protective forces, volcanoes of flowers and birds’ (Blue Dream, 1995). What symbols can we interpret in the textiles where memory is stored?

E:

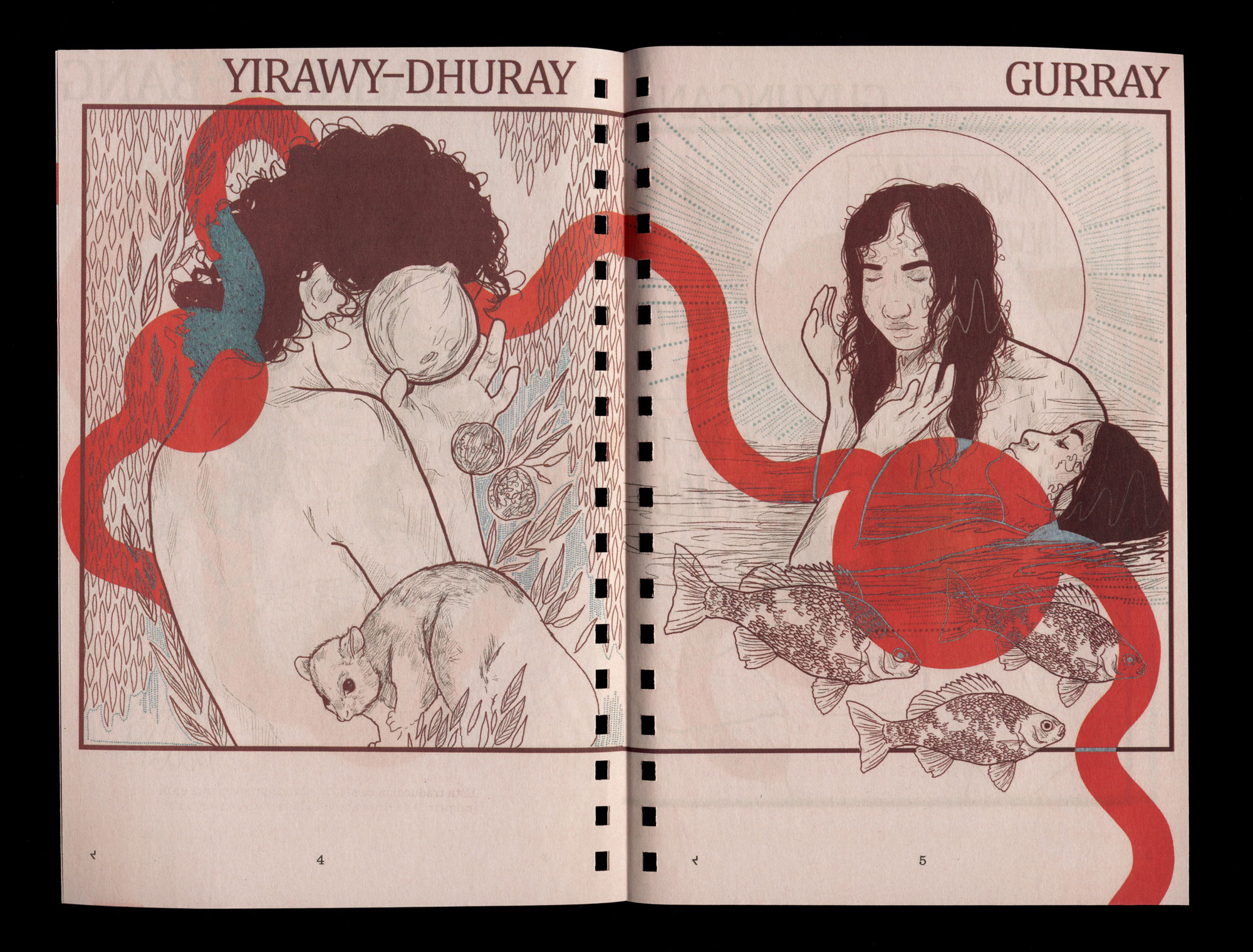

Look, with their yarns the weavers reveal the fabric of life (their conversation, their embrace): the warp of the rivers and the stars, the stones, the rainbows, the flowers, the forests, clouds, animals, insects, birds, visions and dreams. I say: ‘While the Moon and the Sun talk they weave all the gardens on Earth’. In the textiles there are stories, some little known as the story / epew that refers to our origin in the Blue: Kallfv epew or Kalfü epeu; and others that are often repeated like the story of Trengtreng and Kaikai.

Life is a duality, they use to say and our people are telling us now. The universe, the Earth and all beings are a duality: positive and negative. The whole is dual. The epew of Trengtreng and Kaikai refers to the complementarity and permanent struggle between both energies and the cyclical resurgence of everyday and universal harmony. Trengtreng is the snake (force) of the positivity that inhabits the Earth; Kaikai is the snake of negativity that inhabits the sea. One day, Kaikai began to raise the ocean (which was only one) to end the people because they had lost respect (love) for Ñuke Mapu / Mother Earth (mother and father at the same time); in response Trengtreng began to raise the Earth. The fight was so vehement that the Earth was raised until it was close to the Sun. Only the families that – along with their animals and birds – reached a natural refuge where there was a watershed and a large forest could resist. It was the refuge of knowledge, the metaphor of culture ... Well, those are some of the stories that keep the woven tissues.

P:

Would you like to tell us about your name? I think that your name, its etym-ology, also accounts for that relationship with nature that you have told us.

E:

In the past, our old men and women say, people had only one name, they had no last name. This was for all people, in all the native cultures (Aboriginal, Indigenous, native or whatever they want to call them), and we should remember – because today oblivion is imposed – that everybody who inhabits the Earth comes from native peoples, whether they belong to the beautiful darkness or the beautiful whiteness or the beautiful yellowness, colours that constitute the wonderful garden of the world.

As in every culture, the name of a newborn, responds to a load of energy, a ritual dream, a task, a hope of their parents. In my family, one of my sisters was called Rayén / Flor, and she is delicate and generous like a flower. In my case, Elicura means Transparent Stone (elvg: transparent, kura: stone); it alludes to a story – part of the epew of origin in the Mapuche culture – that says that our cosmic Blue spirit converses with the heart that represents the perishable body and is hard as an unpolished stone. The spirit is like a watershed that has the ability to dialogue with nature and with the universe; it is the well of words whose waters must flow so that it gradually polishes that stone until hopefully it becomes transparent. The task implied by the name Elicura is to work to achieve wisdom ... The fulfilment of this task will remain pending.

The last names represent the lineages of the parents: Chihuailaf – which represents the lineage of my father’s family – means ‘mist spread over a lake’. Nahuelpán – which represents the lineage of my mother’s family – means ‘tiger puma’.

Finally, regarding the link with nature, there is also a short poem in which I talk about why I write. Because the Earth is a mother territory – river, air and mineral – and is also carnal. Then I speak to Mapu Ñuke, to Mother Earth, but at the same time to my mother:

CHEW AMUAY ÑI PU WE PEWMA?

WHERE WILL MY NEW DREAMS GO?

Kañpvle miyawmen: Ñamlu iñche, gvmayawvn

Kvñe am chumgechi rume pelontuam ta eymi

Fvtra kura, ka lil inaenew

welu ta wiñon ka ayvwvngey tami rayen

Ñuke, chew amuay ta ñi pu we pewma?

Far away I was: Lost, crying

A soul in any case

lit by your light

ravines and cliffs

followed me

but I am back and your flowers

make me happy

Mother, where will my new

Dreams go?